The Link Between Violence and Female Incarceration

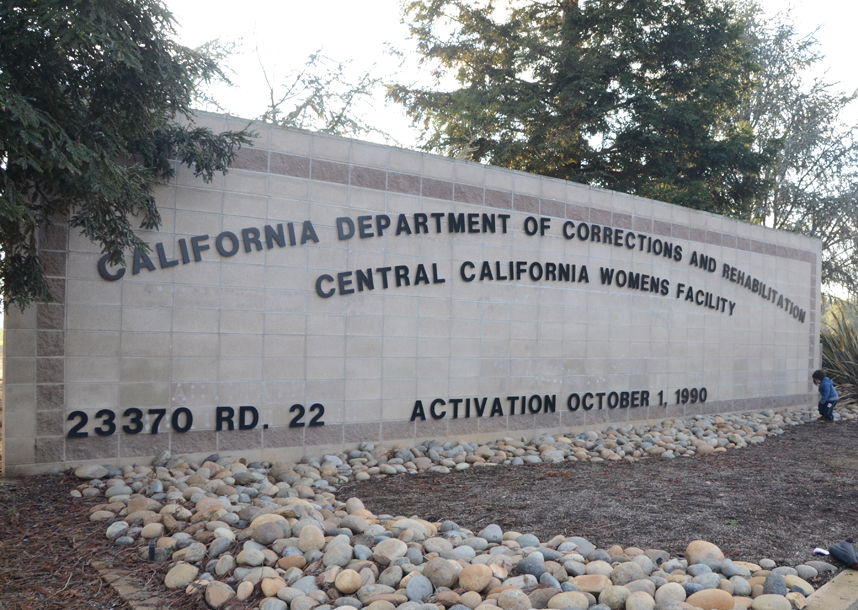

The prevalence of physical abuse may be the most open secret behind the growing number of women who end up behind bars. The Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, Calif., is the largest women’s prison in the country. (Daniel Arauz / CC 2.0)

The Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, Calif., is the largest women’s prison in the country. (Daniel Arauz / CC 2.0)

When Susan Burton and I walked up the concrete steps of the neat stucco bungalow on a sunny, palm tree-lined street in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood, nothing indicated the concentration of pain, heartache, friendship and joy that we would find inside.

As we stepped into the front room, we met a buzz of activity.

In one corner, a tall, young woman with intricate tattoos cascading down her shoulder and arm skillfully added braided extensions to another woman’s hair. At a side table, a serious, bespectacled woman assisted an older woman, equally serious, in filling out forms. On the couch, three women in shorts and colorful tank tops cooed over baby photos.

They all looked up and greeted Burton warmly as we passed through. “Hello, Ms. Burton.” “How ya doin’, Ms. Burton?”

She paused at each group, introduced me as her guest, and with a deep chuckle added her own sweet comment on the baby pictures. Everyone, it seemed, had something they wanted to tell her.

The bedrooms were tidy, the beds made up with colorful quilts, some decorated with embroidered pillows, stuffed animals and dolls. The tops of the dressers were crowded with toiletries—shampoos, hair gels, skin creams and makeup.

“In prison, these beauty products are an indication of your assets—they are all you can have, so when you have a lot, you want to show them off,” Burton explained.

The house is home to eight women, all of whom have served time in California jails and prisons. It is one of five houses in Watts that Burton runs for A New Way of Life, a program she started in 1998, only two years after she herself was released from prison. She started with one small cottage, purchased with money she earned from working multiple jobs as a home health aide, and with the assistance of her nephew, who had a good job, good credit and no criminal record to impede his signing for the mortgage. She furnished it with five sets of Ikea bunk beds, and asked the men from her 12-step program to help her assemble them.

To find women who could benefit from A New Way of Life, Burton would go down to the bus station around the corner from skid row. “I didn’t know who’d be getting off the bus, but I knew that, every day, women released from prison were on it. I showed up there because I wished someone had been there for me. Sometimes I saw a familiar face get off the bus, someone I’d served time with. I’d tell them, ‘I have a house in L.A., there’s a bed for you if you want it. It’s drug- and alcohol-free. You don’t have to go back to the streets if you don’t want to.’ ”

Lisa James, at 52 a bus driver and writer—her play “Freedom from Bondage” was performed by life-sentence prisoners at Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, the largest women’s prison in the country—is one of the women Burton welcomed. James’ warm smile, elegant, braided hairdo and welcoming demeanor belie the rough life she has endured. “When I went from the prison gate to the Greyhound bus station, I had no idea where I was going to go. I had burned all my bridges. I called a friend to take me to a 12-step meeting, because I knew I had to stay clean and sober. I didn’t want to go back where I came from. I told them, ‘I just got out of prison today.’ ”

Someone gave her Burton’s number. She called, and Burton invited her to stay.

“I had to tell her that I had no money, and she responded, ‘Did I ask you for money?’ ” James recalled.

History of Violence

Behind the cheer and camaraderie inside the small house in Watts are sorrowful memories etched as indelibly as the residents’ tattoos. Like the vast majority of incarcerated women, most of the residents were victims of physical and sexual abuse, some from a very young age.

Tiffany Johnson, 48, served 16 years for killing the man who had abused her since she was 5. “When I went to prison, I was warned not to talk to anyone—and I didn’t for many years. When I finally started opening up, I realized that I wasn’t alone. So many other women and girls have been through the same thing—you don’t tell anyone about these secrets.”

The prevalence of physical abuse may be the most open secret behind the growing incarceration of women. Ann Cammett, associate dean of the law school at City University of New York, has developed innovative programs in several states for women facing the challenges of reentry in the age of mass incarceration. “I rarely had a client who had not been a victim of physical or sexual abuse,” Cammett told me. “When I started interviewing women in prison, [every person] had a history of violence in their lives.”

The statistics, though scant, bear out Cammett’s observations. The last Department of Justice report, from 1999, documented that more than half of incarcerated women had suffered physical or sexual abuse. When I asked the DOJ spokeswoman for an update, she told me there is no more recent national study. All she could provide were academic studies of populations limited by geography and other factors.

Sue Osthoff, director and co-founder of the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women, co-authored a survey of those studies, which show that the figure is as high as 90 percent, and even this, Osthoff charges, undercounts the number of abuse victims who are still in prison. “Do we really need to verify a reality that we already know?” she asks.

Nexus of Abuse and Incarceration

Cammett asserts that violence against women increases their risk of being incarcerated. African-American and Latina women are at a higher risk both of physical abuse and incarceration, especially in the war-on-drugs era, when law enforcement focus disproportionately on communities of color.

The numerous pathways from victimization to incarceration are complex.

First, there are the direct crimes: Like Tiffany Johnson, a woman may physically attack an abuser to protect herself or her children. Johnson stabbed the man who had sexually assaulted her as a child when she became terrified that he would start molesting her 5-year-old niece.

But there are also indirect routes.

When a young girl is abused at home, she often will run away. Now homeless, she may seek shelter and security from a man who promises he will provide for her—and then forces her into prostitution and continues the abuse.

Lisa James describes how she fell into that trap: “We found ourselves trying to overcome mental abuse that was so evil and so dark. We just attached ourselves to someone, trying to find some form of affection, which just didn’t exist.”

In addition, a woman’s dire situation may lead to severe depression, and she will self-medicate with drugs or alcohol to cope.

Plunged into poverty and with no income, she will turn to crimes of survival—such as shoplifting, theft and the sex trade.

Susan Burton’s experiences followed that downward spiral. At 15, she was raped and later gave birth to her daughter. The former honor student dropped out of school and ran away from home. Alone and penniless, she soon found herself in the clutches of a man who thrust her into the world of prostitution and drug dealing. It cast a shadow over her life for decades.

Some abusive partners exert their control by threatening to use the legal system against the women. James relates her experience. “The guy that I was with, a white man, called me ‘nigger,’ told me I was no good, and constantly humiliated me. When I tried to leave him, he retaliated. He actually told my probation officer, ‘You need to make an example of her. Just throw her in prison.’ ”

Dramatic Rise in the Number of Female Prisoners

The huge rise in the numbers of female prisoners means their stories can no longer be ignored. In 1980, there were 15,000 women in state prisons around the country. By 2014, that number had risen to 106,232, a growth rate of more than 700 percent. If women in city and county jails are included, the number rises to 215,332—a third of all female prisoners in the world. Most are locked up for nonviolent crimes. Two-thirds of them have children under 18.

The toll is especially harsh for African-American women. Though drug use and dealing occur at similar rates across racial and ethnic lines, black women are more than twice as likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses as white women. According to The Sentencing Project, the lifetime likelihood that a white woman will be imprisoned is 1 in 118. For black women, it is 1 in 19.

What Is to Be Done?

If it is so clear that violence perpetuated against women and girls increases their risk of arrest and incarceration, what measures have been taken to break the cycle? The quest for solutions has been challenging—and not without pitfalls.

One landmark victory was the passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, after a long and arduous campaign by tenacious advocates in the domestic violence community. That pioneering federal law greatly enhanced the resources for investigation and criminal penalties for assaults against women, including intimate-partner violence.

According to Leni Marin, a former senior vice president of Futures Without Violence who worked primarily with immigrant women, “The turning point came when society recognized that domestic violence is not a private issue but a social problem.

“Once the abusive behavior is criminalized in the public sphere, then the legal system has to become involved,” she says.

Yet Marin is quick to point out the contradictions. “We know that racism permeates the criminal justice system, and we were well aware of some of the harmful impact, especially in communities of color.” Marin noted that consequences for immigrant women can be even harsher, as a woman’s abuser may have control over her legal status in this country.

“The enhancement of legal intervention after the passage of [the Violence Against Women Act] worked well for some people, but not for many others,” Osthoff notes,

“A lot of people who live in communities of color rightfully ask, ‘Why are so many resources going into the criminal justice system?’ They see an overemphasis on criminal legal responses—protective orders, arrests, imprisonment—yet that is often not what victims want,” she says.

Cammett notes, “We have a history in this country—in both civil and religious law—of allowing violence against women. When the women’s movement insisted that we needed to change this, we as a society criminalized the problem, rather than dealing with the underlying issues.

“In reality,” she says, “we live in a complex web of violence—with the military, law enforcement, gangs. But the law doesn’t have the capacity to deal with those complexities, so we separate people into victims and perpetrators.

“These are the constraints of law combined with a failure of imagination,” Cammett says.

She warns that along with the growth of awareness about domestic violence, there also must be awareness of the toll that a racialized criminal justice system takes on the communities most affected by violence. Though domestic violence cuts across all class and racial lines, the impact is felt most acutely in communities of color.

Burton sees the consequences of this contradiction every day. “All the recourses have such harsh consequences that people don’t accept them. Say you take the problem to your school, the school automatically calls the police. There is so much disruption for the family when the police come into play.

“We need services that are not law enforcement. Otherwise, this trauma over decades turns into substance abuse, people react irrationally—choosing fight or flight—and they, in turn, are criminalized, sometimes for very serious offenses.”

Cherri Allison, director of the Alameda County Family Justice Center in Oakland, Calif., understands the dichotomy well. “As an African-American woman who grew up in Oakland, I know what they are talking about,” she said. She brings a wealth of experience: As an attorney she represented both victims of domestic violence through the Family Violence Law Center and helped craft state legislation to address violence faced by women prisoners, including a prohibition on the shackling of women giving birth in prison.

Allison points to another law that went into effect this year, one that allows victims of human trafficking who have been arrested or convicted in juvenile court for any nonviolent crime to have their records vacated, sealed and destroyed.

Echoing Burton’s concerns, she explains: “A lot of our clients are afraid to call police. The police might take their children, they might call Child Protective Services and the children would be removed.”

But Allison also sees it from another perspective. “Police officers have told me they might come to the same house six or seven times before a woman can be persuaded to leave. They see little kids traumatized, shivering in the corner, and they don’t feel right leaving them there.”

The Alameda County Family Justice Center has partnerships with a dozen social service, health, counseling and job training organizations—a combination of government agencies and nonprofits all housed under one roof. Unlike Burton’s homey cottages, it is a large government building, a former medical facility. Colorful, handmade quilts, children’s artwork and origami cranes temper the institutional feel. Because it comes under the auspices of the district attorney’s office, the center has the resources to provide wraparound services to the 10,000 women and girls who come through each year—from teen victims of sex trafficking to older women being trained in computer programming.

Leni Marin’s organization, Futures Without Violence, also has collaborated with government actors, creating training programs for police and judges about intimate-partner violence. “We aimed to create a culture that does not tolerate domestic violence and implement procedures that recognize how complex this is,” she says.

Another pivotal state intervention was the passage of a unique California law in 2002 that allows some women who are incarcerated for crimes relating to their experience of abuse to seek a new trial and present expert testimony on domestic violence. One of the groups that lobbied for its passage was Convicted Women Against Abuse, survivors of domestic violence at the Chowchilla facility, who organized a legislative hearing inside the prison to highlight their experiences. After its passage, the group helped get the word out to other prisons and connected incarcerated women with volunteer attorneys to represent them. To date, California is the only state with such a law, although others, including New York, are considering one.

Osthoff warns that domestic violence advocates should not underestimate the shared traumatic experience of women who have been incarcerated. “If battering is about threats and control, think of how that is replicated in prison: the use of violence, intimidation, rules that change all the time, punishments that don’t fit the crime. The whole experience of incarceration is brutal.

“We spend more time, energy and resources on incarceration than on support services. Why are we putting women in institutions that replicate their experiences of abuse?”

Osthoff says that it is only by listening to affected women that we can come up with innovative programs and additional ways to support them outside of the legal system.

Cammett agrees. “Peer initiatives will be most successful. After all, who understands this better than those who have been through both domestic violence and the criminal justice system?”

Burton’s work epitomizes that challenge. In addition to providing housing and other services, she realized that helping individual women would not be enough to mitigate the racism and unfairness most experienced in the system. She successfully advocated for legislation to make broader changes, including “Ban the Box,” which makes it easier for people who have been convicted of a crime to find work, and Proposition 47, which allows for the retroactive reduction of certain felonies to misdemeanors and the expungement of criminal records.

Burton’s most recent initiative, Women Organized for Justice and Opportunity (WOJO), trains formerly incarcerated women to become activists in movements for social justice, including registering people in jails to vote. When she watches women from WOJO making phone calls to get out the vote, Burton says, “Many were still on parole and did not themselves have the right to vote. This, I realized, was a new type of underground railroad.”

An incident outside Burton’s A New Way of Life house is emblematic of just how many hazards there are on this journey. A group of residents is helping another resident, a young Asian-American woman in khaki shorts and a pink polo shirt who is moving out, carry her belongings to a white station wagon parked in the driveway. They load up a duffel bag, several shopping bags filled with baby clothes, a pink backpack and a jumbo size box of Pampers Newborn.

One woman cuddles a tiny baby, only a few months old—the departing resident’s child. Her friends give her hugs and small farewell tokens—a nosegay of cloth violets, a box of chocolates, a baby’s bib.

Burton approaches the group but does not join in the gaiety. I watch her gaze—she is eyeing the grim, stocky man in a starched, button-down shirt standing impatiently on the driver’s side of the car.

She wishes the young woman well, and then walks me back into the cool shelter of the house.

“She shouldn’t be going back to him,” she says, shaking her head. “He’s a military man, and he controls her by force. She’s going right back into violence and abuse.”

Inside the house, several women approach Burton to talk about an upcoming leadership training session, eager to show her various schedules and plans.

Tiffany Johnson spent almost two decades behind bars, and had to go before the parole board four times before she was granted her release and permission to take the spot Burton offered her at a New Way of Life. Today, she is the associate director there. “Now I look at my life as a healing process, for me and for the little girl [I used to be, who] was abused and terrified, and I tell other women that they are not alone,” Johnson says.

Elaine Elinson is the former communications director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California and prize-winning coauthor of “Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California.”

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.