Jerry Rubin: The Countercultural Icon Who Invented Social Networking

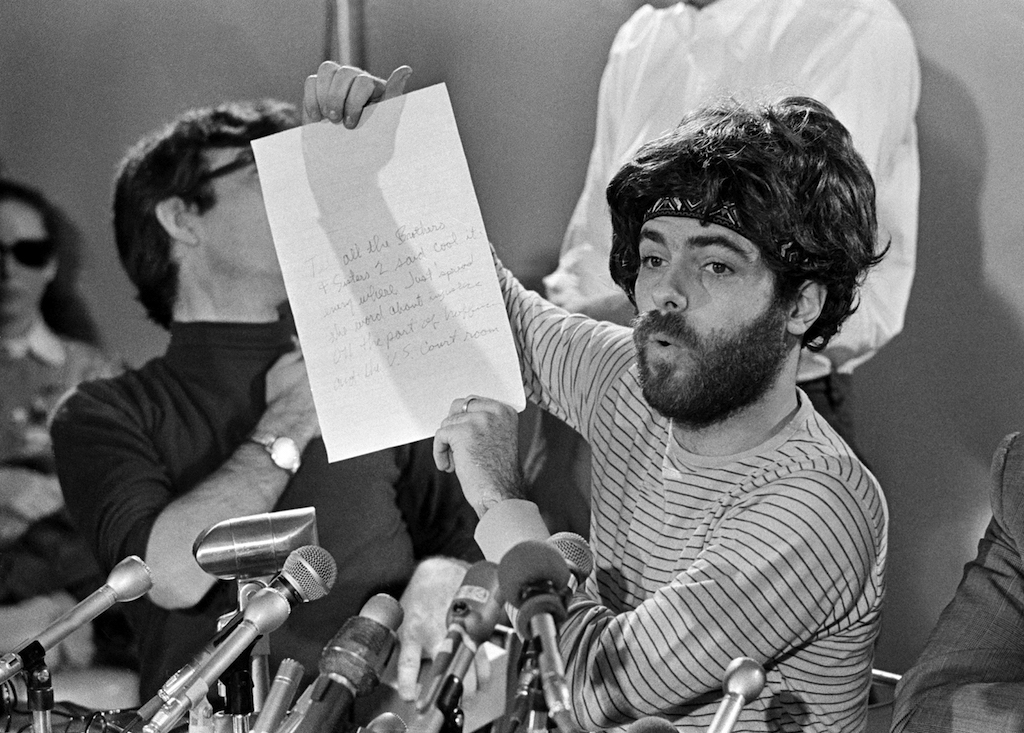

Author Pat Thomas discusses what he learned while writing a biography about the co-founder of the Youth International Party of the 1960s. Jerry Rubin, one of the defendants in the Chicago 8 conspiracy trial, at a news conference in 1969. (Jim Palmer / AP)

Jerry Rubin, one of the defendants in the Chicago 8 conspiracy trial, at a news conference in 1969. (Jim Palmer / AP)

Pat Thomas read Abbie Hoffman’s “Steal This Book” at age 10, after his 20-year-old brother brought it home. Thomas appreciated Hoffman’s humor, but years later wondered why he never heard much about Jerry Rubin, Hoffman’s co-founder of the Youth International Party, whose members called Yippees.

Rubin was known for his political theater, including “levitating” the Pentagon, dressing in a Revolutionary War costume for an appearance before a congressional committee, shutting down the New York Stock Exchange by throwing 500 dollar bills from above and organizing a Vietnam Day Teach-In on the University of California at Berkeley campus in 1965, then attended by about 30,000 students.

In the 1980s, Rubin put on a suit and tie and stopped being overtly politically involved. This made him a sellout to some. He worked on Wall Street, looking for small companies producing ecological technology, and embraced yoga, vitamins and Eastern Standard Time.

In 2012, Thomas wrote “Listen Whitey!” about the music of the Black Panther movement and got some media attention. His publisher took him to lunch one day and asked what he’d like to do next. Thomas had in mind a biography about Rubin, a paperback. But his publisher wanted a coffee table book, and that’s what Thomas has written, while staying in Rubin’s ex-wife’s pool house in Los Angeles and going through Rubin’s papers. He also traveled the country to interview 75 people who knew Rubin (including many women who are often left out of the histories of the ’60s) to write “Did It! From Yippie to Yuppie: Jerry Rubin, an American Revolutionary.”

In Oakland, Calif., where Thomas was recently doing some readings for his book, he talked about how Rubin was willing to go beyond complaining, what protesters today owe to his flamboyant style, and how Rubin was doing social networking years before Facebook.

Emily Wilson: You said you read Abbie Hoffman’s “Steal This Book” when you were 10, and thought it was hilarious. When did you start getting interested in Rubin?

Pat Thomas: It started about 12-plus years ago, when I was just surfing the internet one night and found Abbie Hoffman tribute websites. I knew there were three or four Abbie biographies out there because I’d read most of them, but I started Googling Jerry, and except for a Wikipedia entry, there was no “We remember Jerry” or that kind of thing. I started to feel at that moment that Jerry was kind of the underdog. Fast-forward five years, and I’m at Evergreen State College and a professor pulled me inside and asked if I wanted to stay home for a semester and do a project. I said I wanted to do little bio of Jerry. That was all secondary sources, and I put together a 30,000-word bio, and it became the template for the real Jerry book.

EW: What did you think when you first heard about him? Did you think he was a sellout?

PT: If I talk to anybody who grew up in the ’60s, it was always, “Jerry was a sellout,” or “Abbie was funnier,” which arguably he was. But the seeds of this, now that I think about it, go back to the ’90s, when I was in my mid-30s, and I decided to read Jerry’s book, “Growing Up at Thirty-Seven.” That book is a little bit of an autobiography, and it’s also a little bit of a self-help book. In my 30s, I was questioning what I wanted to do with my life, and I was suffering from a low-grade depression, so I really identified with “Growing Up at Thirty-Seven.” I think that’s when I started to respect Jerry past his Yippie years. I thought, “Wow, he had something else to offer.” It was always in the back of my mind. I just identified with the fact that he was willing to try anything once. People love to bitch. Jerry decided to stop bitching and started doing something. That’s kind of a thread through his whole life. Some people bitch about the Vietnam War—Jerry laid [sic] down on the railroad tracks. As I interviewed 75 people for this book, Jerry became very real to me—less of a historical figure and more of a human being.

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

EW: What do you think made him such a successful protester?

PT: A couple things—Jerry had background as a journalist, so he knew how to work the media. He knew an outrageous statement was more likely to grab the front page than a history of why we’re in Vietnam. He was funny and charismatic, but mainly he was plugged into the youth culture. It was the era of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, and he knew that if he used that angle, he could politicize hippies and turn them into Yippies.

EW: How do you think being at Berkeley influenced him?

PT: That was really ground zero for the anti-war movement. In my mind, it’s ground zero for the Vietnam protests and for the Black Panthers. Jerry gets politicized and the Panthers start, unbeknownst to each other, almost at the same time, and in a year, they’re connected.

EW: What was the first step in writing this book?

PT: I went down to meet Mimi Leonard, his ex-wife, because she had mentioned she had all this stuff. But she was reluctant to share it with me until she saw a copy of “Listen Whitey!” and saw I was an actual author. Once she saw that, she invited me to move in with her.

EW: Did you say yes right away?

PT: Yeah, because I was like, “This is going to be incredible.” I’d been thinking about moving to L.A., and I didn’t have anywhere else to live. I was very euphoric when she asked me to move in.

She had been renting a storage locker for 20 years, and she had it moved, so when I showed up, it had just been unloaded. I walked in to a room stacked floor to ceiling with boxes, so I was sleeping, basically, with Jerry’s stuff.

EW: Was she happy you were going to write this book?

PT: She was, because, strangely, she had had very few inquiries over the years, and she got caught up in it. She felt some guilt that she had left Jerry a few years before he died, and they had had these two young kids. She was sort of processing Jerry all over again, and she wanted a book she could hand to her children and say, “This is the dad you didn’t really get to know.”

EW: How did you feel when she handed over all his stuff? Were you excited as a writer, or was it sort of daunting?

PT: I was excited, and it wasn’t in any particular order. You could open up a box, and there could be a couple newspapers he was reading right before he died, then there could be a letter from the Weather Underground, then some cancelled checks from 1980—it was this real grab bag. When he died, they were divorced, and I think she just went through his apartment and started opening drawers and filling boxes. He had every newspaper article he’d written in the ’60s from Cincinnati, so dozens of articles about baseball games and interviews of local celebrities. And if someone sent him a letter, he kept it, whether it was a family member, a fan letter or a political letter.

EW: He’s famous for these flamboyant stunts—dressing in a Revolutionary War costume when appearing before Congress, throwing money at the Stock Exchange, and levitating the Pentagon. How do you think he influenced protest now?

PT: I think the Russian group Pussy Riot is a direct descendent of the Yippies, doing outrageous behavior, and I think the Occupy movement had origins in the social protest of the ’60s. There’s also this sort of pop culture element. Any time you see a documentary about the ’60s, you’ll hear the Beatles song, “Revolution,” and you’ll hear Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers of America” and Buffalo Springfield’s “For What it’s Worth.” The Yippies are part and parcel of that whole thing, and I think some people take that for granted. I just felt it was time, in 2017, to look back at this and see what it did mean and what did these guys really do. It’s more than just 90 seconds flashing in front of your eyes in a PBS documentary about the ’60s.

EW: In the book, you write about Rubin and social networking. Can you talk about that?

PT: Imagine pre-internet. There’s probably 5,000 recent graduates of Harvard in Manhattan, but they don’t know they’re all there, right? So when he announces that next Thursday, it’s Harvard night at Studio 54, and he’s spreading that message throughout Manhattan, 1,500 recent Harvard grads show up. They’re trading business cards: “Oh, I need a job,” “Oh, I’m looking for an apartment,” and a month later, he’ll do it with Yale grads. So that’s the birth of LinkedIn, that’s the birth of Evite and Facebook. He actually trademarked the phrase “social networking.” Jerry loved bringing people together. He did that in the ’60s, too. He brought the Panthers together with the Yippies. He introduced John Lennon to this band, Elephant’s Memory, and they made the “Woman Is the Nigger of the World” single, so he was always kind of doing that. He enjoyed that.

EW: Now that you’re done, what are you pleased with the book?

PT: Everything I’ve read about the Pentagon is sort of from a distance—no one was really there—or throwing the money on Wall Street, or even the Chicago riots. I’ve got a ton of first-person voices telling you what it was like to be there, and I think that makes a big, big difference. For example, the first sort of hippie event of the ’60s is supposedly January 1967 in Golden Gate Park, the Human Be-In, and Timothy Leary is there, Allen Ginsberg, and the Grateful Dead played, but I’ve never heard anyone describe what it was actually like to f-ing be there. So it was cool to track down the guy who founded the Mime Troupe, Ron Davis. He’s telling me what it was like to f-ing be there. It was great to go back and go a little past the same three or four paragraphs that we’ve all read and talk to people who were there.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.