Living in a Renter’s Republic

Why vote to save democracy if it can't save the roof over your head? Signs for apartment rentals in Glenview, Ill., on Jan. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Signs for apartment rentals in Glenview, Ill., on Jan. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Not long after the shock came the questioning and finger-pointing. Was Kamala Harris’s defeat by Donald Trump caused by excess wokeness? A paucity of liberal podcasters? Insurmountable sexism and racism? Joe Biden’s hubris? His and Harris’ facilitation of Israel’s genocide in Gaza? Inflation? Disinformation? The mind reels at the scope of Democratic failures. The makeup of Trump’s newly broadened base — the former and future president swept every swing state and made big gains across deep-blue states and cities — was no less impressive. Most discussed has been the swing of young people, people of color and low-income voters away from Democrats toward Trump, where they voted at all. The more diverse a county, the more it shifted toward Trump; counties with the highest share of Black, Latino or low-income voters also saw the steepest drops in turnout. Nationwide, voters with household incomes under $100,000 split roughly evenly between the candidates, a blow to the Democrats and a coup for the right.

A month since the election, this already familiar narrative of class and party dealignment seems clear enough. Yet a major connecting thread between these groups remains underacknowledged: All are more likely than not to rent their homes, and therefore to suffer under the all-time-high rent burdens, rising precarity and deteriorating conditions that afflict the nation’s rental housing stock. Indeed, the counties that saw the largest vote shift toward Trump were those with the toughest housing markets — where inventory is constricted and home prices have far outpaced average incomes. The working-class dealignment could just as aptly be called a tenant dealignment.

Just over a third of all Americans are tenants, and the proportion is growing. Renter households are increasing at triple the rate of homeowners. They are disproportionately young and non-white: over half of Black and Latino households rent, as well as roughly two-thirds of Americans under the age of 35. The median renter household income is $47,000. Nationally, rents are up more than 23 percent since Biden took office, the sharpest four-year increase on record. More than half of renter households — over 22 million — are rent-burdened, meaning they pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent and utilities, and 1-in-5 report severe rent burden, paying more than 50 percent. These, too, are record numbers, and rates are even higher for Black, Latino and young tenants, who are also most likely to live in substandard conditions, with absent or inadequate repairs, heat, hot water or electricity.

The failure to adequately address the housing crisis exemplifies the fecklessness that doomed Harris’ campaign.

The despair goes deeper. Almost a quarter of renters report skipping meals to make their monthly rent payments. The expiration of pandemic-era tenant protections and rental assistance programs — which Biden and congressional Democrats did nothing to prevent — has caused evictions to spike back to pre-COVID levels. Homelessness is at an all-time high. Wider economic discontent can also be connected to housing. An astonishing 75 percent of swing-state voters said housing costs were the most stressful economic issue for their families, and nearly two-thirds said housing unaffordability made them feel negatively about the economy. Rent remains the single largest factor keeping inflation high, accounting for half the overall increase in inflation as recently as September.

Even non-renters grasp the severity of the situation. One recent real estate industry survey found more than 80 percent of Americans support capping rents. Another poll showed 70 percent of swing state voters were more likely to vote for candidates who backed rent controls. No such candidate appeared, of course — least of all Trump, America’s most famous landlord. But in this context, it’s hardly shocking that counties with the highest cost of living moved most toward Trump despite voters with the highest incomes shifting decisively for Harris. Why vote for a candidate promising to save democracy if you don’t believe they can save the roof over your head?

In a majority-homeowner nation, the rental crisis alone cannot explain Harris’ defeat, especially since the concentration of renters in cities means that as a group they probably still tilted toward her. But the demographic overlap between tenants and those who moved away from Harris cannot be ignored. Moreover, the failure to adequately address the housing crisis exemplifies the fecklessness that doomed Harris’ campaign. Any effort to challenge Trump and the reactionary forces he spearheads must not make the same mistake.

* * *

To her credit, Harris raised the profile of renter issues compared to previous elections. But it’s not difficult to understand why a struggling tenant might still have opted to stay in their (too-expensive) home on Election Day. Her housing proposals openly embraced market-driven YIMBYism, centering on tax breaks for developers in a bid to bring down rents over time by juicing the construction of 3 million new homes. Whatever its policy merits, the push failed to bring those it aimed to help to the polls. Like Biden’s green industrial policy, Harris’ housing plan responded to an urgent crisis with reforms whose benefits would be felt slowly, if at all. As a former member of Biden’s National Economic Council tweeted following the election, “I strongly support investments in additional housing supply. But you can’t tell a room full of renters facing 25% rent hikes that our solution is more supply that will bring down rents a few years from now. What was our message to those renters?”

Harris’ message was a convoluted mix of punitive and progressive. She touted a plan that would grant down-payment assistance of up to $25,000 for first-time homebuyers — but excluded anyone who had failed to pay rent on time in the previous two years. Biden’s own proposals were no less muddled. Addressing the NAACP Convention in mid-July, during the final throes of his campaign, Biden mumbled about a proposal, never before mentioned, to cap annual rent increases at $55: a bungled rollout of the administration’s rather less ambitious plan, announced the same day, to cap rent hikes at 5 percent on large corporate landlords.

When Harris took the reins less than a week later, she talked up the rent cap plan at rallies, receiving massive applause. For a time, things looked promising. At the Democratic National Convention in August, progressive advocates made a presentation to party insiders and Harris delegates arguing that renters were an untapped left-leaning voter pool capable of deciding the election. They armed the campaign with polling showing swing-state voters were far more likely to vote for a candidate pushing rent caps; without such a platform, those renters were 20 percent less likely than homeowners to vote at all.

But when the Harris campaign finally published an “Issues” page online in early September, the rent cap policy had disappeared. Harris never mentioned it again on the campaign trail. As with Tim Walz’s early attack on “weird” MAGA Republicans, any confrontational edge was sanded away. For the Harris campaign, “bipartisanship” meant holding flashy rallies with Liz Cheney, not championing policies that could win supermajority-level support from voters in both parties.

Harris’ message was a convoluted mix of punitive and progressive.

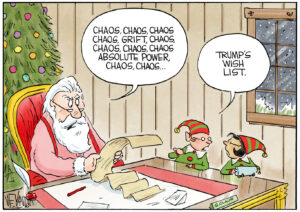

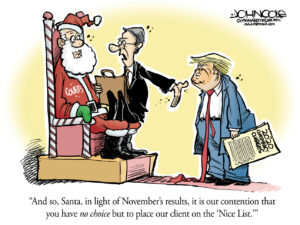

Trump, a third-generation landlord and developer, of course offered nothing in the way of rent relief or other pro-tenant policies. Like Harris, he gestured toward incentivizing new construction and slashing regulation. He sometimes mentioned using federal land to develop so-called “freedom cities” replete with flying cars — an idea about as realistic as Harris’ impenetrably means-tested blueprints, but at least more memorable.

Above all, what Trump delivered that Harris didn’t was a complete narrative, one that at least acknowledged hardship and named villains, however unjustly. As usual, the blame fell on immigrants. Trump seized on a bizarre video of armed men knocking on an apartment door in Aurora, Colorado, who Trump claimed were members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua who had taken control of the housing complex. Local residents, police and elected officials all denied that gangs controlled the complex, whose squalid conditions were instead the fault of the management company, which was being sued by the city of Aurora for creating uninhabitable conditions, including roach infestations, crumbling walls and uncollected trash. Undeterred, Trump vowed to launch what he called Operation Aurora, “the largest mass deportation in American history,” in the Denver suburb on Day One of his presidency.

While in keeping with the Trump’s constant attacks on immigrants, the episode was also an effort to capitalize on widespread tenant misery. He promoted another fraudulent account of Venezuelan gang members taking over a building in Chicago, and JD Vance later blamed rising housing costs in Springfield, Ohio, on the Haitian immigrants whom he and Trump also baselessly accused of eating cats and dogs. Trump ran online ads with pictures of heavily tattooed Latino men, implied to be gang members, behind the text, “Your new apartment managers if Kamala’s re-elected.” These attacks fed xenophobic bigotry, but they also opened a novel channel for the anger and despair that so many renters feel about their homes. Voters know someone must be to blame for decrepit and costly housing.

Whom did Harris blame? The housing shortage alone, while real, is hardly a compelling antagonist. In her stump speeches, Harris made the occasional promise to crack down on algorithmic rent-fixing, but how could the fine print of technical proposals compete with Trump’s crude drama, splashed across the internet and national TV? The Harris campaign also tended to muffle its own strongest messages. An ad called “Paycheck,” created by the Democratic super PAC Future Forward, directly called out high rents and promised to lower costs by increasing supply and “cracking down on landlords who are charging too much.” In mid-October, Future Forward contacted Harris’ campaign with viewer surveys showing that the ad had performed in the 100th percentile, the most effective of the race. Yet the campaign ignored it, according to the New York Times, and in the end the ad was seen by almost no one. Post-election polling showed that even though 72 percent of voters supported prosecuting corporate landlords, just 19 percent were aware the Biden-Harris administration had actually attempted a limited version of this with its antitrust action against RealPage, the algorithmic rent-setting platform. To reach masses of disengaged or misinformed voters, it’s not enough to offer a grab bag of indirect or limited policies, in lieu of a basic, compelling story. Tenants’ frustration needs somewhere to go.

* * *

I work as a tenant organizer in New York City. Not infrequently over the past few years, I’ve heard low- and middle-income tenants living in poor conditions vent resentment at new migrants who are supposedly being lavished with credit cards and quality subsidized housing. These frustrations have been voiced by everyone from Caribbean immigrants in Brownsville, Brooklyn, to longtime Latino tenants in gentrified Hell’s Kitchen, to white tenants on the bourgeois Upper West Side. Many organizers and tenant lawyers I know have heard some version of these complaints, which predate Eric Adams’ election and the city’s so-called “migrant crisis,” let alone this year’s presidential campaign. Even more tenants report deep skepticism toward politics and politicians altogether.

It’s not that these tenants don’t blame their landlords for high rents and poor living conditions — they do. But they also feel a deep bitterness at the state’s utter failure to protect them from abuse. “Landlords are going to do what landlords do,” one tenant told me, but government should at least be expected to serve its citizens. The task of tenant organizing is to redirect renters’ anger, opening up the possibility that landlord malfeasance is not inevitable and can be changed by tenants’ own collective action — through rallies, rent strikes, bad press, pressuring lenders to cut off business and whatever other tactic suits a specific campaign. Government may or may not come along for the ride.

If there is hope for the Democrats — a party about as awash in real estate money as the Republicans — it lies downstream from work like this, with tenants taking matters into their own hands, leaving no opportunity for donor meddling or consultant bungling. Today only a tiny fraction of the nation’s 100-million-odd renters belong to a tenants’ union or other organized group. But the latter’s ranks have grown rapidly, especially since the pandemic, and the seeds of a more powerful, national tenants’ bloc are being nurtured.

The Tenant Union Federation represents one such effort. Calling itself “a union of unions,” TUF comprises existing tenant groups in Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Montana and Connecticut. The organization is the first real attempt to build and wield tenant power on the federal level in 40 years. In October, TUF launched the first ever nationally coordinated rent strike, targeting federally financed properties, which total about 12 million units nationwide. Like a labor union, TUF tactically deployed organizers to launch rent strikes in ten of these buildings, largely in areas with little history of tenant organizing, such as Ypsilanti, Michigan; Charleston, South Carolina; and Bozeman, Montana.

Government should at least be expected to serve its citizens.

Their demands are multipronged. Landlords must make repairs and agree to rent caps; the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, must push to attach rent caps to the $150 billion of financing they offer landlords every year. Tenants, brought in through campaigns in their own buildings, are recruited to join the union, bringing more power to other local fights. Elected officials, meanwhile, can get on board or get out of the way. In Kansas City, they’ve chosen to get on board, in what is now, after almost two months, the longest rent strike in city history. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, D-Mo., hardly a progressive champion, has been pushed to advocate on behalf of the tenants federally; the FHFA, for its part, has authorized $1.35 million for immediate repairs. Tenants, however, are refusing to back down until they secure rent caps.

To win what is needed on a national scale, tenants must replicate this fight over and over, while adapting strategically to local conditions. The battle over housing, which is subject to a bramble of local, state and federal regulations, must be waged and coordinated across each of these levels. It’s crucial that precarious renters in Missouri, Kentucky and Montana be connected with those in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

In a nation where the rights and interests of landlords and homeowners predominate, that fight will not be easy; even when united, tenants are not a majority. Critics could also point out that in California, a proposition to repeal a state ban on rent control recently failed for the third time since 2018. But so did a bill to raise the minimum wage, while similar efforts won in Alaska and Missouri. What matters is how these demands — like minimum-wage raises, or rent control, or building social housing — are fought for: who is cast as the villain, who is organized into support and opposition, and how a basic but potent narrative is spun. To mobilize a critical mass of people, these fights must be seen not as one of left versus right, or even of progressives versus moderates, but of those below versus those above, those who control the housing of others, and those who don’t control their own.

This is not a language most Democrats are comfortable speaking, and the party’s sprint toward wealthy support does not suggest a willingness to try. Already, a chorus of party-hack postmortems have suggested simply parroting Trump’s bigotry on social issues, with little to say about the economic populism that might discomfit the Democrats’ increasingly affluent base. Yet for many new Trump voters in the multiracial working class, bigotry was not a draw, but something to be stomached in hopes of material security. It certainly wasn’t a positive for the millions of eligible voters who sat the election out altogether. The choice between building power from below and lapsing into inaction, despair and resentment is not one that can be left to liberals. In a “nation of homeowners” that is more and more a nation of renters, a future majority must organize itself and let Democrats decide what side of the math they want to stand on.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.