|

To see long excerpts from “The Annotated Christmas Carol” at Google Books, click here.

|

“The Annotated Christmas Carol”

A book by Charles Dickens, edited and with notes by Michael Patrick Hearn and illustrated by John Leech

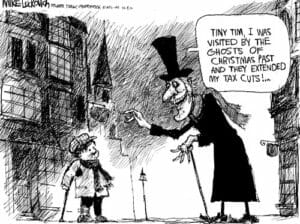

“Bah, humbug!” says Ebenezer Scrooge about Christmas — but some readers would use the same phrase to dismiss “A Christmas Carol” itself. One critic described Charles Dickens’ famous book as “saturated with exaggerated Christmas fervour” and “larded with soggy and indigestible lumps of sickly sentiment.” That’s probably a little too strong, too dismissive for this artistically complex tale about a skinflint’s change of heart. Over the next few days, many families will again watch Alastair Sim or the Muppets in one of the innumerable film adaptations. Yet will they ever open the book? All too commonly, “A Christmas Carol,” like “Don Quixote” and “Robinson Crusoe,” is a classic people think they know without actually ever having read a word of it.

Michael Patrick Hearn’s excellent annotated edition, which first appeared in 1976, has been reissued this year (though without any updating since its last appearance in 2004; the bibliography is noticeably out of date). Hearn — best known as an authority on children’s literature and on “The Wizard of Oz” in particular — provides a substantial introduction in which he tracks Dickens’ early career up through his 1842 visit to America and the composition of “A Christmas Carol” that followed in 1843. Hearn points out that the young novelist drew upon the depiction of Yuletide festivities in Washington Irving’s underappreciated “Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon” and took his “conversion” plot from “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton,” part of the wonderful “Christmas at Dingley Dell” section of his own “Pickwick Papers.”

In tracking the critical reception of “A Christmas Carol,” Hearn quotes extensively, almost relentlessly, from reviews both positive and negative. Somewhat unexpectedly, he also appends a brilliant, fact-filled afterword about Dickens’ celebrated one-man shows, in which the novelist read — actually performed — a shortened version of “A Christmas Carol” (which this annotated edition reprints in an appendix). On his U.S. tour alone, Dickens acted out the story of Ebenezer Scrooge 76 times between Dec. 2, 1867, and April 10, 1868.

The point of an “annotated” edition of any classic is to supply readers with information, with the definitions and illustrations and facts that will help deepen our appreciation or understanding. Hearn’s first substantial note cites Dickens’ brief preface to a collected edition of his “Christmas Books” — these include “The Chimes” and “The Cricket on the Hearth,” as well as “A Christmas Carol” — wherein their author defines each of them as “a whimsical kind of masque,” aiming to awaken “loving and forbearing thoughts.”

A masque? A masque is a Renaissance court entertainment, a ballet-like pageant, in which the actors sing and dance, and allegory abounds. English majors will remember that in John Milton’s “Comus” — probably literature’s best-known masque — a debauched satyr-like godling kidnaps a virtuous “Lady,” then urges her to surrender to the pleasures of the flesh. In effect, Milton outwardly represents the never-ending inner struggle — the formal term is psychomachia — between reason and the appetites. In this instance, chastity triumphs.

“A Christmas Carol” is utterly masque-like, replete with allegorical figures (including those two demonic children, Ignorance and Want), full of singing and dancing (Fezziwig’s party, Fred’s Christmas games, the Cratchit family’s pitiful caroling), and resolutely focused on thawing the cold heart of Ebenezer Scrooge through a series of dramatic tableaux. This is one reason why the story works so well on the stage and screen. There’s no interiority to speak of; it’s all visual spectacle, often maudlin and almost operatic, with a dying Tiny Tim instead of a dying Mimi.

Rereading “A Christmas Carol” this December, I was again struck by the religious, even sacrilegious, motifs running through this redemption parable. Note, for example, the pervasive symbolism of darkness and illumination, of shadows and light. That oddly sexless child, the Ghost of Christmas Past, turns out to be a kind of candle, while the Ghost of Christmas Present holds a torch that bathes the world in holiday brightness and benevolence; but the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a hooded Death-like phantom in black. Scrooge is invariably drawn to the light — of Fezziwig’s festivities, Fred’s boisterous party, the brightness of his own parlor when transformed into a Yuletide version of Aladdin’s cave, and even to a lonely fire in a pawnshop’s brazier.

More subtly, there exists a swirling undercurrent of biblical imagery. Like Jesus murmuring “noli me tangere” to Mary Magdalene, Marley warns Scrooge not to touch him. Sentences such as “Rise and walk with me” convey a New Testament resonance. Fezziwig, according to Scrooge, possesses a God-like power “to render us happy or unhappy; to make our service light or burdensome.” When Belle releases Ebenezer from their engagement, she tells him she has been replaced by a golden idol. And while the three raggedy creatures who enter the pawnshop obviously recall the witches in “Macbeth,” they also flickeringly suggest three wise men bearing gifts to a stable and Roman soldiers casting lots for the dead Christ’s robe.The Ghost of Christmas Present is particularly perplexing. He may be based on Father Christmas, with hints of Old King Cole, but why is he so gargantuan? Could this be an allusion to medieval iconography that represents Christ as a giant? Why does the Ghost bare his chest, a gesture that recalls the many images of the Sacred Heart? Scrooge even speaks to him of all that has “been done in your name.” Strangest of all, when the Ghost shakes his torch over quarrelsome people, it somehow throws off drops of water, and their mood immediately changes to one of good fellowship. How can one fail to think of a priest with an aspergillum sprinkling holy water?

Traditional lore tells us that the dead are allowed to walk the earth again on Christmas Eve. Dickens uses this conceit not just to bring Marley to Scrooge, but also to present a vision of the damned:

“The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.”

Here are no torments by devils with pitchforks: Hell is wanting to do good and being unable to! Was this Dickens’ own idea? It’s positively Augustinian.

This year, try reading instead of watching “A Christmas Carol,” and pay attention to its unsettling elements: the hovering phantom-like narrator, Scrooge’s recurrent facetiousness, the religious peek-a-boo, its apolitical, even reactionary views on social change. There’s more to this Dickens classic than just a progress from “Bah, humbug!” to “God bless us, every one!”

Michael Dirda reviews books weekly for The Washington Post.

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.