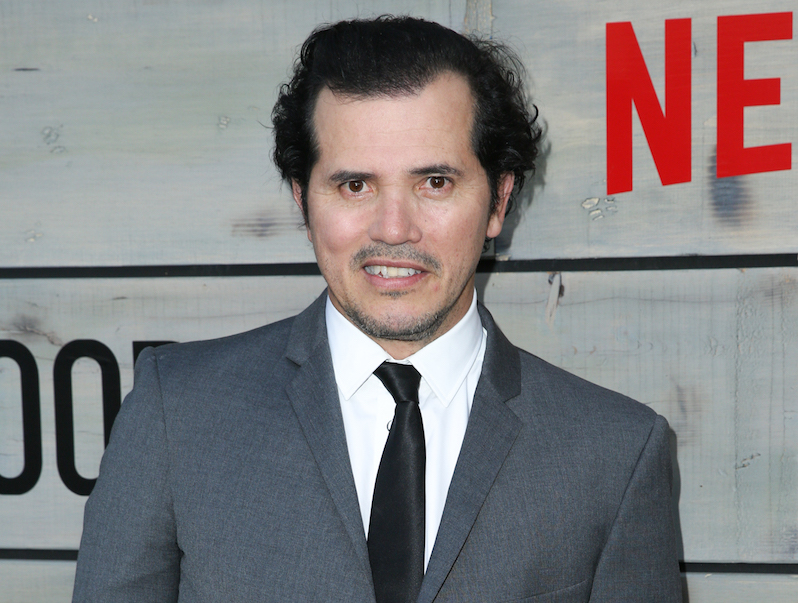

John Leguizamo Makes ‘Latino History’

The kinetic performer thought he’d sworn off solo stage shows, but a glaring failure of the American educational system has spurred him to create a hilarious new show to teach audiences the history we have been missing. Rich Fury / Invision / AP

Rich Fury / Invision / AP

Rich Fury / Invision / AP

After wrapping his 2011 solo show “Ghetto Klown,” comedian, actor and writer John Leguizamo thought he was done with the punishing routine of writing and performing material alone onstage. But now he’s been drawn in again — this time for having incorrectly answered a question his son had asked him about Native Americans. Leguizamo started doing research so his son wouldn’t catch him out again, and what he found out led to his new solo show, “Latino History for Morons,” opening Wednesday at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

Leguizamo says Latinos are mostly invisible in the American history curriculum, and because they don’t see themselves represented in the past, Latino youths are unable to project themselves into the future. “Latino History for Morons” is his attempt to educate audiences about some of their history — about the Aztecs and Mayans, for example, and about how Latinos have played key roles in building this country.

Leguizamo’s career, like his stage act, has been multifaceted. He has acted in dozens of movies, including “Carlito’s Way,” “Moulin Rouge” and “Love in the Time of Cholera,” and he has used his voice to animate Sid the Ground Sloth in the “Ice Age” film franchise. On television, he’s appeared in shows ranging from “ER” to “Bloodline” to “Dora the Explorer,” and he created the variety show “House of Buggin’ ” in the ’90s. Along with “Ghetto Klown,” which he staged on Broadway in 2011 after premiering the production at Berkeley Rep, his solo stage shows include “Mambo Mouth,” “Freak” and “Spic-O-Rama.”

Leguizamo said he started writing his own material because he wasn’t getting offered roles in Hollywood. He recently talked to Truthdig in a wide-ranging conversation that touched on a variety of subjects, including: the things he can do onstage setting that he can’t do on TV; the 19th-century French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville’s writings against the genocidal slaughter of Native Americans; and the fun he’s had acting out Aztec battles all by himself.

What did you find in your research that made you want to do this show?

I found out that 32 percent of Latin kids drop out of high school, and I started to ask myself a lot of questions. I realized a lot of it has to do with the textbooks and what we’re learning in school. When I was growing up, there was not one Latin hero in history, literature or in philosophy. I started doing research, and I was like, wait a minute — I found out that Latin people have participated in every single war this country has ever had from the American Revolution. We get no credit, and I think it’s a bit of a purposeful dis-inclusion.

You don’t think it’s people not being aware?

You look at over 20,000 Latin people who fought in the Civil War, four generals in the Revolutionary War and Cuban women in the Revolutionary War in the South selling all their jewelry and household belongings to feed the troops. The only thing I can think of is you can’t empower Latin people because then we’re going to feel entitled, and we’re going to demand what we deserve.

What did you do for research?

I tried to keep Barnes and Noble liquid (laughs.) I bought tons of books on Mayans, Incans, Aztecs, the Conquest and on all the wars. I Googled, then I bought more books from Googling, and I talked to professors.

I had been reading about the Incan, Mayan and Aztec way before, but I had to refresh my memory. There’s incredible research done on Aztecs and Incans — the Mayans not so much because they vanished before people could study them. The first ethnographer was Friar [Bernardino de] Sahagún, who annotated all the rituals and even the sexual behavior of the Aztecs. Every little detail.

How did you decide what to put in the show?

I started touring with it, and pretty quickly I realized where people [were] spacing on me or twitching in their seats, so I learned like that. People didn’t want all history either; they wanted my take on it. They wanted my personal stories that matched historic events. They really dug the Aztec stuff, and I tried to re-enact the battles because I thought that would be a lot of fun to do by myself, sort of a tribute to Jonathan Winters. I enjoyed that, so they were enjoying it. Then I was doing sort of my version of Aztec dancing and Incan dancing.

I also read some interesting people like [Alexis] de Tocqueville, this French philosopher, who spoke really eloquently against the genocide of Native Americans, and what the British and Americans were doing to Native people. It was beautifully written, and I couldn’t really do it as densely as he wrote it, so I simplified it and put it through my silly filter, you know. What did you find out that surprised you the most?

We were involved in every war this country ever had — that really bugged me out. And the numbers — 20,000 in the Civil War — that was such a huge contribution. Then 4,000 in World War I, which is kind of a small number, but 500,000 in World War II, 170,000 in Vietnam, and in no World War II movie do you see a Latin person. You never hear about it.

I read an interview from a few years ago, and you said you weren’t planning on doing another solo show because it’s so hard.

I didn’t plan on doing another solo show — I really tried not to, but I started writing, and it just wrote itself. It continues to write itself, and now I have the amazing Tony Taccone working with me, and he loved it. It was in the labs at Berkeley Rep, where I got the confidence to do it. It was such a nurturing situation, and I was working with all these great playwrights, and we were all sharing the work we were hoping to do, and they really encouraged me. It’s beautiful how artists can nurture and help other artists.

Why did you first start writing?

There were no opportunities for Latin actors, and I felt I was a talented actor, and I didn’t understand why I wasn’t getting work. My white friends would be going on five auditions a day, and I’d get one a month. And that seemed so unfair, so it motivated me to start writing my own stuff. In theater, you’re given the freedom, and there are no money restraints. There’s so many places I could go in Manhattan, and I started performing in any place that would have me, and white people loved it. It wasn’t till I did “Mambo Mouth” and got on HBO that Latin people found me, and then they became the larger part of my audience.

Why keep doing theater with all your film and TV work?

Theater is one of the more powerful forms of change. When I came on the scene, comedy on TV was very light and very cute. I came out doing stuff about child abuse, death, nervous breakdowns. The theater lets you do it — I didn’t have to go through a committee; I didn’t have to convince people. I was doing dark stuff because Latin humor is a little dark.

Look at [Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Tony award-winning Broadway hit] “Hamilton” now — you’d never see that on TV. First, we have to prove to corporations and scared CEOs that these are viable stories that people want to see, but onstage, it’s a much cheaper risk, and there’s less committee. That’s how I was able to do my much edgier, darker, psychological comedy, and that’s how “Hamilton” got to be.

What’s changed for Latinos in the performing arts?

It’s gotten a lot better. It’s not where I want it to be — we’re 17 percent of the population, and our participation in media should be as close to that as possible, but any number near there — now it’s about 4 percent. That’s better than when I was a kid — we got “Jane the Virgin,” which is amazing, we got Bobby Cannavale as the lead in “Vinyl,” you got America Ferrera, “Hamilton” on Broadway, George Lopez — there’s a ton of great Latin comics. When I’m doing the comedy scene, I’m like, there’s a lot of Latino people in the comedy scene — they’re going to be the future big comedians. When I was out there, there were no other Latin comedians, just me and maybe one other person.

What do you like the most about doing this show?

I’m really having a good time being myself. “Ghetto Klown” was really the first time I started being myself, and in this one, I’m even more comfortable being myself. I’m having a blast, and I’m really happy I was able to arrive at this place at the ripe old age of 50 [mumbles] years.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.