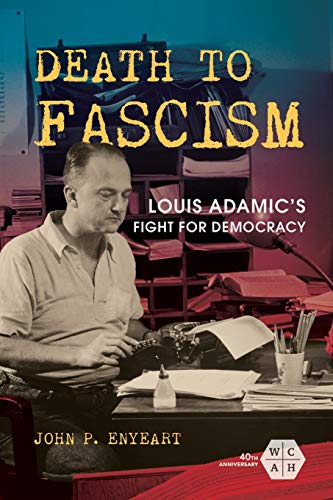

Louis Adamic’s Life Fighting Fascism

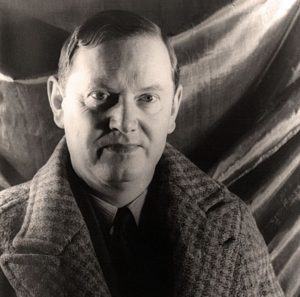

A new biography of the Slovenian journalist reminds us that reviving American democracy will take more than the rise of minority elites. Journalist Louis Adamic. (Digital Library of Slovenia / Wikimedia Commons)

Journalist Louis Adamic. (Digital Library of Slovenia / Wikimedia Commons)

Louis Adamic, a popular nonfiction writer of the 1920s-40s, never escaped—perhaps never wished to escape—his status as an enigma. He was a talented journalist whose work appeared in a variety of magazines, as well as the author of well-received works of fiction and nonfiction. He was also a Slovene immigrant, from that sliver of land once part of Yugoslavia and now an independent state. He poured his finest energies into the vision of a multicultural, multiracial American democracy, something not seen then—or now. Adamic also seemed early on to be an existentialist or grim pessimist, projecting images of fatalism and a propensity for violence as the inescapable reality of his new country. In the end, he threw himself into a crusade against the incoming Cold War, and was assassinated for his trouble. His death removed one more political inconvenience from the latest version of American liberalism.

John P. Enyeart, a professor and chair of the history department at Bucknell University, has written a new biography of Adamic; Enyeart knows his subject intimately and passionately. He gives us a clue in the book’s very title: “Death to Fascism: Louis Adamic’s Fight for Democracy.” Fascism is no longer old news. Nor is well-financed support of fascist or semi-fascist authoritarian leaders, bathed in religious fundamentalism. If American democracy is to be revived, Enyeart shows us through the study of Adamic’s life that it must mean more than tolerance and the rise of minority elites.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Death to Fascism” at Google Books.

Ironically, Adamic’s best-known book, “Dynamite” (1931), was the one destined to be least understood. A nonfiction investigation of the mystery around the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910, it could hardly convey how political controversy and outright repression, following the explosion, wiped out a vibrant local socialist campaign that seemed likely to win the mayoralty, or that the consequence dealt a decisive blow to the Southern California left for perhaps two decades. Socialists (and later communists) defended the accused bombers, the McNamara brothers, as victims of the class struggle. Adamic insisted that he discovered evidence proving their guilt.

“Dynamite” was widely believed, on publication, to be a vindication of law and order, almost a justification of the anti-Bolshevik, anti-labor (as well as deeply racist) wave that began in wartime and continued into the great Red Scare of 1919-21. But Adamic insisted, against his critics, that he wanted to inspire the American middle class to improve the condition of working people, and that the guilt or innocence of the McNamaras had not been the deeper philosophical theme of his book. Rather, he was addressing the American propensity for violent resolution of social dilemmas.

Enyeart explains that Adamic, a working journalist struggling for a living and a reputation, was inclined to exaggerate his own research and fudge his conclusions. This is useful information when placed alongside his writings on Slovenia and the South Slavs (including Croatians and Serbians). His “Laughing in the Jungle” (1932), in part a recollection of his childhood in Austria-dominated Slovenia, was a surprise hit. The book appealed to Americans to overcome the nativist prejudice against immigrants, especially the “new immigrants” from Southern and Eastern Europe, who by this time dominated the workforce of many industries and populated the urban zones of cities like Cleveland and Chicago.

Adamic also took up the somber task of fighting the fascism that was swooping over his homeland. There, as he explained after an extended visit and the completion of “The Native’s Return” (1934), severe repression had set in—cultural and well as political—with the banning of the Slovenian language in schools.

Unwilling to be pigeonholed as a leftist, Adamic chose not to associate himself directly with the Slovenian socialists in the U.S., then numbering tens of thousands and influential beyond their numbers in the labor movement. His portrayal of the alienation and exploitation of immigrants found readers among assimilated Americans who, in the Depression era, also felt excluded and oppressed.

Befriended by luminaries like novelist Upton Sinclair and Nation magazine editor Carey McWilliams, Adamic gained status as an independent radical, just in time for the high tide of the New Deal and its uncertain partner, the Popular Front. His popular novel, “Grandsons” (1935), urged a nonrevolutionary socialism at the moment when communists themselves took on new roles, especially within the rising industrial union movement soon known as the Congress of Industrial Organizations. For Adamic, the CIO was the very acme of anti-fascism, and with his rhetoric, he placed himself as the spokesman for a wider sentiment.

Enyeart insists that by the later 1930s, Adamic helped redefine the popular understanding of pluralism as the very definition of Americanism. He launched a magazine, Common Ground, to urge fuller democracy at home along with solidarity for the victory of democracy abroad. Most crucially, this also meant racial democracy, a subject broached with extreme caution outside of the left. Anti-fascism, he insisted, meant anti-racism and nothing less. Adamic was surely a godsend for the large, educated middle class of magazine-reading liberals eager to advance the Roosevelt program, and who were outraged at the attempts by conservatives to justify racial barriers and anti-Semitism. He was also extremely popular in ethnic communities. And as Enyeart shows, the logic of anti-fascism carried Adamic toward anti-imperialism.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the German assault upon Europe placed Adamic perfectly to popularize the broader implications of anti-fascism. He visited the White House at Eleanor Roosevelt’s invitation—actually sharing a meal with the first family and Winston Churchill.

His campaign became still more personal as right-wing South Slavs in the United States embraced fascism, usually in the name of defending Christianity. Powerful progressives, including New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, embraced the other side—the Partisans—in Yugoslavia, Adamic’s home territory dominated by avowed communist Josef Broz Tito.

Then the war ended and the tide turned. Adamic was attacked along with his hero, former Vice President Henry Wallace, as subversives, enemies of American democracy, and communists, even if they insisted otherwise. Adamic was not pro-communist but definitely accepted the presence of communists within a wider social movement. Suddenly, his liberal audience faded away or was driven into silence. A large and now-forgotten movement, the American Slav Congress, which looked to Adamic as a visionary, disappeared in the Cold War wave. His last show, so to speak, was heroic support for the Progressive Party campaign of 1948. His 1950 book, “The Eagle and the Roots,” an appeal against the rightward drift, seemed to fall upon deaf ears. No one knows exactly how Adamic died in 1951, but suspicions turn toward fascist agents of anti-Tito forces.

Enyeart writes with special passion about the investigating committees, congressional hearings, “friendly” witnesses, and trumped up charges that opened space for the far right. Adamic himself was accused of being a personal agent of Stalin—just as Tito broke with the Russians, and American communist leaders warned against the rise of “Titoism” within the party. The “fight for democracy” in the book’s subtitle was by that time losing heavily, too often through the unwillingness of liberals to resist, or the flocking of liberals, like former Hollywood progressive Ronald Reagan, to the conservative side. When Adamic’s beloved CIO was hit by the Taft-Hartley Act and the most aggressive unions found themselves expelled, labor’s engine of social progress went into a stall from which it has never quite recovered.

Enyeart turns in his last chapter to Adamic’s legacy and anti-fascism today. If fascism, or something very much like it, is back, then so is a widening sense of democracy as either all-inclusive or so diminished as to be useless in modern times. We cannot be sure what Adamic would have thought of today’s world. But his perception that the United States is a violent nation, and that anti-fascism and the labor movement, linked to anti-racist movements, could turn the tide—well, these are awfully pertinent ideas.

Your support is crucial…

With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.