Kissinger and the CIA in Chile: An Interview With Peter Kornbluh, Part I

A comprehensive review of the U.S. role in the 1973 coup of Salvador Allende and its aftermath. Henry Kissinger and General Augusto Pinochet in 1973.

This is Part of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

Henry Kissinger and General Augusto Pinochet in 1973.

This is Part of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

This is part one of a two-part interview between Marc Cooper and Peter Kornbluh.

Soup and sandwich. Horse and carriage. And in the popular imagination, the Central Intelligence Agency and the Pinochet coup in Chile. A natural — and not incorrect — association. The role of the Nixon administration, led by Henry Kissinger and the CIA, in the destabilization and eventual overthrow of the Chilean government of socialist president Salvador Allende has been well known, especially since the now-iconic Senate hearings of the mid-1970s.

But many of the details remain elusive, deceptive and sometimes contradictory. Just how strategic was the CIA in its targeting of Chile? Would the coup have happened anyway? And what about Kissinger, who recently turned 100 years old and is living in freedom? Did he greenlight the killings in Chile? Did he play a role in the car bombing of dissident exile Orlando Letelier in Washington, D.C. in 1976? And once Pinochet was in power, how did the U.S. and the CIA deal with him? Did the Reagan administration play a role in removing Augusto Pinochet from power?

The answers to these and other pressing questions about Chile are addressed directly in what is arguably the definitive interview on this subject — and with the authority on the subject: Peter Kornbluh, who has worked as a researcher at the nonprofit National Security Archives since 1986. He has compiled and analyzed many of the once-classified U.S. documents that tell the complete and sordid story. He also played a key role in getting many of those documents declassified.

To call him the reigning master historian of the U.S. role in Chilean politics during the Pinochet era is hardly an overstatement. Kornbluh published his work in “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability,” the second edition of which was published in 2013. A new Spanish edition of the book is being published in Chile for the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup. Additionally, Chilean television is currently producing a four-part documentary on Kornbluh and his invaluable work in unearthing this brutal and bloody chapter of hemispheric history. Kornbluh was gracious with his time when we met together in Santiago in early 2023.

This is the definitive interview on the CIA and Chile.

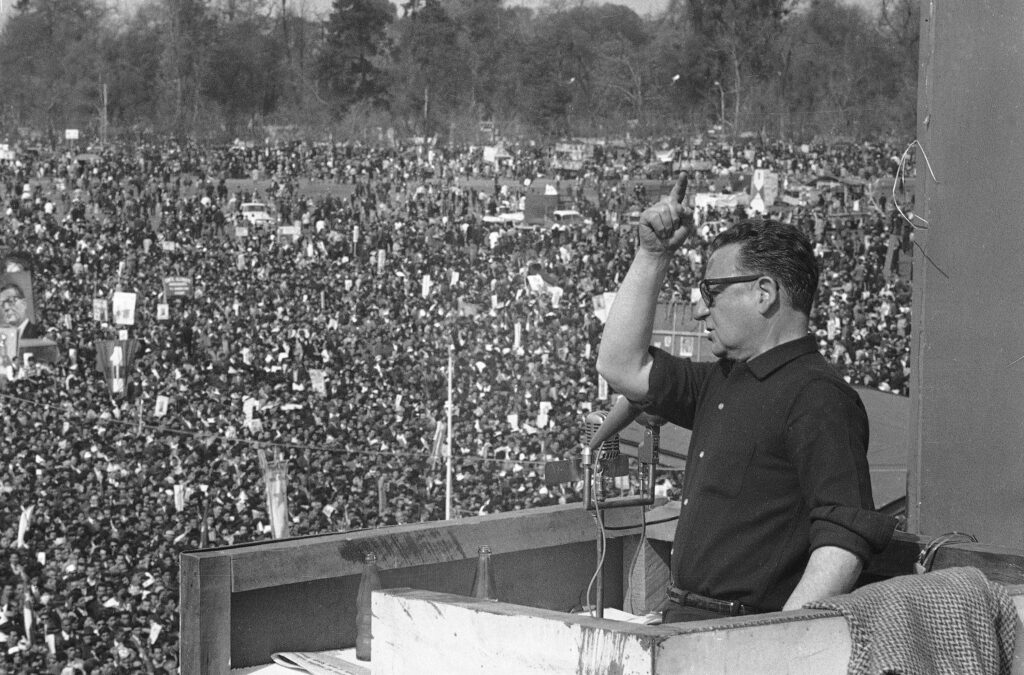

Marc Cooper: When we think of the relationship between the CIA and Chile, the tendency is to begin in 1970 with the election of Salvador Allende, a Marxist, as president of Chile. Nobody has put together a more comprehensive look at the role of the United States in Chilean politics during the Pinochet era than Peter Kornbluh. With that hat on, Peter, would you agree that 1970 is not the best place to start?

Peter Kornbluh: We need to go back to 1958 to a three-way presidential race between Allende, the oligarchical candidate, Jorge Alessandri, and the Christian Democratic candidate Eduardo Frei . At that time, Salvador Allende was a politician, a well-regarded doctor, a leader of the Chilean Socialist Party. Actually, he was a perennial candidate. When he won the presidency in 1970, it was the fourth time he ran. And in 1958, he came extremely close. If not for the presence of a popular, progressive, priest who got about 4 or 5% of the vote running as an independent, Allende would’ve likely been the first freely elected Marxist president in the world — at the height of the Cold War in the late 1950s. And world history would have been different because he would have created a model for social and political change in Latin America — one year before Fidel Castro took power in Cuba.

MC: Instead, Castro took power through armed revolution and scared U.S. policymakers, who increased their focus on thwarting any revolutionary change in Latin America. And this was at the time of the transition from Eisenhower to Kennedy.

PK: Kennedy won, but he pursued an interesting Cold War policy toward Chile. He wanted Chile to become the alternative model for reform to Castro’s model of armed revolution, which the United States saw as pro-Communist and threatening. Under Kennedy, the Alliance for Progress, a 10-year plan to foster economic cooperation between North and South America as a bulwark against the influence of the Castro regime, poured money into Chile to support a middle-class centrist party: the Christian Democrats, led by Eduardo Frei. In 1962, Frei came to Washington for a secret meeting with Kennedy and got anointed as the chicken that was going to lay the golden egg for Latin America’s reformist revolution. The U.S. would finally abandon the oligarchical forces, particularly in South America. They didn’t do that in Central America.

Some Chilean historians refer to the 1964 CIA propaganda push in Chile as the “Campaign of Terror.”

And because they understood that if they continued to support the extreme right and the rich, they were going to lose the masses to the allure of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and others. So they poured money into the program of the Christian Democrats, and the CIA came into Chile with Kennedy’s authorization and started funding the Christian Democrats in 1963 for the ’64 election. There is a whole case history of the CIA’s operation in 1964. They were so proud of it that they wrote a whole case history.

MC: I’ve never seen that.

PK: That’s because more than 50 years later, it’s still top secret. We haven’t even read it, but we know from other reports that have come out of what the CIA did, including that the agency funded more than 50% of Frei’s 1964 Christian Democratic campaign, including the rent on all the headquarters and offices. The CIA also bought up the radio stations, passing money to key operatives in the Christian Democratic Party to buy the radio stations. They bought newspapers. They bought television time and television stations — all to promote the Christian Democrats. It worked.

MC: Some Chilean historians refer to the 1964 CIA propaganda push in Chile as the “Campaign of Terror” — a truly terrifying depiction of Chile succumbing to Communism. Maybe this was the birth of fake news?

PK: Yes, a lot of disinformation, a lot of media manipulation. In 1964, the CIA had these basic scare tactics. Overnight, huge posters would appear on walls all over Santiago trying to scare the middle class. A lot was aimed at women, saying that not only the Communists but also Allende’s Socialists were going to take your children. They’re going to send them to Cuba. They’re going to send them to Russia. And it worked. Frei won by a pretty significant margin — almost 10%. And then for six years the U.S. funneled more than a billion dollars in aid and investment into Chile to try and bolster this new political model of the Christian Democrats and quite explicitly keep Allende and his coalition from gaining momentum in the future. That failed. The ’64 election succeeded in terms of the mission of U.S. operations, but the ’64 to 1970 efforts to keep the Christian Democrats afloat and popular — failed.

MC: That was, in part, because Chile was part of the bigger world in the 1960s.

PK: The 1960s — as you know, because you grew up then, and so did I — was about shaking up the world.

MC: Chile was not exempt.

PK: The Chileans had a set of basic interests. The majority of Chileans wanted agricultural reform. They wanted to see a bridge between the extremely wealthy, who owned everything, and the rest of everybody, who didn’t own anything. They wanted the countryside to be developed for the peasantry. They wanted sovereignty over their main natural resource for export — copper — which was owned by two U.S. companies, Kennecott and Anaconda, both interventionists. Also, all the utilities were basically owned by IT&T, which was a rather infamous monopolistic, imperialistic corporation. They basically defined economic imperialism.

And those companies, by the way, as the 1970 election approached, went directly to Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon and said, “We want Arturo Alessandri to be the next president of Chile, and we’re going to start funneling money to him, and we think you should work with us.” This is pretty interesting, these meetings where the corporations come in and say, “You’re not coming to us to ask us to work with you. We want you to work with us.”

MC: Think about it. ITT, Anaconda and Kennecott: The awesome power of monopolies.

PK: And it’s very interesting. Kissinger would later tell Nixon, “I turned them away. I turned them away.” The U.S. government was not that keen on the ultra-conservative Alessandri winning, but the intelligence indicated that he would win. And the corporations didn’t want to take any risks. So they funneled money to Alessandri to Swiss and Argentine bank accounts.

MC: This is the run-up to the 1970 election.

PK: Right. And the history of full-fledged efforts to undermine Allende in many ways starts in the summer of 1970 as the Sept. 4 election is approaching. But U.S. agencies, the State Department, the CIA and the White House, are all in disagreement about what operations to run. Should we directly intervene and fund the Christian Democrats? Should we run a discrediting operation against Allende? Should we start talking to the Chilean military about a coup? And since there wasn’t really any consensus about who was going to win — Alessandri or Allende — they adopted, in the end, the CIA’s plan with Nixon and Kissinger’s blessing. But they deeply feared any public revelations about their role, which would of course help Allende.

This was all top secret. But at the same time, they wanted to do something. So they began to reach out to some Chilean congressmen about what would happen if Allende was elected, won the plurality but not the majority, and then the Chilean congressmen had to ratify him two months later. How could that be manipulated? They reached out to Frei about contingency plans. It was similar to what happened when Trump was threatening a coup in the United States: the Chilean military understood that they were going to be the deciding factor. And preemptively before the Sept. 4 election, the commander-in-chief of the Chilean Army , Gen. Rene Schneider — the Chilean equivalent of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the United States of America — said, “The Chilean military will not be intervening in the results of this election. We are a constitutionalist force and we will respect the will of the Chilean people.” So he was attempting to take his military forces off the table as an actor. [Editor’s note: Chilean presidents are elected by direct popular vote. If no candidate wins an outright majority, Congress chooses the winner. Allende won the first plurality of 35% and was ratified by a congressional majority after he made constitutional guarantees to the Christian Democrats.]

MC: With Allende needing only a plurality and with three major candidates running again in 1970, the Nixon administration must have been quite anxious.

PK: Two things happened. One, a declassified document shows, is that the issue of fomenting a coup (if Allende won a plurality) had to be considered as a contingency plan. And that first issue started to go around secretly to various high-level officials in August of 1970, before the election. The other is that, as the election approached, the CIA conducted a discrediting operation — basically a black propaganda campaign. And one U.S. official said they basically pulled out all the black propaganda posters that they had in 1964, changed the dates and slapped them up on the walls again. And of course, there was black propaganda against Allende in the newspapers that the CIA controlled.

It was in the leading major establishment daily in Chile, El Mercurio — yes, we would call it fake news today. The CIA was very adept at disinformation campaigns. That was all happening in the lead-up to the Sept. 4 election. And then on Sept. 4, Allende actually won by 36,000 votes. That’s not a lot of votes, particularly for the first freely elected Marxist president of a democratic country. He did not have a majority. He had a plurality. Now, I should point out, a lot of people say, “Well, that’s not very many votes.” And I should point out that if George Bush won in 2000 at all, it was by 500 votes. There are elections that are decided by a lot fewer than that.

MC: Allende had roughly a third of the vote, but I would argue that had to be understood in a context in which another third of the vote was much closer to the ideas of reform, closer to an Allende than they were to the oligarchs at that moment. The Christian Democratic nominee, Rodomiro Tomic, had moved far to the left and had adopted a program very similar to Allende’s. So it was actually much more than one-third of the electorate that wanted deep reform.

PK: Sure. The Christian Democrats had been forced to the left to try and pick off Allende voters. They had taken a much more radical position on nationalizing copper and on agricultural reform. And so yes, the majority of Chileans were voting for significant change. The Christian Democratic candidate came in third, but the vote was the vote. And as Kissinger would later put it in a memo to Richard Nixon, and I’m paraphrasing, “Allende was elected legitimately, and there’s nothing we can say or do to de-legitimize the fact that he was democratically elected. So how are we going to deal with this guy?”

Thousands of declassified documents, including CIA operational records on covert operations to foment a coup in Chile, became available to the general public.

So Allende is elected and a whole series of events break out as he still has to be confirmed by the Chilean Congress and the inauguration is still two months away. And one of the beauties of getting the documents declassified is that we can literally chart now — day by day, hour by hour, minute by minute — what happened in each of the U.S. offices — from the White House in Washington to the CIA station in Santiago, Chile — how the United States policymakers and operatives responded to this. And it’s an extraordinary story. Students of the history of U.S. intervention in Latin America are lucky because the public eventually got the documents. We eventually had revelations reported in The New York Times thanks to the pioneering 1975 Senate investigation into CIA covert intervention around the world, but particularly in Chile, including CIA assassination plots detailed in Chile. And eventually, years later, thousands of declassified documents, including CIA operational records on covert operations to foment a coup in Chile, became available to the general public.

MC: Take us now into that volatile two-month period between Sept. 4, 1970, when Allende is voted in as president, and Oct. 24, the day when a majority of Congress had to go with him or choose another.

PK: That’s right. He will need the votes in Congress to be ratified as president and then inaugurated two weeks or so later. And this period of time, two months, somehow in the minds of imperialist U.S. policymakers is, “Oh, we have this opportunity to somehow block him, to somehow create a ’coup climate’ in Chile.” How does this all evolve? Within hours of Allende’s election, Agustín Edwards — one of the richest men in Chile, goes to talk to Edward Korry, the U.S. ambassador. Edwards was not only the owner of Chile’s leading newspaper, El Mercurio, but of a whole media empire. Edwards is the Rupert Murdoch of Chile. He’s the representative of Pepsi in Chile, and very close to the head of Pepsi, Donald Kendall. Edwards, being one of the richest guys in Chile, has the most to lose from a newly elected socialist president.

Edwards says to Korry, “What are you going to do? How are you going to stop this?” And he doesn’t get the answers that he wants. He doesn’t get the dedication like, “Oh, we have a plan already in place, don’t worry. We’re going to take care of this.” And so Edwards calls his colleague, friend, and erstwhile boss, Donald Kendall, who’s head of Pepsi, and he says, “I have to come to Washington.” And Kendall helps him by setting up a series of meetings. On Sept. 13, just nine days after the election, Edwards arrives in Washington. And less than 24 hours later, on Sept. 14, he met face-to-face with CIA Director Richard Helms…and the next morning, had breakfast with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger at the White House.

MC: Would you say that, by this point, Kissinger is already — or is poised to become — the quarterback of this operation?

PK: Two key players emerged who arguably are the fundamental two individuals to create a history of U.S. intervention in Chile and the intervention and overthrow of Allende, the advent and consolidation of one of the bloodiest military regimes in Latin American history. Agustín Edwards — a true traitor to the cause of democracy in his own country — and Henry Kissinger, the quarterback, the architect of efforts to overthrow Allende and then embrace Augusto Pinochet.

The documentary record is absolutely clear that the role of these two individuals is fundamental to the way history unfolds in those eight weeks after Allende was elected. And Edwards comes to Washington. He has the highest level meetings of any Chilean civilian or military, and sits down with CIA Director Helms, not just for chit-chat, but to pass mountains of human intelligence and analysis on who the potential coup plotters are in Chile, what power they have in their various positions politically and in the military, who the obstacles to a coup are, and where the Chilean president Eduardo Frei stands on the issue of a coup. Edwards tells Helms that Frei will fink out. He’ll chicken out at the last minute. He may tell you he supports a coup, but then he’ll get a phone call from somebody saying this is a bad idea. And he’ll turn around, do a 180 and change his mind. And the detail that he provides in this first meeting with the CIA director is astounding.

MC: A bonanza for the CIA. You might say, an eye-opener.

PK: A bonanza for the CIA. And two things happen. They gather all this intelligence and start to process it. The next day, the 15th, Nixon calls in Helms and says, “You have to block Allende from being inaugurated. Make the economy scream. Don’t tell the embassy. $10 million more if necessary. Use the best men you have.” All of this is written down in handwritten notes that became the leading iconic document in later revelations. And for a long time, many years really, it was the only document that we had on Nixon’s orders to preemptively block Allende from becoming president. And this is very important. The more modern generation of students in foreign policy history knows the expression “preemptive strike” because that’s what George Bush was doing in Iraq after 9/11. Well, Nixon siccing the CIA into Chile was a true preemptive strike because Allende hadn’t even been inaugurated yet. He hadn’t set foot in the Moneda Palace, the equivalent of the White House. He hadn’t issued a single policy directive aimed at the United States, aimed at U.S. business, nothing.

MC: Plus he had a multi decade history — not only him but his coalition — of being democratic, of being president of the Senate and, by Chilean standards, a totally mainstream politician with a 40-year record of flawless democratic activity.

PK: Moderate and democratic. He stood for nationalizing the copper industry. He wanted good relations with the United States. He understood what had happened with the breach between Castro and the United States. He wasn’t going to follow in Castro’s footsteps in just breaking relations with the United States. But he also wanted to negotiate the nationalization of Chilean copper, something that his predecessor Frei had started and that the Christian Democrats were committed to and that the Chilean public wanted. The nationalization of copper was one of the main reasons that Salvador Allende became president of Chile.

Kissinger basically put on his covert operations cap and became a pseudo co-director of the CIA in Chile.

But with this order from President Nixon, Kissinger basically put on his covert operations cap and became a pseudo co-director of the CIA in Chile. It was Kissinger who received 48 hours later the CIA’s immediate plan for blocking Allende’s inauguration and oversaw those operations in a sense. He met every few days with the top CIA representative in charge of the effort to block Allende’s inauguration. There are some incredible documents. One of them is the CIA director sending a cable to the station basically saying, “You have to develop these psychological operations. You have to start rumors. Go to a bar. Have your people plant three rumors a day for ten days in a row that the economy is tanking.”

We’re talking about the best eight or nine or 10 CIA officers here. “Go sit in the bars and start spreading rumors about how Allende’s election is going to force the Ford Motor Company to leave Chile. Oh, and by the way, go talk to the head of the Ford Motor Companies and say, ‘You should leave Chile and make a big dramatic announcement that you can’t stay here and that there’s not going to be any more cars and that everybody’s going to lose their job.’ In other words, shake it up. Make it clear that everybody’s going to lose their job.

It’s terribly interesting. The CIA station chief writes back and he says, “There’s no way we can foment a coup in eight weeks here. Chile is tranquil.” He said, “There’s no upheaval here. There’s no popular screaming about Allende’s election. Everybody knows Allende and they are okay with what’s happening here. They don’t see the situation like we do.” And the answer comes back from Langley headquarters. “We didn’t ask for your opinion. These are our orders from the president, from higher authority,” as they refer to the president and Kissinger in the documents. “And they’re not interested in your feedback or your resistance. We just have to do it.” And the plot to overthrow Allende, the plot to block Allende’s inauguration and create what the CIA routinely refers to as a coup climate in which there’s so much turmoil and upheaval, there’s a justification for the military to move, begins to center on the then-commander and chief of the Chilean Armed Forces, army Gen. René Schneider.

MC: …who had already declared that the army was not interested in politics.

PK: Just like the U.S. military leadership after Trump lost the election declared, “Hey, we’re not going to help anybody here.” Gen. Schneider understood that the military would be pulled into this political discord. And he had announced preemptively that under his leadership was a constitutionalist military and a pro-democracy military, and they were going to respect the will of the Chilean people.

MC: This brought a lot of attention to him from the CIA.

PK: It did. But I don’t think — given Chile’s history — that he really understood that there were these groups under him who were going to work with the CIA and do this. And if you read the documents carefully, you see that, in fact, even under Frei, before Allende was inaugurated, they took note that all these Americans were somehow suddenly coming to Chile. There was an influx of visa applications and then they counted the visas and they started calling in the ambassador saying, “Why are all these people suddenly coming?” So there were a lot of suspicions here, but Gen. Schneider stood in the way. If he had been pro-coup, then he would’ve been able. He would just give the order. “Let’s deal with this.”

He would’ve been a leader of a conspiracy. Instead, he was the leading obstacle to the conspiracy. So what does the CIA do? It starts to work with other extremist groups. It finds three groups. The first one has never been named. And it’s the history of meeting with this group, which I believe is Patria y Libertad, a militant Proud Boys-type crew of violent street brawlers.

It’s a neo-fascist organization that the CIA starts to meet with about getting rid of Schneider. And actually, the CIA documents show, although we don’t actually have the physical documents, that this group was too extremist for them and they stopped meeting with them. Then they start to meet with two other groups that are more fundamental. One is a group led by retired Chilean Gen. Roberto Viaux, who is known to be also on the fascist side and very pro-coup. And the other is an active duty military officer and his team, Camilo Valenzuela, who himself wants to rise up and become a higher-ranking leader.

MC: The CIA dealing with these three groups, even though one drops out — this is specifically talking about getting rid of Gen. Schneider, right? To take him off the board before the Oct. 24 congressional vote that will confirm Allende.

PK: Getting rid of or removing him are the operative words here. Now, the plan that gets developed is to kidnap him, fly him to Argentina, disappear him and blame Allende’s forces, which is an incomprehensible, arrogant idea. Who in their right mind would think that anybody would believe that Allende forces are going to take out the pro-constitutionalist commander-in-chief of the armed forces?

MC: This was going to be a true false flag operation.

PK: Yes. And, in fact, the CIA sent in four men whom they called false flaggers. Now, you have to know the game of covert operations. Many CIA agents are under diplomatic cover. They’re already in the embassy posing as the agricultural attaché or the commercial attache or political officers. That was always the giveaway. You had 10 political officers. Why do you need so many political officers? Because eight of them were actually CIA agents. And those people had diplomatic immunity and cover and all of this. And for the most part, the Chileans and other countries would figure out who those people were.

But the CIA also had two different, other kinds of groups of agents. They had false flaggers, sometimes known as NOCs — non-official commissioned agents — who don’t have any diplomatic cover, who come into the country posing as businessmen or tourists. And they sent in a team of false flaggers led by a legendary CIA deep covert operator named Anthony Sforza. Had a long history of covert warfare against Che Guevara, against the Cubans and against a lot of places. He was really a very indecent, vulgar human being. And a couple of other false flaggers, three others, all to meet with Valenzuela and others to talk about this plan. And the CIA details, the head of the U.S. military operations here, the defense attaché who knows all these military guys already — he’s buddies with them, rides horses with them, drinks with them — to also be a liaison for this covert operations plot.

A bunch of things happen to make this operation work. The CIA agrees to provide life insurance policies to Viaux and his buddies. They sent $50,000 to Camilo Valenzuela and a set of untraceable weapons.

MC: Machine guns.

PK: Yeah. They were sent in a diplomatic pouch designated, I believe, as fishing gear. Kissinger was briefed on Oct. 15 on this operation. And basically, he’s briefed about the discussions with Viaux. Now remember, Viaux is a retired general. He doesn’t command any troops. The plot, the CIA’s top people, and Kissinger evaluate that and they basically say, “We can’t let Viaux do this by himself because a preemptive coup that fails is going to be the worst thing.” So they basically decide, “No, he has to work with Valenzuela and others. So we’re going to go tell him, ‘You can’t do this by yourself and you need to work with others because otherwise, it’s going to fail.’

Now, after Schneider is murdered, Kissinger would later say, “We didn’t have anything to do with this because I turned it off. I turned it off at this meeting on Oct. 15.” But let me read to you the top secret restricted handling classified message that the CIA sends from Washington to its station minutes after coming out of the meeting with Kissinger.

MC: Where he theoretically has shut it down.

PK: Right. “Policy objectives and actions were reviewed at high U.S. government level the afternoon of the 15th of October. Conclusions which are to be your operational guide follow below. It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. It would be much preferable to have this transpire prior to the 24th of October, the day when Congress is supposed to ratify Allende. But efforts in this regard will continue vigorously beyond that date. We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end, utilizing every appropriate resource. It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the U.S. government and American hands be well hidden. While this imposes on the U.S. a high degree of selectivity in making military contacts and dictates that these contacts be made in the most secure manner, it definitely does not preclude contacts.”

Continuing. “After most careful consideration, it was determined that a Viaux coup attempt carried out by him alone with the forces now at his disposal would fail and this would be counterproductive. So we are to warn him. Our message is, ‘We have reviewed your plans based on your information and ours. We have come to the conclusion that your plans for [a] coup at this time cannot succeed. They may reduce your capabilities for the future. Preserve your assets. We will stay in touch, and [the] time will come when you together with your other friends can do something. You will continue to have our support.’ Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

And this is what came down after the meeting with Kissinger. Not that the thing is turned off, only that they don’t want this one guy to go rogue and not collaborate with the active duty military officers the CIA was now favoring. And by the way, and this is so important, the Church Committee led by then-Sen. Frank Church that investigated this later didn’t have the budget to send researchers down to Chile. And if they had, they would’ve seen the court documents after Schneider was murdered, which reveal that Viaux met with Valenzuela. And the plan is between the two of them. The active duty military officers aren’t going to get their hands dirty by being involved directly in the kidnapping. So they’re going to let Viaux do that, but his timing will dictate how they respond.

And they come up with a plan. First, they’re going to try and intercept Gen. Schneider on Oct. 19 when he’s leaving a military party in Santiago. He’s going to be kidnapped and sent to Argentina, and then the military will move. Then for whatever reason they reset the day for the 22nd of October. And everybody’s working on this together. But on the U.S. side, Kissinger basically thinks he has saved his and the CIA’s ass. After all this goes sour, they make up this story that they were really only working with Viaux and he did it on his own, and blah, blah, blah. And it’s just a completely false narrative.

MC: Because Kissinger knew that this “rogue” element was actually working with Kissinger-backed, on-duty military officers.

PK: Here’s what happens on the morning of Oct. 22, 1970. Gen. Schneider is driving to work with his chauffeur. Four cars intercept him at an intersection in Santiago only several blocks from his house, cut him off and approach his car with guns and sledgehammers. And as they start to bash in the back window, he reaches for his revolver and they machine-gunned him to death. They shoot him and he’s mortally wounded.

This is an assassination plot in which, in the end, Henry Kissinger is a functioning, if not the mastermind, authority.

Now, that’s not supposedly what the plan was supposed to be. He was supposed to be kidnapped. But do you think that the CIA then writes, “Geez, what the fuck happened here? That wasn’t the plan.” They write something completely different. Let me just read it to you.

The cable comes from CIA headquarters, from Richard Helms’ office itself to the CIA station after Schneider is shot and dying at a hospital. “We have reviewed the FUBELT” — that’s the code name for this program — “on the 23rd of October.” This is the day after Schneider is shot. He’s now dying and he dies the next day in the hospital. “It is agreed that given the short time span of FUBELT and circumstances prevailing in Chile, a maximum effort” — this is a reference to the Schneider shooting — “has been achieved. Only Chileans themselves can manage a successful coup, but the station has done [an] excellent job of guiding Chileans to [the] point today where a military solution is at least an option for them.”

MC: Astounding.

PK: “The chief of the station, the false flaggers and the other members of the station are commended for accomplishing this under extremely difficult and delicate circumstances.”

MC: The murder of the Chilean Army Commander.

PK: Yeah. This is the letter of commendation that comes down to the CIA station from headquarters after Schneider is shot and dying. And so the documentation is extraordinary. And why do I share this with you? Because this is an assassination plot in which, in the end, Henry Kissinger is a functioning, if not the mastermind, authority.

The paper trail goes all the way up to his office in terms of his responsibility and accountability. And when the documents were finally released, I brought a packet of them down to Chile myself, and I met with the son and grandson of Gen. René Schneider, and I said, “This is the evidence.” And they said, “Who can we hire as a lawyer in the United States to sue Henry Kissinger for wrongful death?” And they hired Michael Tigar and they sued Henry Kissinger for wrongful death.

And the day before the suit was filed, “60 Minutes” aired an entire segment on Kissinger and his role in the Schneider assassination. “60 Minutes” sent a team down here. They retraced Schneider’s path on the day that he was intercepted. They interviewed Edward Korry. They interviewed the guy who’d been the U.S. military attaché here and who’d met with the Chilean military about this operation. They reviewed the documents. They used the first chapter of my book, “The Pinochet File,” as a basis for their report. And that story for 48 hours had Kissinger cast in the role as basically an international assassin. And it was very, very powerful. The story was broadcast on Sunday, Sept. 9, 2001. The lawsuit was filed on Sept. 10, 2001. And news of the lawsuit appeared on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

MC: So it didn’t appear? On 9/11? The second 9/11.

PK: The world had completely and fundamentally changed that morning forever for the American public, and the whole argument over the issue of the political assassination was swept away in this horrible atrocity that took place in the United States of America, the U.S. 9/11. Chile had its 9/11 in 1973. The U.S. had its 9/11 in 2001. But I’m grateful that at least the segment aired because if it hadn’t aired on Sept. 9, it would have never aired.

MC: I guess Kissinger must still feel some gratitude toward the hijackers who distracted public attention. Back to Chile. The CIA plot to block Allende fails, Schneider is dead and Allende is inaugurated. So now what?

PK: Well, on Oct. 22, 1970, the commander in chief of the Chilean Armed Forces is assassinated. The Chilean public doesn’t blame Allende. They blame the logical source: right-wing military officers and General Viaux. Viaux’s people come running to the CIA, “Help us. We need to get out of the country. We’re going to be arrested.” And the CIA decides to pay them $35,000 in hush money to help them and their families leave the country so that they won’t talk about their many contacts with the CIA. A whole coverup operation begins. I’m not kidding. The documents show how frantic the CIA was to hide all of their connections to the murder of the Chilean commander-in-chief. And among other things, they send a special agent to meet with Camilo Valenzuela who doesn’t want to return the $50,000. He wants to keep that money. And according to one account, Seymour Hersh reported in his book on Kissinger, “The Price of Power,” a U.S. agent has to pistol whip Valenzuela in order to get the $50,000 back. Then they also retrieve from him the weapons.

MC: The machine guns sent by the CIA.

PK: That haven’t been used. And eventually, the military attaché and the CIA station chief go and throw the guns into the harbor in Valparaíso to deep-six them, to hide them. So a cover-up ensues. Hush money is paid to keep the plotters quiet. But of course, Allende is the winner in all this in a sense. The country is absolutely outraged that this political assassination has taken place and that there’s this threat to Chilean democracy. Allende was overwhelmingly ratified in Congress, and masses of people come out on Nov. 3 for his inauguration, and he becomes president of Chile. And the whole initial effort code-named FUBELT and known in CIA documents as “Track II” not only fails but backfires.

The stupidity, the arrogance, the malevolence, the maliciousness, the savagery, the criminality starting with the president of the United States going through Henry Kissinger, then-CIA director Richard Helms and all the way down to the agents who did this, albeit people who actually warned Helms that this wouldn’t work, is nothing short of astounding. And the documents that we have remind us of that. And then a whole new phase begins. Allende is president. And these next three years are going to be different. And it’s not that the policy of trying to undermine and thwart Allende changes, but the timeframe changes and so does the strategy — a longer-term strategy of destabilization, of creating a much broader set of chaos and turmoil so that a “coup climate” exists.

MC: So once Allende is elected or inaugurated, the Nixon administration and the CIA do not retreat from the plan. They simply modify it.

PK: The U.S. State Department — which was kept totally in the dark about the CIA plot and Schneider — drafts a letter for Nixon to send to Chile expressing condolences about an operation that secretly the president of the United States set in motion. So my point in sharing that with your readers is that a lot of this was top secret. It was not shared at all with others. And the State Department, actually their position was, “Allende is president. We can coexist with him, and we’ll just work over these next six years, just bolster the Christian Democrat openly and covertly…”

MC: For the next election.

PK: “… for the next election.” “No way,” says Henry Kissinger. “There’s going to be a National Security Council meeting on Chile scheduled for Nov. 5.”

MC: The day after Allende’s inauguration.

PK: Right, to decide what the new policy’s going to be. And the State Department is telling Kissinger, who is the national security adviser of the president, that he is supposed to coordinate. He’s not supposed to set the policy. He’s supposed to coordinate the policy from the Defense Department, the State Department and other agencies. The State Department is basically saying, “We’re going to come to this meeting. We’re going to present these policy and position papers that we think we can coexist with Allende and just work towards his defeat in the next election.” Kissinger is so concerned that Nixon will be swayed by these arguments that he goes to Nixon’s scheduler and he says, “Delay the National Security Council meeting by an entire day. Move it to Nov. 6 from Nov. 5. Let me have a meeting with President Nixon on Nov. 5 instead because I have a document to present to him.”

This document is the Holy Grail of explanations on why the United States cared, why Kissinger gave a damn about Allende’s election.

And the scheduler moves the meeting and Kissinger goes in, meets privately with the president, and presents this document which is titled “NSC Meeting, November 6th, Chile,” and dated November 5th, 1970. It is a secret sensitive memorandum for the president on White House stationery. And I just want to share with you the initial pages of this document, some of the key quotes, because this document is the Holy Grail of explanations on why the United States cared, why Kissinger gave a damn about Allende’s election. Just a year before, he’d said that Chile was a dagger pointed at the heart of Antarctica. And now, he cares enough about its strategic and geopolitical importance to literally violate every international law, violate all the stated principles of the United States respecting democracy, et cetera, and overthrow a democratically elected president.

And I searched and searched and searched for this document. It took years and years and years to find, but it’s invaluable. And he explains to Nixon that the NSC meeting is going to consider the question of what strategy we should adopt to deal with an Allende government in Chile. And his first section is subtitled “Dimensions of the Problem.” And emphasized, underlined, he states, “The election of Allende as president of Chile poses for U.S. one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere. Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will have to make this year, for what happens in Chile over the next six to 12 months will have ramifications that will go far beyond just U.S.-Chilean relations. They will have an effect on what happens in the rest of Latin America and the developing world on what our future position will be in the hemisphere. And on the larger world picture, including our relations with the USSR. They will even affect our own conception of what our role in the world…”

MC: Incredible. The delusions and illusions driven by the Cold War are at times mind-boggling.

PK: So he goes on. “The consolidation of Allende and power would pose some various serious threats to our interest and position in the hemisphere and would affect developments in our relations to them elsewhere in the world. U.S. investments totaling some $1 billion might be lost.” So there’s the whole economic rationale. “Chile will become a leader of [the] opposition to [the] U.S. and the inter-American system, the source of disruption in the hemisphere.” And then this, which is an eye-opener and which many people imagined was the argument that Kissinger might make. But seeing him make it is completely different. “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile,” with the emphasis on the word successful, “would surely have an impact on an even precedent value for other parts of the world, especially in Italy.”

MC: Where there was a large left in the Italian Communist Party. And when, at the time of Allende, the Italian CP was huge and could have easily entered government but did not.

PK: Euro communism. “The imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” And then he says, “While events in Chile pose these potentially very adverse consequences for us, they are taking a form which makes them extremely difficult for the U.S. to deal with or offset, a fact which poses some very painful dilemmas for us. Allende was elected legally, the first Marxist government ever to come to power by free elections. He has legitimacy in the eyes of the Chileans and most of the world. There is nothing we can do to deny him that legitimacy or claim. He does not have it.

“We are strongly on record in support of self-determination and respect for free elections. You, Mr. President, are firmly on record for non-intervention in the internal affairs of this hemisphere and of accepting nations as they are. It would be very costly for the U.S. to act in ways that appear to violate those principles. And Latin Americans and others in the world would view our policy as a test of the credibility of our rhetoric. On the other hand, our failure to react to the situation risks being perceived in Latin America and Europe as indifference or impotence in the face of clearly adverse developments in the region long considered our sphere of influence.”

They fear the example of popular socialists winning democratic elections, maintaining democracy but opposing some U.S. policies.

So he then explains, “Allende is going to move along lines that make it clear that he’s an independent socialist country not tied to the Soviet government or a communist government.” And yet he points out, and this is so important, Kissinger writes to President Nixon, “A socialist government in Latin America would be far more dangerous for [the] U.S. than it is in Europe precisely because it can move against our policies and interest more easily and ambiguously and because its model effect can be insidious.” That’s it. “Its model effect can be insidious.” And this was the motivation for Kissinger in convincing Nixon that he had to take a strong stand. And in the meeting the next day, you see Nixon — we have the memorandum conversation of the meeting the next day with the National Security Council — parroting this very language. He tells everybody, “Our biggest concern is that Allende will be successful and his model will move around the world.”

MC: So what you’re saying is that while some more well-intentioned, naive folks would argue, “Oh, well, if only Kissinger and Nixon had understood that Allende really was a peaceful democrat and he really wasn’t going to set up some terrible pro-Soviet dictatorship, they would’ve gotten along better with it.” In fact, it’s the contrary, right? They fear the example of popular socialists winning democratic elections, maintaining democracy but opposing some U.S. policies. Astounding.

PK: Italy. Italy.

MC: They are worried that there can actually be legitimate democratic, peaceful, non-Soviet-block socialist governments. They were right. I lived in Italy in 1976 and the Communists could have formed a democratic government with the Socialists but opted out.

PK: Kissinger is the ultimate chess player. He sees the impact Chile might have had on NATO countries, and Kissinger was thinking that Greece, Spain, Great Britain, France and others will start to elect progressive socialist candidates. And then they will take themselves out of NATO and NATO will be destroyed. And the whole structure of the Cold War division of the world will collapse. So this really is nightmare stuff for Nixon and Kissinger.

Well, here’s the worst thing of all. Kissinger was right and he was wrong. NATO countries did elect socialist prime ministers. But not a single one of them took their countries out of NATO or weakened their commitment to the NATO alliance. And so Kissinger was infected with a completely erroneous set of Domino theories, Cold War premises in which he was completely wrong in the end, and he takes the future of Chile into his own hands, manipulates and pressures the president of the United States, and the entire bureaucracy being told explicitly by his own aides that this is a complete violation of international law and violation of all of U.S. principles, and orchestrates the policy that contributes to the failure of Allende’s ability to move his agenda forward and the turmoil that brings about a coup and a bloody military dictatorship in 1973.

MC: I lived through it in Chile and it was no picnic. What was CIA destabilization like in Chile?

PK: And so at the National Security meeting the day after Kissinger met privately with him, Nixon parroted this very language, “Our biggest concern is that he consolidates and the model of his success goes out around the world.” Years later, there’s an official top-secret memorandum of conversation of that National Security Council meeting. But years later, just a few years ago, actually, on the 50th anniversary of that meeting in 2020, I was looking through various documents that had come out, and there were more handwritten notes by Richard Helms.

He was the director of the CIA, who was at the National Security Council meeting on Nov. 6. And Helms jots down Nixon saying something that’s not actually in the memorandum of conversation, the summary of the meeting. And it’s Nixon saying, “If we can unseat Allende, better do it.” And the CIA has always put out this false narrative that after the Schneider assassination, Track II failed.

MC: They gave up.

PK: The policy was never to overthrow Allende, but only to support so-called “democratic” institutions — like the “democratic institution” El Mercurio — which were calling, daily, for the overthrow of a democratically elected government. Right, and to support the opposition parties, but of course the CIA was supporting them in order to really be able to influence them to be against Allende, and for a coup. But here you had at the meeting the entire National Security Council sitting there, the president of the United States, once again recorded in notes of the CIA director, “If we can unseat Allende, better do it.” So the point is that for the next three years, the problem for the Nixon administration, which you see as you read through the minutes of this meeting, is as Kissinger put it, “Allende has legitimacy and there’s nothing we can do to make him illegitimate. And we have paid lip service to democracy and sovereignty and non-intervention.”

The CIA would shovel money into the political parties, buying up radio stations and expanding their communications abilities.

So the United States had to develop the Nixon policy, which became known as “Cool but Correct.” It was actually cool but incorrect. And the idea was that the United States would just quietly distance itself from Allende and then secretly try to undermine him through covert operations, through something that came to be known as the invisible blockade of quietly cutting off all external credits from the international lending institutions, the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, export-import credits from the United States.

MC: What did this covert subversion look like?

PK: There’s actually a memo from Kissinger to Nixon that spells out the four kinds of components of covert operations. The CIA will expand its contacts with military leaders in order to influence them and make sure they knew that we still wanted the coup. The CIA would shovel money into the political parties, buying up radio stations and expanding their communications abilities. The CIA would create a propaganda operation, which we’ve just recently come to know was called FUMEN.

And then whatever word they picked, and this coded named propaganda operation mostly focused on funneling money to El Mercurio and the Augustín Edwards empire.

It became the subject of some internal disagreement in the U.S. government. Some U.S. officials thought it was a waste of money because they thought the newspaper was going to go under anyway, and other U.S. officials thought it was a win-win situation. If a magazine went under, they’d just have another big propaganda whip to use against Allende. He was against the free press. He would have destroyed The New York Times of Chile. And actually, to resolve this disagreement, Nixon himself, after a conversation with Kissinger authorized this money: $1 million.

MC: And did the CIA continue financing the Christian Democrats?

PK: Well, yes. They funneled more money into the political parties so that they could buy radio stations, rent offices and expand their presence. And then they worked very hard to influence the midterm elections in Chile, which were actually in the spring of 1973, in which actually the Popular Unity candidates won more, raised their popularity rather than lowered.

MC: That was March 1973. The right-wing thought they were going to win two-thirds of Congress and be able to take Allende out through impeachment. And they got a big surprise as Allende’s coalition wound up at 45% at a time of economic catastrophe and social chaos — a 10% increase over his presidential vote. So it must have scared the piss out of the opposition who was sure he would be toast.

PK: Well, it did, and you can actually read the CIA reporting after this failed effort to influence these elections in 1973, the Congressional and Community elections. There was a series of memos. It basically was that Allende is becoming more popular despite all our successful efforts to create turmoil and upheaval here, and the discussion started to gravitate more and more toward the military acting.

MC: No more Mr. Nice Guy. Back to the remedy of a military coup.

PK: Back to a coup scenario. Now, you have many people thinking that the CIA just all along was in touch with the Chilean military and that everybody was coup-plotting all along. And that’s not how it worked at all. And I just should caution people who think they know what the history is, that the history is in the documents. You actually have to read, we have so many of them now that you can almost read a day-to-day account of how this evolved. And it’s hard to imagine, but even though there are documents that show that Pinochet himself was talking about a coup as early as 1972 when he was meeting with U.S. military officials in the Panama Canal zone, he was on a trip to buy U.S. weapons. And there was a whole conversation about a coup, and some military guy says to him, “Well when you’re ready, we’re with you.” And the U.S. military role in Chile has taken a second seat to the CIA role. And really, I think as a historian, we owe it to spend more time focusing on what the military was doing.

MC: Chileans were quite aware of CIA meddling. Many blamed the CIA for a costly transport strike in 1972 but you have told me there is no documentation on that. But were there CIA folks on the ground organizing against Allende?

PK: In many ways. But by that time, one of the most symbolic protest techniques was the upper- and middle-class women banging pots and pans claiming they were starving. There was a young CIA agent on one of his first postings in Chile named Jack Devine. And he had these bell-bottom pants and this kind of big head of hair. He looked like a hippie. And he was actually the bagman for El Mercurio. He would go up with the cash for El Mercurio.

But finally, just a few years ago, he published his memoirs of his rather legendary career as a CIA officer. And he wrote in his chapter on Chile that he had paid the first woman $350 to start banging a pot.

MC: I believe that. That’s fantastic. That was a ton of money back then in Chile.

PK: And that she had taken the money, gone ahead and gotten her neighbors, organized her neighbors in one building, then gone to the second building next door and then gone. And then before you knew it, everybody was, all these women were banging their pots and pans in the streets.

MC: I will note that when they did they were flanked by columns of fascist youth from the Patria y Libertad group decked out in helmets, masks and nunchucks, who proceeded to attack and burn down leftist offices as the pot and pans march ended.

PK: And the whole thing started with this minuscule CIA investment in this one grumpy woman, which is a priceless little nugget of history, that the actual pots and pans campaign started with the CIA.

MC: Take us back to those 1973 midterms that the right so misjudged. So the U.S. aspirations for the midterms flop, right? Would it be fair to say that after those March 1973 elections where there was no longer the possibility of removing Allende through Congress by being impeached, that there is now a hard decision taken that we’ve got to do the coup?

PK: No, there are no hard decisions. The whole policy was designed to create this coup climate over a longer term, as Kissinger would later put it, to create the conditions as best as possible for a coup. And that is what they worked towards throughout these three years, actually participating in a coup, and getting really close to coup plotters, really close, providing weapons, providing strategy. The CIA got spooked from doing that for two reasons.

One is, people forget that the CIA had really gone out on a limb to basically assassinate Rene Schneider, of course, on the idea that the military leaders would understand that was part of the plan, that was their opportunity and act. Then they hadn’t acted. And the CIA people who were involved in that still one year, two years, three years later — they were still in place. David Atlee Phillips sure was. He was head of the task force on Chile in 1970, but he was head of the Western Hemisphere division by 1973. And he remembered that what he thought was the spineless Chilean military hadn’t acted when the CIA went out on a limb to create that moment. And he did not want to basically be pushing Chile, the CIA doing operations that were designed to push Chileans out into the street unless it was clear that the military was ready to act. So he has set a number of conditions for closer collaboration on a coup. One of them was that Schneider’s successor, Gen. Carlos Prats, who like Schneider was pro-constitutionalist, and who Allende brought into the cabinet, trying to inoculate his government against the military moving, had to leave. That was one of the CIA’s positions. Prats has to go in order for the coup conditions to mature, but there was a second condition: The Christian Democrats have to stop negotiating with Allende over a possible plebiscite referendum on the future. They have to declare that negotiations are fruitless and that only a military move is the solution.

MC: Allende brings Gen. Prats into the government as interior minister. But then six months later, a few weeks before the coup itself, he is forced to resign after an aberrational demonstration in front of his house organized by other active duty officers including other generals who wanted him out.

PK: That’s right. And that’s exactly when the momentum toward the Sept. 11 coup started. Prats is forced out in late August, and then the Christian Democrats declare under great U.S.-CIA pressure, I believe, that they’re ceasing negotiations with Allende and just right at the end of August of 1973.

MC: It was exactly that. Well, even before that, in a sense, the Christian Democrats had formed an alliance with the right-wing National Party for those midterm elections. And yes, the Christian Democrats came out with the declaration, you may know the date, I can’t remember, sometime in August when they basically said, “We’re in favor of a military coup.” This was ostensibly once a center-left party that had become a cat’s paw for Nixon.

PK: That’s right.

MC: Did the CIA have a hand in that? Do we know?

PK: Well, I think, yes. I think that was one of the conditions that the CIA had set.

MC: Are there documents on that?

PK: Well, the documents show that the CIA wanted the Christian Democrats to do that, and that had been their position. And of course, one of the points of funneling lots of money to the Christian Democrats over that three-year period was to be able to have access to them and influence their decisions.

What I want to disabuse people of is this idea that it was like this solid position where they were promoting a coup or fomenting a coup for the entire three years. In fact, it was that they were trying to set the conditions for a coup. We don’t know if the coup is going to happen because the military failed us in October of 1970 when we gave them all the opportunities they needed, and these Christian Democrats keep talking to Allende. And so, the CIA leadership in Washington’s position to the station was that Chile now has the circumstances for upheaval.

We want to have a new propaganda campaign that calls people into the street, mass protest. We’ll get El Mercurio to do this, to do that. And the CIA leadership goes, “Look, we don’t want a bunch of people in the streets and then being repressed by the very military, the police forces that we think we’re supporting.” There’s no evidence yet that those military guys and police forces are not going to take orders from Allende. So we don’t want to be responsible for sending people into the street, and then them getting mowed down. So the conditions we see before we call for people to be in the streets, before our programs start to focus on that, is the Christian Democrats stop negotiating with Allende, and Prats gets removed from the cabinet.

MC: Talking about disabusing people of ideas. In August 1973 there really was a cabal of Chilean military planning a coup. My understanding is that the CIA was not at that coup plotting table as active conspirators. Thinking it was the CIA orchestrating every detail, that’s not at all the case.

PK: That’s not the case. We have a document from former CIA operative Ted Shackley of all people basically saying we’re going to raise the budget for contacts with the Chilean military so we can influence them to act. That’s the operative thing. It wasn’t so we can get information from them as the CIA would later claim, “We’re just gathering information.” No, he specifically says this money is so that we can influence them to act. And there was another problem. There were a lot of intricacies here about coup-plotting on both sides. The Chilean military was actually suspicious of the CIA.

The U.S., the CIA and the State Department actually sat down with each other in the early summer of 1973 and basically tried to game out the situation.

And the Chilean military is pretty nationalist, and not really eager to share their plans with the CIA. But the CIA did have a number of sources and a number of contacts. The U.S., the CIA and the State Department actually sat down with each other in the early summer of 1973 and basically tried to game out the situation. What should the United States do if the military said, “Well, we are interested in a coup, but we want your help.” And the CIA’s position also, that it would be very unlikely that they would take that position. But if they did, our position is that they’re capable of doing this on their own if they want to. The thing is, they have to want to, and our experience with them in 1970 was they didn’t want to. And by the way, let us point out that there just was an attempted coup in June. The Tanquetazo, led by Roberto Viaux, went nowhere really fast as it involved only one small tank unit.

And so, it appeared to the U.S. officials that the time just was, the fact that stars had not aligned, and the circumstances were not there for this to happen. And even though the United States would continue to work towards that, the pieces hadn’t fallen into place. But they do fall in place at the end of August of 1973, and you literally see then the progression almost starting on the first day of September towards an actual coup.

MC: What is it you detected in the memo traffic beginning that first day of September?

PK: The CIA itself starts to report on the forces that are moving, that they’re pushing the country towards a coup, and those forces are all coordinated. They involve the truckers’ unions and the taxi unions. They involve El Mercurio, which the CIA reports is the bullhorn of opposition to Allende, and they involve the military and Patria y Libertad. And the thing is that the CIA points out that these forces aren’t acting independently. They’re coordinating.

El Mercurio is on the CIA payroll. So this, and later the CIA will say, “Our support for El Mercurio set the stage for the coup of September 11th, 1973.”

MC: From this end of the telescope on the ground in Chile it certainly seemed that the Chilean military and the right wing were coordinated and were more than ready to stage a coup. That became dead obvious around the middle of August when the military begins carrying out its own weapons search operations, even against its own government.

So is it fair to say that, in general, the forces in Chile had come together, they were moving forward inevitably toward a coup, and the CIA hitched onto that and encouraged it? I mean, that’s rough language, but…

PK: The CIA was always encouraging…

MC: But the actual operational initiative was coming from the Chileans, wasn’t it?

PK: Oh, absolutely.

MC: So take us to that first week of September.

PK: Well, you see a day-by-day countdown toward a coup. If you just line up in chronological order the CIA and State Department reporting, it starts in mid-August. The head of the Western Hemisphere Division David Atlee Phillips sends a veteran agent to Santiago to assess the situation. He comes back and reports, “In the past several weeks, we have again received increased reporting of plotting and seen a variety of dates listed for a possible coup attempt.”

MC: I guess the point I’m trying to make is that — without underestimating at all the role of the CIA, and you’ll correct me if I’m wrong — at least up until the day of the coup and probably beyond that, the CIA was not running the coup operation.

PK: The CIA was never in charge of the Chilean military. The Chilean military was not a pawn. It was not a client. It was not a puppet of the United States. The Chilean military had a deep, Prussian-trained, almost Germanic background as an institution. The heads of the military agencies, the Army, the Navy and the Air Force — became very pro-coup. The issue was they had to get rid of Prats as their commander-in-chief, which they did, and the Christian Democrats had to fall into place, which they did.

Then the coup plotting very much picked up. Let me just quote one intelligence document from Aug. 25, that “the departure of [General] Prats has removed the main factor mitigating against a coup. And on August 31st, the U.S. military had sources in the Chilean army that were reporting that “the army is united behind a coup and key Santiago regimental commanders have pledged their support. Efforts are said to be underway to complete coordination among the three services, but no date has been set for a coup attempt.”

So basically the coup plotting gels, literally, in the last days of August of 1973, and then moves very quickly. And by the 8th of September, actually, the Defense Intelligence Agency is reporting that there’s a coup set for Sept. 10, and then it gets set back by 24 hours because of coordination and moving people around and moving tanks and all these things and it’s set for Sept. 11. But you know the CIA only actually reports that on Sept. 10 it was the next day and it turns out to be Jack Devine, the same guy who started up the pots and pans demos has a source, who says, “I’m leaving the country because the coup is going to be tomorrow.”

But there’s one other thing, which is that on Sept. 10, one military guy, a Chilean military guy, comes to the CIA and says, “If Allende’s forces proved to be strong and resistant and fighting gets prolonged and protracted, will you support us? Will you come to our aid if we need it?” So this memo, this request is, literally, on Kissinger’s desk—

MC: In the morning of Sept. 11.

PK: Yes, on the morning of the coup itself, Sept. 11. And of course, in the end, as you know better than anybody, Allende’s forces were not able to hold off the military.

The concern that the Chilean military had that they might meet real resistance from the workers and from Allende’s supporters proved to be unnecessary.

And I just want to read you the first report from the head of the U.S. Military Group in Valparaiso, Lt. Col. Patrick Ryan.

He files this report. “Chile’s coup d’etat was close to perfect.” It’s really important that you understand the way these guys talk. This was in his first “sitrep,” which is short for “situation report.” He reports that by 8:00 a.m. on Sept. 11, the Chilean Navy had secured the port city of Valparaiso and announced that the Popular Unity government was being overthrown in Santiago, the Carabineros were sent out to detain Allende at his residence, but he managed to make it to the Moneda. He reports on the jets attacking the Moneda Palace.

Later, the CIA would consider trying to make propaganda of the fact that Allende had supposedly turned down safe passage. But that was a complete farce and canard because, in fact, a couple of things had happened. One is he had sent a delegation of his top advisers to meet with the military to discuss conditions to surrender the Moneda and they’d all been arrested. So they’d never come back from this effort to have a dialogue on that day of the coup.

Then Pinochet himself was recorded on a radio transmission.

MC: By a fellow Chilean ham radio guy.

PK: Yeah, they were going to put him on a plane and then shoot it down. And you have Pinochet’s scratchy, high-pitched voice saying the plane will never land. Kill the bitch and you eliminate the litter. That was the plan that Pinochet had. And I think Allende certainly understood this, and he took his own life instead.

MC: You said initially the State Department was not looped into the CIA’s first plots against Chile. But by the time of Allende’s overthrow in 1973, the Nixon State Department must have had an equally hostile view of Allende and welcomed the coup.

PK: Assistant Secretary of State Jack Kubisch says, “Our policy on Allende worked very well,” in a meeting with Kissinger and in the first meeting that Kissinger calls of this Washington Special Actions group, which is a group designed to speed up a U.S. reaction to anything. But in this case, it’s the U.S. reaction to the coup, which is, we have to get aid to the new military regime very quickly. We know bureaucratic hang-ups so let’s get this, turn on the spigots.

Kissinger jokes during that meeting, which takes place the day after the coup, that President Nixon is worried that we might want to send someone to Allende’s funeral. “I said that I didn’t believe we were considering that,” Kissinger said. Then somebody jokes, “No, not unless you want to go Mr. Kissinger.”

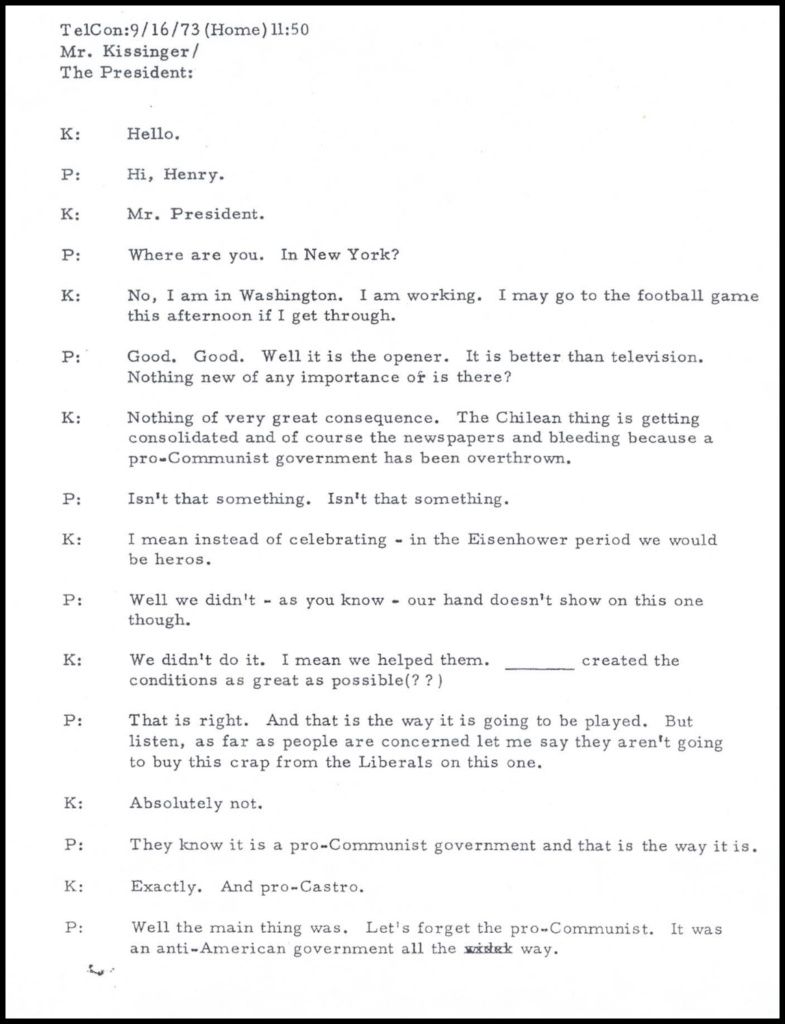

Then, even more extraordinarily, Nixon picks up the phone and calls Kissinger just a few days after the coup, and he asks for an update. Kissinger says, “The Chile thing is consolidating,” referring to the new military regime. Kissinger says, “The liberal press is bleating, bleating like a lamb, that Allende’s Communist has been overthrown.” Nixon is like, of course, in total agreement. “Isn’t it something? Isn’t it something?” he says that the liberal press won’t give them credit. And Kissinger says, “Yeah. You know, in the Eisenhower days, we would be heroes.” And the two of them were commiserating.

MC: I doubt they were much distraught over the death of Chilean democracy and several thousand Chileans.

PK: The two of them are commiserating on the telephone that, A) they can’t openly take credit for this great Cold War victory that they’ve been working towards for three years and, B) discussing what the U.S. role really was. Nixon is worried that our hand is going to show, so he asks Kissinger, “Our hand doesn’t show, does it?” Kissinger says, “We didn’t do it,” meaning, we didn’t participate directly in the coup. Then he says, “I mean, we helped them.” “[Missing word],” which is a reference to Helms or the CIA “created the conditions as great as possible.” And Nixon responds: “That’s right.”

Stay tuned for the upcoming Part 2 of this interview.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.