Miss America: Why Racism Thrives Online

The danger of online racism is that people seem to get away with it and public disapproval in the form of reports like this one do not appear to have the same effect in lessening racist speech as disapproval does in face-to-face encounters.The danger of online racism is that people seem to get away with it and public disapproval is less effective.

Some things evolve and some things don’t. Such is the case with this weekend’s wins of Nina Davuluri and Floyd Mayweather and the tsunami of racism that overtook Twitter in response.

Ladies first. Nina Davuluri is the second consecutive New Yorker to be crowned Miss America and the first Indian-American to win the title. Though Davuluri’s platform was “Celebrating Diversity Through Cultural Competency,” like all of us she is more than the sum of her racial and ethnic identities.

According to CNN, “the 24-year-old Fayetteville, New York, native was on the dean’s list and earned the Michigan Merit Award and National Honor Society nods while studying at the University of Michigan, where she graduated with a degree in brain behavior and cognitive science.” Her goal is to become a physician. Davuluri plans to invest her time as Miss America working with the U.S. Department of Education as an advocate for science, technology, engineering and mathematics. These are fields where women, regardless of racial or ethnic background, are sorely underrepresented.

Davuluri’s feel-good story took a racist turn in the Twitterverse, where some were outraged by the fact that 2014’s Miss America isn’t white. As in 2010, when the Lebanese-American beauty queen Rima Fakih was crowned Miss USA, racism was expressed not just explicitly in the form of tweets, but also in the level of ignorance those tweets exposed. For example, Jezebel reports that some tweeps seemed confused over whether the new Miss America was Indian-American, Arab, Muslim or Latina. They could all agree, however, that she didn’t deserve the title based on whom they thought she was.

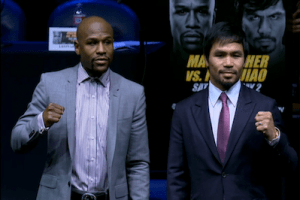

Something similar happened to African-American boxer Floyd Mayweather after he won Saturday night’s fight against Mexican fighter Canelo Alvarez. Mayweather first caused a stir on Twitter when he entered the ring alongside Lil’ Wayne and Justin Bieber. Many wondered whether Mayweather and his team accessorized with the stars because of their social media reach into different racial communities. But that meme was nothing compared with the outpouring of racist epithets tweeps typed in response to Mayweather’s amazing win. According to a report from Latino Rebels, online bigots concluded that Mayweather didn’t win because of his talent, skill and training. Rather, he won because he is black and that’s definitely not a characteristic to be praised, from a racist point of view.

Although reports are right to highlight and challenge these expressions of online racism, particularly in this weekend’s cases, the tone of surprise is a bit misleading. Ebony’s Jamilah Lemieux had said it seems as if “the Internet just met the Internet” in recent weeks and that by now we shouldn’t be shocked by online racism. Lemieux is right. Online racism is entirely consistent with offline racism and demographic shifts.

For instance, the number of U.S. hate groups has more than doubled in the last 10 years, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, up to 1,007 active hate groups in the United States in 2012. Deborah Lauter, civil rights director for the Anti-Defamation League, has said that thousands of hate websites are live, “more than we can possibly keep track of.” Survey research indicates that the rise in active hate groups is correlated with census projections stating that white people will no longer be the U.S. racial majority by 2042. The hate surges online when achievements by people of color are noted and interpreted as taking away something to which a white person “should be” entitled. So people like Davuluri and Mayweather become targets because they represent demographic change and new opportunities for people of color, while challenging stereotypes about who Americans are and what they can achieve.

Racist ignorance in virtual spaces may often be misspelled and factually incorrect, but it should be taken seriously because its effects on the recipient can be powerful. According to a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health by Dr. Brendesha Tynes, a professor of Education at USC, of 264 Midwestern high school students, approximately 20 percent of whites, 29 percent of blacks and 42 percent of “other” or multiple races reported being personally subjected to racial epithets or other discrimination online. These young people were more likely to become depressed, anxious and, possibly, less successful academically. What’s more is the effect on race talk in general. The danger of online racism is that people seem to get away with it and public disapproval in the form of reports like this one do not appear to have the same effect in lessening racist speech as disapproval does in face-to-face encounters. For evidence of this, check out the many YouTube testimonials from online gamers via the Gambit Hate Speech Project by MIT-Singapore Game Lab.

The Internet we have is not the safe space it was promised to be. But the good news is that we can do something about it. As digital citizens we can make the Internet safer. We can engage in self-reflection and deal with criticism from others in a way that makes real race talk possible. That’s means fighting racism with truth about who we are and how the world is really changing. After all, racism 2.0 is not a foregone conclusion. We, the people, have made it seem that way. And we have the power to make it different.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.