No-Man’s-Land: The Writing and Art of Guantánamo

A new book examines how art produced in Guantánamo reimagines empathy and resistance. In this 2021 photo reviewed by U.S. military officials, a flag flies at half-staff at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba in honor of the U.S. service members and other victims killed in the terrorist attack in Kabul, Afghanistan. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

In this 2021 photo reviewed by U.S. military officials, a flag flies at half-staff at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba in honor of the U.S. service members and other victims killed in the terrorist attack in Kabul, Afghanistan. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Esther Whitfield’s new book, “A New No-Man’s-Land: Writing and Art at Guantánamo, Cuba,” is profoundly poetic and ethically resonant. The work opens with an unusual expression of gratitude for “iguanas, cats, banana rats, hummingbirds, the sea, and woodpeckers” by Mansoor Adayfi, a writer, advocate and former detainee who spent 14 years imprisoned at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp. Through these creatures, Adayfi found a way to navigate the disorienting and painful reality of prolonged imprisonment, drawing solace and resilience from the natural world around him.

Throughout Whitfield’s book, she addresses the enduring question of art’s role in confronting atrocities, including the stripping of an innocent man’s freedom in the name of the war on terror. Whitfield’s analyses of borderland writing, visual art and documentaries by people who live in the province of Guantánamo, Cuba, and by prisoners in the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base U.S. detention camp reveal unexpected continuities and slippages in experiences of repression, suggesting that these ostensibly “enemy” forces share a common drive for discipline and, above all else, control.

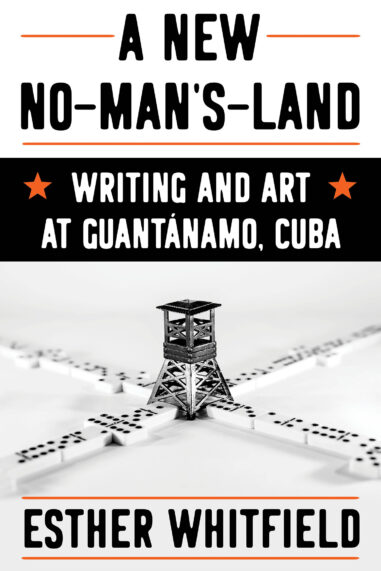

The book’s structure explores this question through an ecocentric lens, juxtaposing contrasting perspectives of hegemony while interweaving creative expressions of this borderland. As such, it sets forth a compelling model for how to conceive of the role of literature not “after” barbarity, to reflect upon the theorizing of German philosopher and musicologist Theodor Adorno, but within it, having to negotiate sometimes contradictory positions of so-called progress that are always predicated upon repression. Whitfield’s book dismantles any notion of separation of the so-called local and global spheres from the outset with cover art by the Guantánamo-born artist Alexander Beatón titled “Para que la verdad sea creíble tiene que ser vigilada” (For the Truth To Be Credible It Has To Be Guarded), an apt phrase for addressing the mirage that constitutes ideology. The image, featured in a 2021 exhibit by the artist, displays a guard tower in the center of a game of dominos, underscoring how everyday Cuban activity is conditioned by the presence of repressive apparatuses, whether attached to the Cuban state or U.S. imperialism.

Whitfield’s book provides a new vision for a global, cosmopolitan political feeling — one that defies conventional notions of empire, authoritarianism or their discontents — by enacting a pragmatic and honest approach toward dialogue between diverse entities, each contributing some form of good, even if not all their actions are commendable. For example, while the Guantánamo base represents an obvious wrong, the Cuban revolutionary state’s vilification of its own migrants over the past 6 1/2 decades, even threatening to take away their citizenship, is another form of injustice also worthy of scrutiny and condemnation. Likewise, Cuban literature, whether produced on or off the island and labeled “dissident” by state forces, should not have its literary merit or testimonial value diminished on account of support it may receive from U.S. organizations with ideological positions that differ from our own. Whitfield’s critique demonstrates how these works can still serve as powerful testimonies to the Cuban state’s violence against its citizens.

This book is a compassionate exploration of human relationships forged in the most unlikely of places.

Whitfield goes to great lengths to create a singular and comprehensive textual and visual archive — one that, without her patient yet bold approach, could never have come into being. She demonstrates that “care” is not just an external concept reflected in the poetry, visual art and films she brings to light but is also deeply embedded in her approach to those who have endured violence. It is as if her critical method takes its cues from the detainees’ approaches to life. By focusing on acts of care, Whitfield engages in a methodology of care that helps her construct a transnational community through her research and translation project. More than just a critical work, this book is a compassionate exploration of human relationships forged in the most unlikely of places.

We learn how Moroccan-born Ahmed Errachidi expressed care for his fellow inmates by conjuring up imaginary feasts evoking food and invitations to his home in Morocco through words pronounced from one cell to another. This gesture is echoed in one of the book’s most moving moments, when Whitfield recounts a conversation about empathy between Errachidi and Cuban poet José Ramón Sánchez Leyva at a conference at the University of Graz in Austria. Whitfield and Katerina Gonzalez Seligmann’s translation of Sánchez Leyva’s “The Black Arrow” has made the poet’s profoundly empathetic, cross-cultural verse accessible not only to Spanish poetry readers, but also to former detainees whose suffering Sánchez Leyva captures so poignantly. Whitfield quotes Errachidi’s confession in Austria that Sánchez Leyva’s poetry has led him to reexamine his own years of detention, adding yet another layer of reflection to this cross-cultural encounter.

This book would have been groundbreaking even if it had focused solely on the cultural production of Cubans in the Guantánamo province. It challenges the prevailing tendency to position Havana at the center of Cuban literary discourse — an all-too-common bias in cultural scholarship on Cuba. In the concluding chapter, “Future,” Whitfield uncovers and juxtaposes materials rarely accessible beyond their local context, often preserved in the personal libraries of authors and editors. She brings together “El futuro” (1994-1996), a publication created by Cuban refugees held at Guantánamo as a result of the Balsero crisis, with “Porvenir” (2008-) from the dissident group Alianza Democrática Oriental, thoughtfully exploring the shared aspirations and tensions between Cuban refugees and dissidents. Whitfield then situates these within a broader constellation of future-oriented projects related to this “same” space, including the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, the Guantánamo Bay Museum of Art and History, and the volume “Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, and Reparations/Chicago to Guantánamo,” co-edited by Amber Ginsburg, Aaron Hughes, Aliya Hussain and Audrey Petty. Weaving together firsthand accounts of hardship with imagined visions of future restoration — whether as reparations or a marine reserve — is a bold move, one of many ambitious choices that define this text.

Prior to Whitfield’s work, few critics had examined the plight of Cubans who have sought asylum in Guantánamo at the U.S. base, aside from scholarship on the accounts of Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas. Whitfield’s examination of the “intricate and local network of intimacies” — where Guantánamo writers, artists and filmmakers including Sánchez Leyva, Ana Luz García Calzada, Roberto de Jesús Quiñones, Rolando Rodríguez Lobaina and Daniel Ross convey the anguish of vilified Others, those who aren’t meant to be “friends” on the global stage — is nothing short of remarkable. The nuanced maps that Whitfield construes frequently challenge the prescriptive visions of international solidarity that political discourse demands, compelling us to dig more deeply into the tangled web of complicity and resistance that pervades these expanding testimonies of repression. For instance, Whitfield’s observations about Cuban author García Calzada’s shift in perspective regarding Cuban migrants and border guards in the English translation of her 1995 collection “Heavy Rock” illuminate the ongoing challenges for a Cuban writer negotiating life under an authoritarian regime. In this way, Whitfield emphasizes those moments where García Calzada expresses genuine empathy for migrants seeking asylum in Guantánamo, but does not refrain from noting the complexity of García Calzada’s position. Specifically, in the introduction to the English translation of her stories, García Calzada also notes the perceived risk these migrants pose to others.

Whitfield’s maps extend beyond artists to include individuals who, despite not being creators themselves, forged affective bonds with those vilified Others, making hostile spaces more homelike. For instance, some U.S. guards converted to Islam, while others voiced their own antagonism toward U.S. racism and their sense of victimhood, even as their official roles as functionaries required them to remain on patrol. These are topics that Whitfield explores at length in one of the book’s most intriguing chapters, titled “Guards.”

Whitfield upholds a belief in the fluidity (rather than relativity) of meaning.

Some of Whitfield’s most incisive critical insights emerge in close readings, where she emphasizes the small yet redemptive acts of literary creation. A striking example is the author’s reflection on a line from Ibrahim al-Rubaish’s poem “Ode to the Sea,” reproduced in the text’s first chapter on translation: “Doesn’t Cuba, the vanquished, translate its stories for you?” Here, Whitfield meditates on the term “vanquished,” connecting it to Mohammed el Gharani’s “First Poem of My Life,” in which Cuba is described as “afflicted.” Translator Flagg Miller notes that the Arabic term for “afflicted” is mankuba. Whitfield deepens this analysis by situating these terms within Cuban revolutionary discourse, where “victory” has long been the dominant vision for Cuba’s future. By identifying and examining these subtle yet profound misalignments, Whitfield — true to her comparatist approach — highlights the importance of finding common ground across linguistic and cultural divides.

While repression and containment define the operations of hegemonic powers and bureaucracies, Whitfield upholds a belief in the fluidity (rather than relativity) of meaning — a central tenet of artistic practice. This becomes especially evident in her analysis of how Sánchez turns a detainee’s assessment brief into an intertextual poem, drawing on both translated Arabic literature and regional poetry. The result is a compelling argument for symbolic repair through creative production. Ultimately, “A New No-Man’s Land” is not just an academic work — it is a call to reimagine belonging, empathy and resistance in the face of overwhelming political forces.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.