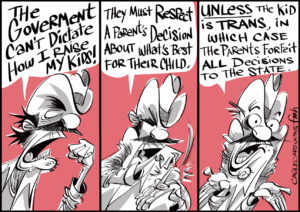

Lesbians Are a Target of Male Violence the World Over

In many countries, they have won legislative equality. But the grim reality is that they still have reason to fear for their safety. Ugandan LGBT rights leader Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera, founder and executive director of Freedom & Roam Uganda (FARUG). (Kathy Willens / AP)

Ugandan LGBT rights leader Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera, founder and executive director of Freedom & Roam Uganda (FARUG). (Kathy Willens / AP)

Since coming out as a lesbian at the age of 15 in 1977, I have seen the world change for the better. When I met other lesbians soon after leaving home to find the “gay scene,” I was shocked to hear stories of women losing custody of their children, in some cases to violent ex-husbands, for the simple reason that they were in a same-sex relationship.

Over the decades in the U.K., I have seen and experienced anti-lesbian violence firsthand. I have been attacked on more than one occasion—physically assaulted by anti-gay bigots, and sexually assaulted by a man who thought he could “straighten me out.” I’ve lost housing and jobs as a result of being a lesbian.

The first time I was physically attacked was in a gay and lesbian bar in the U.K. I was 16, and out with David, a gay friend who had taken me under his wing. We were dancing and laughing, having great fun. David was encouraging me to talk to other girls, but I was too shy. Suddenly, a small group of men was upon us, pointing their fingers in our faces. “Are you a puff [faggot]?” one of them asked David. “Prove you are a proper man and fuck her,” another growled, pulling me over to David by my hair. I was terrified, and David started crying. People had begun to notice what was happening, but no one approached us.

The men were big and menacing, with shaven heads and combat clothing. I lived close to a garrison town, and there were high levels of sexual assaults by soldiers in the vicinity.

After a few minutes of being swung around by my arms and my hair, and David being jabbed in his stomach and groin, the men spat at us and left the club, laughing. David and I never spoke of the incident—he, I suspect, feeling the deep shame and stigma that I did.

A year later, I moved to a large city in the north of England. Leeds was far more diverse than my home town, but unfortunately had become a key base for a group of fascists known as Combat 18 (the numbers 1 and 8 representing the numerical order of Adolf Hitler’s initials in the alphabet).

I lived in a hostel with my girlfriend, who was black. Our windows were regularly broken by young fascist males, and graffiti daubed on our front door. One evening, we were chased through a park by skinheads brandishing chains, shouting that they were going to “skin and rape” the “black bastard” and her “n*****-loving queer.” We escaped into a neighbor’s house, where we had to endure a lecture on how we had brought “trouble to the neighborhood,” and the neighbor demanding to know whether we had to “shove what you are down everyone’s throats.”

At the time, I had a job cleaning in a gay and lesbian bar that was run by a straight couple, Bob and Doreen, and their son, Simon. Bob and Doreen had retired from the police service, and saw financial opportunities in running a bar for the many lesbians and gay men who had gravitated to the city from the surrounding rural areas and small towns. “The queers have loads of money,” Bob used to say. “They don’t have kids to feed.”

One day, when I was cleaning the apartment above the pub, Bob and Simon attempted to rape me. They were laughing, telling me I needed a “good fuck.” I managed to escape only because they heard Doreen come up the stairs.

There have been many other times when I have been attacked or endangered by men who targeted me for being a lesbian. I was once thrown down the stairs by a nightclub bouncer and punched in the face by a man in the street when I refused his advances. I learned to fight back, stay out of nightclubs, and to view these attacks as part of a misogynistic backlash by men who feel threatened by women’s sexual and social autonomy.

Throughout my early years, there were very few public role models. The depiction of lesbians was hardly flattering. Butch, predatory and deeply unattractive, these images served as a warning to women not to “cross over to the dark side.”

Lesbians in the U.K. have fought for and achieved legislative equality with heterosexuals. We can marry, adopt and foster children, and have next-of-kin rights with a same-sex partner. It is now illegal to fire us from our jobs or refuse goods and services on the grounds of our sexuality.

These changes also are prevalent across the majority of states in the U.S. and in numerous other countries around the world. But there are still plenty of places that have either rolled back the rights of lesbians, such as Russia under President Vladimir Putin, or, under the influence of religious fundamentalists, have introduced archaic and extremely punitive legislation affecting LGBTQ people.

I decided to investigate the horrific story of violence towards lesbians, because this is a tale that is rarely told. “We hear about the oppression of gay men and of trans people,” one senior U.N. official told me at a meeting on sexual orientation and gender identity rights, “but rarely do lesbians come anywhere near the top of the list, even when we are zoning in on LGBT rights.”

Uganda

My journey took me to Uganda, a beautiful country in East Africa that has some of the worst legislation on and social attitudes toward lesbian and gay rights on the planet.

Its Parliament passed an anti-homosexuality bill in 2013 that lengthened sentences for consensual homosexual sex and extended punishment to those promoting homosexuality. It is illegal to be gay in most African countries, and in Uganda, same-sex encounters can land a person in prison for, on average, seven years. Same-sex marriage is illegal.

The first LGBTQ organization in Uganda was Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG), founded in 2003 by three lesbians. I met Gloria, who joined FARUG in 2015, during a recent trip to Uganda. She explained what a struggle it has been to keep the organization afloat in a country so openly hostile to LGBTQ people.

“In our community, butch women, dykes and lesbians face the most stigma, discrimination and violence, because the world was seeing them as men,” Gloria said. “We knew they were going to be targeted, but what happened has a lot to do with the trans movement, especially trans men. Many of the out trans men started as lesbians. I think they discovered their identity as they went on. So, many people are going to be targeted, not only lesbians but even trans men still in the process of trying to deal with the changes to do with their sexuality.”

Homophobic legislation in Uganda has its roots in the religious right in the United States. In 2009, American evangelist Scott Lively traveled to Uganda to set up an anti-gay movement, enlisting support from local preachers such as Pastor Sember, who ran a church within Makerere University. “The evangelists started the anti-gay movement and would go into churches preaching hate against LGBT persons. Before then, there was hate, but there wasn’t a solid religious propaganda, so they started that movement,” explained Gloria, who was a student at Makerere at the time. “Pastor Sember stands in church one Sunday and says, ‘We’re going to have a huge crusade that is aimed at fighting homosexuality in Uganda.’ They got around 10,000 people on that crusade, and there was a lot of hate speech. During that crusade they were talking about how homosexuality is infiltrating the nation, and how white people have brought homosexuality here and how they are paying Ugandans to become homosexual.”

The result was a build-up of public anger toward the LGBT community in Uganda. “We knew they were coming after us,” Gloria said. “During that time, FARUG struggled a lot. In 2016, our organization operated without money. I remember having an extraordinary meeting, and the person who is now our director stood up and said, ‘This is our child. If we do not stand, this organization is going to fall, but I need you to understand that we started this movement. When I talk about the movement, it’s not just about me, it’s about you. It’s not just us the activists, it’s the fact that you can still move in the street, that you can still access medical care, that we can still represent you in court when people are being terrible to you.’”

I spoke with Amanda, 29, who came to FARUG for “social Friday,” a monthly gathering where LBQ women can relax with their friends, meet new members and, later in the day, drink and dance.

Amanda was present at the notorious police raid of the Venom bar in 2016. “There were police all over the place accusing us of holding a gay wedding,” she recalled. “They said we were thieves and arrested us on the premises. It was so scary. I phoned my sister and said, ‘If anything happens to me, I am at this place.’ We were there for hours. Then some kid jumped off the fourth floor of the building to escape the police. It was so bad.”

Simon Mpinga is the pastor at the Living Gospel World Mission church in Kawuga village, on the edge of Kampala. Mpinga also preaches at the Fellowship of Affirming Ministries church, known for its inclusion and acceptance of lesbians and gay men. I went to meet him with Nasiche, a lesbian who told me she refuses to give up her faith “just because of those pastors that hate us.”

Mpinga greeted us at the door of his small church, which was full of congregants enjoying a meal of rice and beans. Tall and handsome, he was wearing a bright T-shirt and a big smile. I asked what led him to open a LGBTQ-inclusive church in the face of such resistance. “As I was growing up,” he explained, “I saw bigotry towards LGBT people happening in the churches. The moment people discovered that someone was gay or bisexual, they would push them out of the ministry, discriminate against them, speak ill about them; they would be psychologically tortured and become depressed. It was a terrible thing.”

I asked what specific problems lesbians face in Uganda. “Initially, the women were oppressed just for being women,” he answered. “So I think that the women are in double jeopardy. They are women and they are sexual minorities. Women are looked at as weak, they are unrecognized in society, especially in African society because, when you look at the different religions here, they don’t recognize women. They are not ordained as priests; they cannot be given the pulpit to speak about anything. So, we need to concentrate on the lesbians.”

I met with Ruth Muganzi from Kuchu Times, Uganda’s LGBTQ media platform. “We set up KT in December 2014, just after Uganda had passed what we call the ‘identify and kill the gay bill,’” she told me. “We realized the media had been a very powerful tool in the hands of the anti-government movement. They [could] tell false stories about how gay people deal with money and children. But these media spaces never allowed gay people to share our stories, so we created KT. There was a need for our stories to be out there; there was a need to question the things that were being shared. There wasn’t a space for us, so we created our own.”

I met Namazzi as she was coming into the FARUG Friday social. “I told my best friend [that I am a lesbian] and the first thing she said was, ‘You are beautiful. Are you telling me there are no men out there who want to be in a relationship with you, so you decided to go and have a relationship with girls?’ So, I told her, ‘No, it’s because I want girls; the men are there, but I want girls.’ We are still friends, but not best friends anymore.”

Very few of the coming-out stories I heard at FARUG were positive. “I have lost some of my family members,” Lailah told me. “Some don’t talk to me, some don’t understand me. At Christmas, you’re expected to go to the village and be with your family, but they say, ‘That one, she’s gay.’ So, I don’t go home. I call and talk to them, but it’s really hard. I miss my family.”

Annise was sitting on the floor of the courtyard, drinking a beer, her baseball cap pulled low over her face. “My friend was in an abusive marriage and her husband thought she was a lesbian with her best friend,” she told me. “When she ran away from the marriage and the abuse, the husband followed her to her friend’s house because he thought they were lovers. He tried to attack them and keeps threatening to kill them.”

Over and over, the women at FARUG spoke about police brutality. “Some friends and I were listening to music and drinking at a bar when the police suddenly arrived,” Hope recounted. “I saw some people jump over a wall to escape the beatings, and others hid in the toilets. Those of us who were left were ordered to stand in a corner. The police then marched us slowly all the way to the police station.”

Grace, a 30-year-old feminist activist and proud lesbian, approached me at FARUG and told me that she is “sick of gay men and trans women demanding all the attention from the international community. We are the mothers of the movement; we are the ones to start the revolution. We have less representation. We don’t have the faces and voices out there to amplify our issues the way we need them to. I don’t know if it’s because we’re shy and most of us are in the closet. We have less of a profile.”

On my last day in Uganda, police raided an International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia event in Kampala. When I arrived with Mutyaba and others, we saw police officers guarding the entrance and dozens of people waiting nearby. “This is disgusting,” said Natukunda, a young, butch lesbian in her 30s who had travelled almost 20 miles to attend. “Police don’t have a legal right anymore to stop us meeting in public, so they say they heard a gay wedding was taking place.”

Eventually, a new venue was found, and dozens of LGBTQ activists moved the food, beer and sound system from the original venue, while armed police officers stood by. The party was in full swing by the time I left for the airport. As I was saying my goodbyes, shouting over the loud reggae music, one of the young women, proudly embracing her girlfriend, told me, “This movement is not going to end. We are getting bigger; we are getting stronger.”

Brazil

When Marielle Franco, a black lesbian activist, was murdered in Rio de Janeiro in 2018, she became the symbol of the campaign to end violence against women in Brazil. Franco was shot dead while returning from an action she had organized called Young Black Women Moving Structures. Franco was one of the few activists who dared to speak about the political violence in Brazil. The term “lesbocide,” first used by a collective of lesbian women in Chile, means “the death of lesbians as a result of lesbophobia or hatred, repulsion, and discrimination against the lesbian existence.” Lesbocide is on the rise, and lesbians all over the world are endangered by this misogynistic hatred.

FannyAnn Eddy, 30, was found dead one morning in 2004 at the Sierra Leone Lesbian and Gay Association’s offices. Her assailants had raped her repeatedly before breaking her neck and stabbing her. That April, Eddy had spoken at the U.N. Commission on Human Rights. “We face constant harassment and violence from neighbors and others,” she had said. “Their homophobic attacks go unpunished by authorities, further encouraging their discriminatory and violent treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.”

Between 2014 and 2017, the murders of lesbians in Brazil alone increased by almost 25%; the majority of the victims were young and black.

I spoke to Milena Peres, a 25-year-old lesbian, over Skype. Peres is on a team of researchers in Brazil that is investigating the murders and suicides of lesbians. She came out in her early teens and suffered as a consequence. “I suffered abuse from my family, school colleagues and people in general,” she said.

According to Peres, “The murder or suicide of a lesbian plays the social role of frightening other lesbians, demoralizing and devaluing the lesbian existence, as well as enhancing men’s power over the lives and deaths of women.” If a lesbian is raped, it will be recorded as a rape only, and not a specific hate crime against a lesbian.

Luana Barbosa dos Reis Santos was murdered in 2016. She was stopped and searched by police in the favela where she lived. When she asked to be searched by a female officer, the police considered her request a sign of contempt for their authority, and and they attacked her in front of her entire family. She died five days later as a result of her injuries. Before she died, Reis Santos recorded a video describing the violence. She has become an important symbol of lesbian resistance in Brazil. “We want justice for Luana, because the situation has never been resolved, and her family and the people involved in the case are still facing situations of great danger and pain,” Peres said.

A report titled “Dossier on the Killing of Lesbians in Brazil” shows the alarming increase in the number of lesbians murdered in the country over the last few years. According to the study, 180 lesbians were reported killed between 2000 to 2017. The publication was compiled by the Research Group on the Killing of Lesbians – The Untold Stories, an association that gathers data and stories about gay women who fall victims to this crime in Brazil.

“Lesbophobia isn’t just an act of specific violence that can occur at any given moment,” Peres said. “What we suffer from also defines us. We are isolated, discredited, made invisible, attacked and violated in the most diverse ways every single day. Death lurks after us, as does mental illness, profound isolation and the aforementioned systematic devaluation.”

A poll of 800 lesbians in Brazil found that more than 80 percent reported having suffered some form of anti-lesbian violence. Forty percent said they were unemployed, more than three times that of the general population. “The women seen as not complying with so-called feminine standards are virtually always the most strongly affected in job interviews”, Juliana told me. An accountant in her 40s, Juliana lives with her partner, Marcia, and their child. “I am always turned down for jobs, despite being better than the male applicants,” she said. “The boss will say, ‘This man has kids, you are a woman, your husband can look after you.’”

Suane Soares is a professor of bioethics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, where she researchs human rights and feminism. “I was raised in a family in which the expression of a lesbian sexuality was highly reprimanded,” said Soares, who came out as a lesbian six years ago at the age of 28. “It was only by coming into contact with feminism and by becoming financially independent that I had the opportunity to define and fully understand myself as a lesbian. I lost a lot of personal ties, spaces and opportunities with people who never accepted me.”

Brazil is a country marked by profound social and cultural inequalities. To be a lesbian in the northern region, I was told by those I interviewed, is very different from being a lesbian in the south. And white lesbians have very different experiences from black, “quilombola” or indigenous lesbians. “The lesbian invisibility is expressed through the systemic annihilation and denial of the lesbian existence, of the disparagement and creation of myths about us which do not speak truth to who we are and how we live,” Peres said. “When we are murdered, our deaths aren’t accurately disclosed, and our memories are disrespected.”

London

Earlier this year, in my home city of London, two lesbians were beaten up by a group of men when they refused to kiss in front of them. The image of the bloodied, distressed women attracted international media attention, but violence by members of the public is commonplace for lesbians in England.

In Walsall Garth, toward the north of England, Ellie-Mae Mulholland, 18, was beaten in July by a gang of men who told her, “You and your girlfriend are going to get it 10 times worse next time.”

Even some gay men have contributed to the culture of aggression and contempt toward lesbians in the U.K. Last year, at Manchester Pride, one of the organizers said of a small group of lesbians who were demanding better representation and inclusivity at Pride events, that they should be dragged off by their “saggy tits.”

Iran

In Iran, women’s rights and their freedom of movement and expression are extremely restricted, and the strictly patriarchal structure allows fathers, brothers and husbands to assert direct control over women and girls. For lesbians, life is especially difficult.

“Being Lesbian in Iran,” by the human rights campaign group OutRight International, found that violence and abuse is endemic.

Maryam, a lesbian from Tehran, was forced to marry her first cousin when she was 14. He was 22 years her senior. From the beginning, she had no physical or emotional attraction to her husband. In response, he became abusive and forced Maryam to see a doctor to “cure” her lack of sexual interest. The medication she was given made Maryam very depressed.

Finally, after years of abuse, violence and marital rape, Maryam managed to get a divorce. She entered a relationship with Sara, but, because of family pressure, could only see her secretly. At one point, Sara contemplated undergoing sex reassignment surgery so that she could legally live with Maryam. The couple finally decided to run away to a small town in northern Iran. In response to a neighbor’s complaint about the two women living together, police raided the couple’s home and arrested them.

The police held them, separately, in detention for several days and pressured them to confess the nature of their relationship. Following a 30-minute trial based on their forced confessions, Maryam and Sara were each sentenced to 100 lashes and jail time. Maryam said that she and her partner were both flogged on the first day of their imprisonment. They suffered intense physical and psychological trauma as a result.

Azadeh, in her 20s, is from northern Iran. She was abducted by intelligence officers and forced to undergo a “reorientation course” and violent interrogation after they became suspicious of her sexual orientation. “The interrogators tortured me by pouring boiling water on my skin and beating me, especially on the head,” she said. “More than physical torture, I was subjected to verbal abuse. They kept telling me that I was a ‘pussy licker.’”

The Global Picture

Lesbian human rights campaigner Yelena Grigoryeva, who campaigned in Russia for LGBTQ rights and freedom for Ukrainian political prisoners, was murdered earlier this year near her home. According to friends, Grigoryeva had reported threats of violence to the police, but no action was taken.

In 2018, two women, aged 22 and 32, were found guilty of “attempting to have sex” in the conservative state of Terengganu, Malaysia. They were each caned six times in the country’s high court, an event witnessed by 100 people. It was the first time women were caned for lesbianism. Activist Thilaga Sulathireh, from Justice for Sisters, was in the court at the time. “It was shocking, and it was a spectacle,” she recalled “This case shows a regression for human rights. Not only for LGBT people, but all persons.”

So-called corrective rape is common in South Africa. Women suspected of being lesbians are often targeted and assaulted in order to “make them straight.” In Cape Town, I met Precious, a 19-year-old who was gang-raped near her township by a group of men who told her she “had the devil in her.”

“They told me I was evil,” she said. “One of them said he would beat the evil out of me, but through my vagina, because that is where the devil had taken hold of me. I am now HIV positive and have been rejected by my family. Even my girlfriend left me, because they put the fear of God into her, as well as me.”

Sarmilla Malla, a 19-year-old in the Jagatsinghpur district of Odisha, India, was tied to a tree and beaten when she was found in bed with her girlfriend. The following day, Malla told the local press, “I was dragged out of my house by my neighbors. They beat me up and tied me to a tree. They abused me and kicked me when my parents tried to rescue me. We are madly in love with each other.”

In the U.S., lesbians are not safe from harm. In New York last year, a 20-year-old woman was hospitalized and suffered a broken spine after being attacked in the subway by a man using anti-gay slurs, according to the New York City Police Department. As the woman walked away, the man grabbed her from behind and pushed her to the ground, smashing her head on the pavement.

In addition to violence and sexual assault by men, many lesbians worldwide suffer from the intolerant and archaic attitudes of others.

In Cincinnati, Tiffany and Albree Shaffer were fundraising in May to pay for medical bills for their 18-month-old daughter, Callie, who was diagnosed with cancer. The couple set up a GoFundMe page to help with the spiralling medical costs. Then the couple received a message from a woman on Facebook: “My prayers for Callie. I was going to donate $7,600 to her but I found out her parents are lesbian. I’ve chosen to donate to St Jude due to that fact.”

Hatred of lesbians is a result of patriarchal attitudes that demand subservience and capitulation to men. Lesbianism is a threat to bigoted misogynists who believe women need to be “kept in line,” either by a father or a husband. Lesbianism is an affront to these men, for the simple reason that we have refused compulsory heterosexuality and have openly and unashamedly rejected men sexually. Until we eradicate sexism, anti-lesbian violence will be all too common.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.