#MeToo Writings Are About a Lot More Than Stories

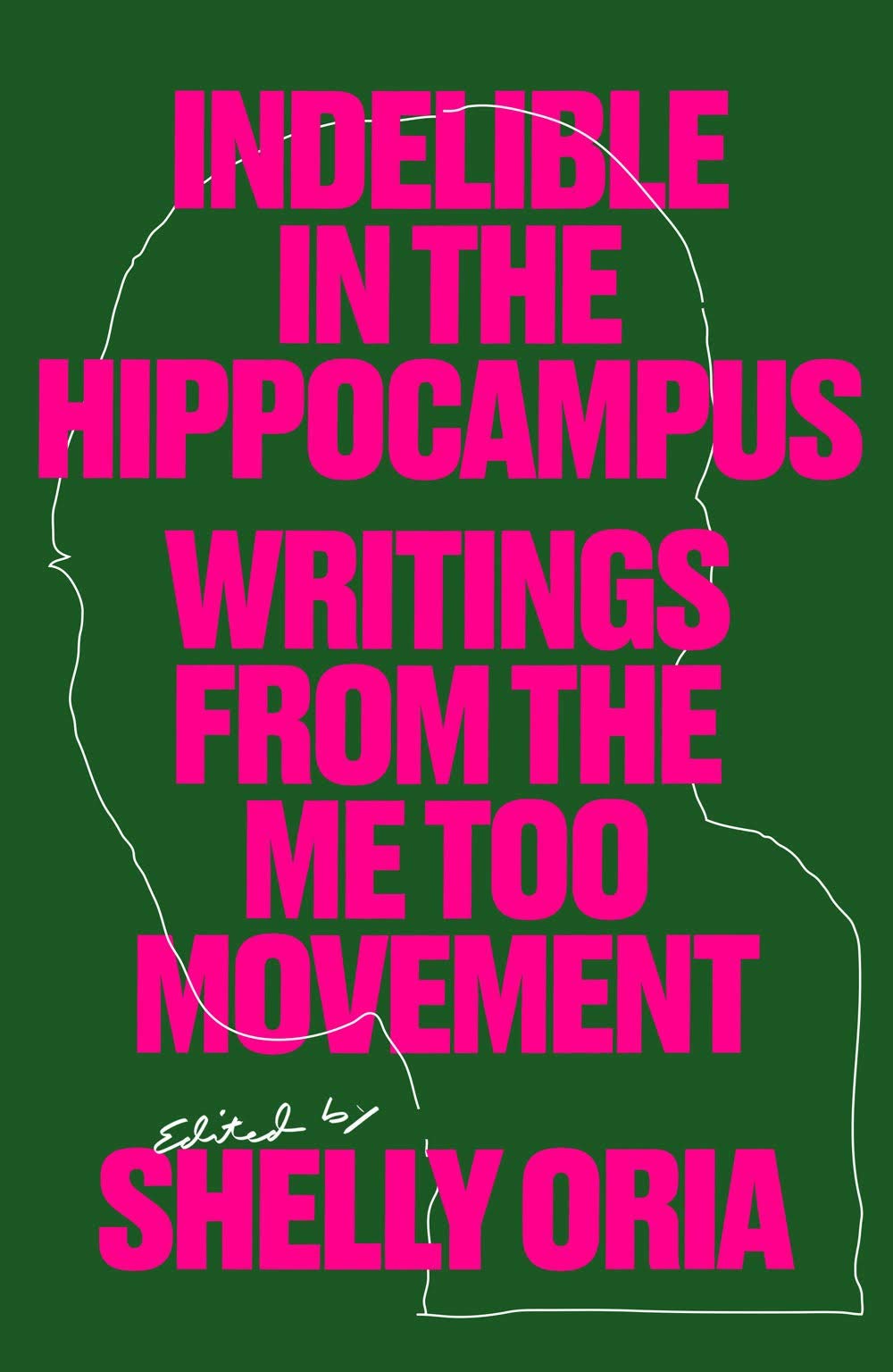

A new book’s relentless archive of victims’ stories also functions as alternative police reports, convictions and, in one case, executions. Shelly Oria's book title comes from a quote from Christine Blasey Ford's senate testimony. (Win McNamee / AP)

Shelly Oria's book title comes from a quote from Christine Blasey Ford's senate testimony. (Win McNamee / AP)

“Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings From the Me Too Movement”

A book edited by Shelly Oria

“Indelible: Writings From the Me Too Movement” is not just a collection of nonfiction essays, short stories, and poems about the Great Reckoning edited by award-winning novelist Shelly Oria. “Indelible”’s writings also strive to create a forum for litigating sexual violence claims outside of the failed state. In a society where only one out of four rapes are reported — often because victims understand that police are unlikely to believe the allegations of accusers who do not resemble the “real rape victim” archetype — the book’s relentless archive of victims’ stories also functions as a series of alternative police reports, witness statements, prosecutorial complaints, convictions, and, in one case, executions.

“Indelible: Writings From the Me Too Movement” is not just a collection of nonfiction essays, short stories, and poems about the Great Reckoning edited by award-winning novelist Shelly Oria. “Indelible”’s writings also strive to create a forum for litigating sexual violence claims outside of the failed state. In a society where only one out of four rapes are reported — often because victims understand that police are unlikely to believe the allegations of accusers who do not resemble the “real rape victim” archetype — the book’s relentless archive of victims’ stories also functions as a series of alternative police reports, witness statements, prosecutorial complaints, convictions, and, in one case, executions.

“When I was seven, a teenage relative showed me his dick twitching in his jeans […] [but my guardian kept] the assault secret,” begins writer and musician Jolie Holland in the numbly denunciative essay “What Does ‘Forgiveness’ Mean?” She goes on:

When I was nine, my stepparent’s brother tried to take off my pants. I didn’t tell anyone because there was no one to trust. At the age of twelve, a substitute teacher asked if I had a boyfriend and acted surprised when I said I didn’t. […] When I was thirteen […] [my doctor] made snide sexual comments to me. My mother said nothing about it. […] About the same time, a teenage neighbor boy sent my legal guardian a letter telling her he was jerking off at my bedroom window. […] As far as I know, [she did not act on this information.] On another occasion, a strange man cornered me while I was walking through my neighborhood in the evening and held a gun to my head. […] [I never told] any adults what had happened.

Holland is not the only writer in “Indelible” to construct her essay as a dual-function evidentiary exhibit and multiple-count indictment. But her contribution helps to set the tone for the book as a whole. It also highlights the mental “trials” that other women find themselves privately enduring after experiencing assaults, a process that often lasts their entire lives.

“Indelible in the Hippocampus,” of course, takes its title from Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony against now-sitting Justice Brett Kavanaugh, wherein Dr. Ford accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her at a party in the 1980s, when she was 15 years old and he was 17. Ford acknowledged that she never reported the attack to her parents or any authority, in part because she “was too afraid and ashamed to tell anyone the details.” In lieu of a police report, a witness, or a video that could verify the attack, Dr. Ford could only offer her memories of Kavanaugh “push[ing her] onto the bed and […] running his hands over [her] body and grinding his hips into [her]” as proof of Kavanaugh’s crime. Her use of the term “indelible” sought to impress upon her interlocutors the permanent heft those memories imposed upon her psyche (the hippocampus is involved with processing long-term memory), so they would understand that her recall was as tangible a piece of evidence as something physical — a gun, a stained dress, scars. But the majority of the Senate did not see her memory that way, or simply didn’t care whether she was telling the truth or not.

“Indelible in the Hippocampus” shows us that memory is what most women retain of their rapes, assaults, and harassments. These recollections form the cornerstone of a legal proceeding that they must plead and contest in their imaginations in place of an official prosecution. When the state fails women and other victims of sexual violence by not believing them and not filing charges against their attackers, these victims must undergo DIY mental trials in an effort to resolve their traumas with any measure of justice. This psychological process involves reporting the offense to oneself or another person, naming it as a cognizable crime, establishing fault, and conceiving of a proper punishment.

In novelist Kaitlyn Greenidge’s “Your Story Is Yours,” Greenidge affirms that the decision of whether and how to report remains firmly in the hands of the victim: “[N]o one is entitled to your story. You can tell it or not tell it.” But, in “How Did It All Begin?” poet and essayist Syreeta McFadden clarifies that race will shape the decision to speak out. Sometimes a woman of color may decline to say anything because her attacker is of her same minority race, and the victim may “fear[] for him.” On other occasions, women of color may stay quiet because they know they are more likely to be disbelieved, as historically, “Black women were not to be afforded protection or humanity.”

In “Bye, Baby,” memoirist Melissa Febos teaches us that even “small” sexual invasions can count as serious wrongdoing that affect a survivor’s larger life. In this story, a sixth-grade girl is accosted in the bathroom by an adult man named Vega. The episode seems to only take a few seconds, but to her it feels like death: “I can feel the outline of his body in the aura of its warmth. Its heat is an image reflected on me. My body could wither in an instant, extinguished, a streak of smoke in the air. […] I know I will never tell anyone about this.” Similarly, in “Hot for Teacher,” essayist Courtney Zoffness reveals how seemingly minor incidents (“Maybe I was overreacting”) can connect in survivors’ minds to past offenses, a phenomenon that increases the events’ felt severity. Zoffness recalls how a student in her creative writing class read out loud a first-person narrative about how he “could and would push aside the pile of ungraded papers and take her passionately atop her desk.” Zoffness’s resulting “confusion/fury” spurs her to contemplate the then-recent Virginia Tech massacre and a time when she was involuntarily digitally penetrated in a dance club.

In the story “Glad Past Words,” professor and writer Mecca Jamilah Sullivan reveals how concepts like consent, desire, and even the mandate for “fresh reporting” are slippery when it comes to sexual harm. In this short fiction, 17-year-old Shaniece, having recently shed so much baby fat that she can now “almost pass for a video dancer,” has sex with her best friend’s father. At first, the encounter doesn’t read like rape or another variant of sexual assault, as “[t]here was no no and there was no yes, and what there was was feeling, but if you asked her what the feelings were, she probably couldn’t tell you, which didn’t matter anyway ‘cause it’s not like anyone asked.” But later, as Shaniece observes herself, she realizes that something bad has happened to her. “She found it hard to focus on even simple things […] soon it became a problem. […] It messed with her, messed her up. […] There was no one she could talk to about this.”

In Caitlin Delohery’s blindingly frightening “Lakes,” the writer/editor tries to tell the story of how she was sexually used by her cousin, Danny, who later shot his girlfriend to death in 2006. “Lakes” confronts the reader with the problems of memory and details how, even if a survivor doesn’t recall an assault with the kind of clarity that Dr. Ford exhibited (to no avail) at the 2018 hearings, that doesn’t mean that a rape did not occur. Delohery seeks to understand what Danny did to her without any assistance from the justice system that abandoned her and her cousin’s other’s victim. Bereft of support and protection, she must name the abuse herself through the painful work of writing it down:

I can’t draw you a diagram of what my cousin did to me a couple decades before he killed a woman. I can’t name all of what I saw or was made to touch or do or accept. I can’t tell you how many years it went on, list the number of times. I can’t tell you how my kid body responded, recoiled, or how it didn’t. Often, the clearest way I can understand myself, now, at thirty-seven, at twenty-seven when I first started writing this story, and at four years old, when I think this story began for me, is to remind myself, aloud or in writing, just: something happened.

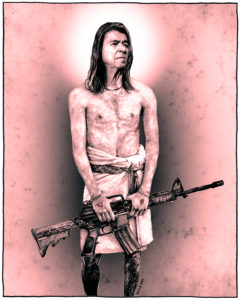

With “But We Will Win,” Oria closes the book with an incendiary piece of fiction that finalizes the essays’ metaphorical prosecutions with a sentencing and punishment phase. Part Charlize Theron in “Monster,” and part social justice crusader à la the Women’s March, Oria tells the story of an unnamed protagonist whose former love, Roxie, was killed when driven into traffic by a sexual harasser. The hero responds first by distributing pamphlets and then beating an innocent white man to death, a murder that her current girlfriend covers up by burning her clothes (then they have sex). “But We Will Win” is a freaky document of rage — even in its surrealism, it makes a very large claim of what kinds of retributive action are warranted in response to a whole human history of the sexual exploitation of women and other vulnerable people.

It’s worth noting that the death penalty is not permitted for the crime of rape of an adult woman in the United States, as per the 1977 Supreme Court decision Coker v. Georgia. Even if it were, it would be unequally imposed, and, in any system, Oria’s protagonist has committed an unwarranted, cold-blooded murder. I am sympathetic to the feelings of ferocity limned in “But We Will Win,” but the story doesn’t really stand with the rest of the collection, whose authors take a clear-eyed view of the cascades of sex crimes withstood in silence. Nevertheless, in an age when justice is withheld by racist and sexist organs of government and pursued through unreliable social media canceling, the question of punishment is real and immediate, and one that we desperately need to think through.

Together, the works assembled in “Indelible in the Hippocampus” offer us the complex products of the state’s neglect to deter and prosecute sexual violence. A common misconception of survivors of sexual assault and harassment is that their emotional responses are disjointed and muddled, which is why the concept of “rape trauma syndrome” (RTS) was developed in the first place. RTS is a diagnosis of a rape victim’s post-trauma that is often used in rape trials to explain why victims act “counterintuitively” — for example, when they don’t immediately report, or when they can’t describe their assaults in ways that the police or prosecutors find sufficiently coherent. One of the key strengths of the book is that it reveals how survivors’ silence and supposed confusion are rational responses to an uncaring power structure that requires sexual assaults to bear certain rigid hallmarks, such as a clear “no,” or some evidence of physical force. The writers in “Indelible” prove that where the government (and patriarchy) sees only disorganized emotionality in a victim’s response, she may actually be engaged in a sophisticated psychological process that charges, prosecutes, deliberates, and even punishes her attacker. The tragedy is that she is all too often forced to do this by herself, and only within her own imagination, because our criminal justice system has failed her.

This article originally appeared on the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.