‘Lyrics From Lockdown’ Creator on Using Art as a Wake-Up Call

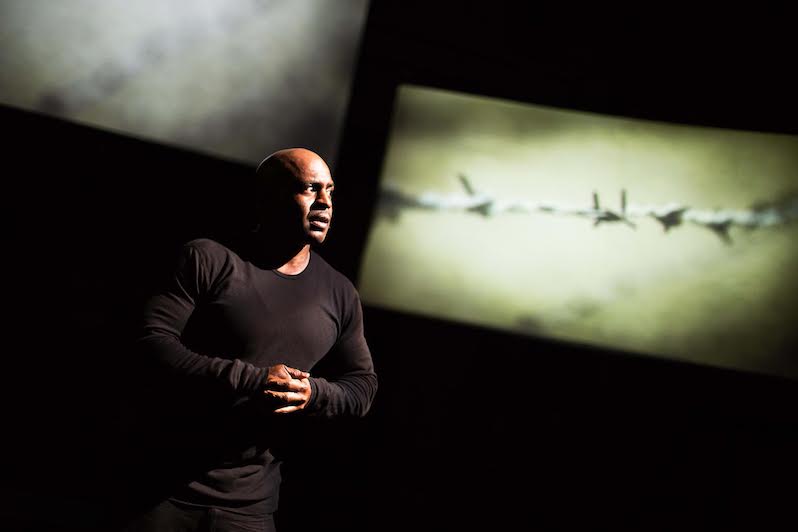

Playwright Bryonn Bain, who turned his own harrowing experiences into a one-man dramatic production, joins director Gina Belafonte for a Truthdig interview.

On an autumn night in 1999, Bryonn Bain, his brother and his cousin left a Harlem nightclub and stopped at a bodega a block away. They purchased some items and exited the store to discover several men, one of them standing in an open car door, throwing things at a window above the store. Glass shattered and people on the sidewalk scattered to avoid being hit by shards. As Bain and the two other men headed up the street, they saw the car pull away.

Before the three of them could reach a nearby subway station, bouncers from the nightclub—suspecting them of having broken the window—ordered them to stop. In his second year at Harvard Law School at the time, Bain knew his rights, so he and his relatives kept walking. At that point, the bouncers forcibly attempted to stop them. When police arrived, the bouncers pointed at the three black men, who were taken into custody immediately. After four court appearances over five months, the case against Bryonn Bain, Kristofer Bain and Kyle Vazquez was dismissed. No evidence was ever produced to support the charges against them.

Two weeks after Bain’s run-in with the law, his law professor, Lani Guinier, asked her students to write about an injustice in their own lives. Bain cut and pasted what he had already written in his poetry journal. Guinier recommended he try to get it published. When “Walking While Black” ran in the Village Voice in 2000, it went viral before the age of social media and led to Bain being interviewed by Mike Wallace on “60 Minutes.”

In 2002, when Bain was pulled over on the Bruckner Expressway in New York City for a faulty taillight, a routine check revealed a warrant for his arrest on felony grand larceny charges and two misdemeanors. Bain spent three days in holding cells, without being told the charges against him. He met with a legal-aid attorney who, upon hearing his list of academic credentials, disbelieved him and said he probably was delusional.

After a man was arrested at Columbia University carrying Bain’s ID, an identity theft investigation led to dismissal of charges against Bain. Bain sued the New York Police Department and won.

These are the main incidents behind “Lyrics From Lockdown,” Bain’s one-man, multimedia account of his twisted journey through the legal system. The show, which received critical acclaim for its premiere last year, is in revival at The Actors’ Gang in Culver City, Calif., playing now through Feb. 25.

Bain currently teaches African-American studies at UCLA, after teaching in a variety of settings from Harvard and Columbia universities to Brooklyn’s Boys Town detention center and Rikers Island, New York City’s main jail complex.

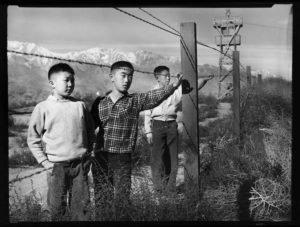

He is reviving “Lyrics From Lockdown” to bring attention to the millions of minority inmates warehoused in the prison-industrial complex, including fellow activist Nanon Williams, who was sentenced to death as a juvenile and is now serving life for a crime he didn’t commit. (Ballistic evidence that came after the conviction showed the bullets were fired not from Williams’ .25-caliber gun but from the .22-caliber gun of his accomplice.)

For the revival, Bain found a like-minded director in Gina Belafonte. A longtime social justice advocate, she serves as co-director and content producer for Sankofa.org, an organization that links celebrities with grass-roots organizations dedicated to giving voice to the voiceless. She is the daughter of Sankofa’s founder, actor/activist Harry Belafonte.

Here, Bain and Gina Belafonte tell Truthdig about the shame of mass incarceration and what they see as theater’s role in resisting “the coup” in Washington.

You thought your story was too common to resonate with readers before Ms. Guinier encouraged you to publish. Why do you think it struck a chord with readers?

Bryonn Bain: The reason the story resonated with folks, not just black folks but white folks from New Jersey to New Zealand, [was because] they said, “Thank God you’re saying this, cause we say the same thing but no one believes us. But [you have credibility] because of the elite education you have, the pedigree.” My mom says, “You have the same degrees as Barack Obama, plus one. How come he ended up in the White House and you ended up in the jailhouse?” I said it’s a sign of the times. This is what’s happening. People have been deluded until this last election, thinking we’re living in a post-racial era when in fact we have more black men in prison now than ever before in human history, more people in prison now than ever before in human history. So we can’t be fooled by the symbols of progress into thinking that we have arrived.

Jeff Sessions has a history of racially inflammatory remarks and is on record as pro-privatization of prisons.

Gina Belafonte: Those who want to support private prisons, we have to create strategies where doing business with those people becomes uncomfortable for them.

BB: What’s happening right now in Washington is a reminder of the roots of genocide and slavery, which are as much a part of the founding of the country as the ideas of democracy and liberty and equality. And it’s easier to deal with one than it is with the other. It’s easier to talk about the virtues this country is founded on and not deal with vices. But they go hand in hand. So you see little cause for optimism going forward.

BB: The optimistic side of it is for coalitions to emerge that otherwise might not have emerged. It’s forcing multiracial coalitions, progressive coalitions and folks who are on the fence about whether they need to take action against this coup in Washington. This Trump and Pence and Bannon coup is inspiring coalition-building in ways that would not otherwise be possible without their instigation.

Trump supporters would say he won the election and is doing exactly what he promised during the campaign.

BB: Donald Trump won this election because of an electoral college system that is rooted in the politics of plantation slavery, when this country agreed that black people were less than human, they were three-fifths of a human being. Because of that assumption, that legal mandate of black inhumanity, of black folks being less than human beings by the law of the land. Because of that, we have a system [in which], by the hand of the police and police abuse, by the hands of the mass incarceration complex, and even by the hand of a political system, which actually puts people in power who represent less than a majority vote, we systematically dehumanize these folks.

Talk about that—giving voice to people who are marginalized.

BB: It’s critical. This movement is about humanizing people who have been systematically dehumanized. That’s what the civil rights movement was about; that’s what the Black Power movement was about; that’s what the immigration struggle is about, that’s what the gay rights movement is about; that’s what Black Lives Matter is about, that’s what the Dreamers are about. These movements for social justice are about getting justice for people who have not only been treated in an unjust way but have been dehumanized systematically. It’s easy to treat people like garbage when you look at them as less than human.

GB: Any opportunity we have as artists to educate our community and engage them in public discourse around issues that are facing those that are voiceless or disenfranchised [creates] an obligation to do so.

Do theater and the arts in general have a responsibility in the Trump era?

GB: Certain artists have an in-kind opportunity to lend their services to organizations on issues they believe in. Not every artist is going to pump a Black Power fist and create a poster and a sign or a march. But I do feel like all art is political. I can only hope that artists aim, in their personal vision, to shine a light wherever or on whatever.

BB: Artistic work is aesthetics. So if anesthesia is about putting you to sleep, aesthetics is about waking you up. I think art is about waking ourselves up, waking up parts of our humanity that have fallen asleep, or are dead—or waking up other folks who realize the humanity of folks that are being dehumanized. That’s one of the most powerful tools that art can have. It can be many things. It can be a tool for healing; it can be a weapon; it can be the tip of the spear; it can be many things. Art is being an alarm clock right now to wake us up to the reality of what’s happening and the urgent need for us to actually come together and take action to stop the direction the country, and ultimately the world, is moving toward in the hands of those who’ve risen to power.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.