‘Notes of a Native Song’: Writer James Baldwin’s Work Resonates in the Time of Trump

Musical artist Stew’s ode to the literary icon is particularly welcome now, when Baldwin's words have taken on fresh significance.

Musicians Mark “Stew” Stewart and Heidi Rodewald perform with The Negro Problem in “Notes of a Native Song.” (Stew & Heidi)

Singer-songwriter Stew (Mark Stewart, who goes just by Stew) was in grammar school when he first heard of author-activist James Baldwin. Just a boy, Stew vaguely understood the writer’s eloquent arguments for social justice, but in time Baldwin’s work had a profound effect on him. That’s why, when Harlem Stage commissioned him to contribute to its yearlong Baldwin celebration, Stew could not refuse.

The result was “Notes of a Native Song,” music inspired by Baldwin’s writings and performed by Stew, who is African-American, and co-composer Heidi Rodewald, along with the band The Negro Problem. Since its off-Broadway premiere in 2015, the reviews have been outstanding, and the duo is hoping for the same in Los Angeles at downtown’s REDCAT arts center, Dec. 14-17.

After Baldwin, also African-American, was refused service in a restaurant one day in 1948, he left his native New York and moved to Paris for 10 years. “My countrymen were my enemy,” was his conclusion, reached not just through his own personal experiences — like a childhood trip to the New York Public Library, where he was told by a cop, “This is no place for you” — but by witnessing the truth of it on a daily basis among his friends and neighbors on the streets of Harlem.

From his semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novel,“Go Tell It on the Mountain” to “The Fire Next Time,” Baldwin examined the impact of racism on the psyche and the simmering conflict between black and white America. His 1956 novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” explores sex and relationships — straight, bisexual and, Baldwin’s own orientation, gay. A return to the U.S. in 1957 marked a shift in both his work and his life toward promoting the Civil Rights Act and analyzing all it entails. “No Name in the Street” centers on the crusading triumvirate of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers, all friends of Baldwin’s, each assassinated.

“I think any time you talk about race in this country, people start to listen closer and people get a little uncomfortable,” Stew told Truthdig about the audience for his show, which features rock, jazz and rhythm and blues songs commenting on alienation, white supremacy, love and tolerance, interspersed with Stew’s own thematically aligned observations.

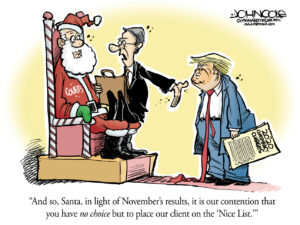

Since the election of Donald Trump, the show has taken on new meaning. According to Stew, many white people who used to observe but not experience alienation from the mainstream are now wondering where their liberal values fit into Trump’s America. “White people are beginning to understand what it’s like for the government to be against them. This Cabinet is against every fucking white person in this country that’s not rich,” said Stew. “It’s like, ‘Oh no, we feel under fire as well.’ It’s like, ‘Welcome to the feeling.’ It sucks that we’re here, but we’re all able to feel and see this thing.”

A songwriter from Los Angeles, Stew began recording with The Negro Problem in the 1990s and had two albums, “Guest Host” and “The Naked Dutch Painter and Other Songs,” named Entertainment Weekly’s album of the year in 2000. Still, he remained best known for “Gary’s Song,” which he wrote for TV’s “SpongeBob SquarePants.”

Things changed when he met Rodewald and undertook a work based on Stew’s creatively formative experience living in Amsterdam and Berlin, a Baldwin-inspired sojourn. “Passing Strange,” their rock musical about a young man’s journey of self-discovery in Europe, was nominated for seven Tony awards in 2008 and won for best book for a musical. “Notes of a Native Song” is Stew and Rodewald’s second collaboration. Rodewald was in The Negro Problem in the ’90s and has since collaborated on a number of pieces since 2008.

The depiction of minorities in popular media is a recurring theme in Baldwin’s writings. Through his work, he hoped to inspire change by drawing attention to incivilities that went unremarked upon in mainstream media. He inspired Stew and Rodewald who, through their music, hope to do the same — one reason why they remain optimistic, even in the age of Trump.

“The one good thing about this guy is he is making all of us realize how connected we actually not just are, but better be. If we’re going to get through this shit, the Balkanization and separation shit has to go,” Stew said, espousing Baldwin’s idea that blacks and whites need each other in order to make America work. “Trump is creating the new ’60s. I think it’s going to politicize people to a level we can’t even imagine. When you have somebody who makes Nixon look like Che Guevara, how asleep can people be? I do not think they’re going to sleep through this.”

Baldwin likened race relations in America to a dysfunctional love affair. Stew said he hopes the polarizing figure of Donald Trump will help us all realize how correct his idol was.

“I have to be optimistic and say we are going to get through this,” he said. “And I think and hope we’ll be more connected as a result.”

With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.