NYT Trans Health Coverage Defers to One Controversial Researcher

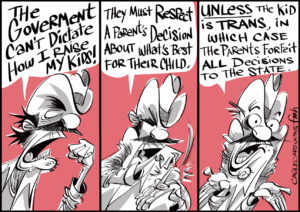

Giving outsize attention to Jamie Reed has led to distorted analysis of a sensitive issue. Graphic: Truthdig

Graphic: Truthdig

The New York Times has taken a lot of heat recently for its coverage of transgender issues. More than 370 current and former Times contributors signed an open letter detailing how the Times has covered trans issues with “an eerily familiar mix of pseudoscience and euphemistic, charged language.” The contributors emphasized the Times’ coverage of adolescent gender-affirming care, and detailed how its articles are being cited in court by states seeking to ban these treatments.

Though the Times’ immediate response was underwhelming, critics had hoped that the paper might take their criticisms to heart in future coverage. That hope was dashed when the Times doubled down with a nearly 6,000-word story about the unsubstantiated claims made by former Washington University in St. Louis gender clinic employee Jamie Reed.

The piece by Azeen Ghorayshi, headlined “How a Small Gender Clinic Landed in a Political Storm” (8/23/23), serves as a greatest-hits album of all of the Times’ problematic coverage on adolescent gender-affirming care, filled with familiar tropes and tactics the paper of record has used to distort the issue.

As in other Times stories on trans healthcare, a small number of detransitioners get a disproportionate amount of column space.

In February, Jamie Reed, a former employee of the Transgender Center at Washington University in St. Louis, wrote a first-person account for the Free Press (2/9/23), a media company run by former Times reporter Bari Weiss, who left the paper because she said it was censoring viewpoints that go against progressive orthodoxy. Reed accused the clinic of rushing kids into transition, and failing to properly inform them and their parents of the effects of hormone treatments. The same day, Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey announced an investigation into the clinic, and revealed that Reed had signed a sworn affidavit detailing her claims.

The St. Louis Post Dispatch (3/5/23) and the Missouri Independent (3/1/23) each interviewed dozens of adolescents and their parents whose accounts contradicted Reed’s claims about the center’s practices. Reed refused to be interviewed by either publication to discuss the discrepancies. Instead, she went to the New York Times, which was more than willing to frame her allegations in a positive light.

The Times uses a “both sides” framing to set up its story on Reed:

Ms. Reed’s claims thrust the clinic between warring factions. Missouri’s attorney general, a Republican, opened an investigation, and lawmakers in Missouri and other states trumpeted her allegations when they passed a slew of bans on gender treatments for minors. LGBTQ advocates have pointed to parents who disputed her account in local news reports, and to a Washington University investigation that determined her claims were “unsubstantiated.”

The reality was more complex than what was portrayed by either side of the political battle, according to interviews with dozens of patients, parents, former employees and local health providers, as well as more than 300 pages of documents shared by Ms. Reed.

That framing suggests an equivalence between the politicians weaponizing Reed’s claims in order to ban youth access to gender-affirming care, and advocates for the people whose rights are being taken away. But what evidence does the paper provide to back up its claim that the clinic was misleading the public?

Ghorayshi reports that the university found in its internal investigation that none of its 598 patients receiving hormonal medications reported “adverse physical reactions.” She juxtaposes this with a list Reed and clinic nurse Karen Hamon privately created of 76 so-called “red flag cases”:

The list eventually included 60 adolescents with complex psychiatric diagnoses, a shifting sense of gender or complicated family situations. One patient on testosterone stopped taking schizophrenia medication without consulting a doctor. Another patient had visual and olfactory hallucinations. Another had been in an inpatient psychiatric unit for five months.

On a different tab, they tallied 16 patients who they knew had detransitioned, meaning they had changed their gender identity or stopped hormone treatments.

The suggestion, of course, is that the university is covering something up. But having a “complex psychiatric diagnos[i]s,” a “shifting sense of gender” or a “complicated family situation” in no way equates with having an adverse outcome to hormonal treatment. Nor, for that matter, does changing one’s gender identity or stopping hormone treatments.

What’s more, the Times does not report being able to confirm a single adverse physical reaction. In contrast, it does report that it found one of Reed’s claims about a child who had experienced liver damage to be misleading:

Heidi’s daughter indeed had liver damage, a rare side effect of bicalutamide. But she had been taking the drug for a year, records show, and had a complicated medical history. She was immunocompromised, and experienced liver problems only after getting Covid and taking another drug with possible liver side effects.

As for patients who detransitioned, the paper offers two examples that appear to come from Reed, and one it communicated with directly. That’s a total of three detransitions out of 598 patients receiving hormonal medications, or 0.5%.

The Times’ use of Reed’s unverified “red flag list” is perhaps its most egregious use so far of misleading numbers in its coverage on adolescent gender-affirming care. But it’s certainly not the first. The Times (11/14/22) misled its readers in its nearly 6,000-word article on puberty blockers by leading with the fact that 300,000 people between 13 and 17 identify as transgender. Only halfway through the lengthy piece do we find out that only 5,000 of them are on puberty blockers. As Assigned Media (11/14/22) noted:

There are over 25 million youth between the ages of 13 and 17. The percentage of US children ages 13–17 on puberty blockers, therefore, calculates to .02%. The percentage of trans-identifying youth on blockers, according to this article’s own numbers, would be less than 2% of trans-identifying youth. This kind of choice, to include a large number that’s not really representative of the problem, is a common one we’ve found in right-wing outlets that engage openly in anti-trans propaganda to further GOP political goals.

As in other Times stories on trans healthcare, a small number of detransitioners get a disproportionate amount of column space. The paper reports having interviewed 18 patients and their parents who said they had great experiences with the clinic. It quotes two of these patients and one parent, and spends a total of 173 words describing their experiences.

The article spends roughly twice that much ink talking about detransitioners, despite finding evidence of only three and interviewing only one. It devotes 175 words to the story of the single detransitioner the paper was able to interview, more than the amount offered to all the patients and parents with positive experiences.

None of this is to say that journalists should be doing PR for Washington University’s clinic and only telling positive stories. The St. Louis Post Dispatch (3/5/23), which covered the allegations earlier this year, spoke extensively with parents and kids, just as the Times did. It found one parent who had a negative experience, reporting she felt pressure to start her child on medication. The Post Dispatch devoted seven paragraphs to telling her story, compared to 32 paragraphs describing the experiences of the rest of the kids and parents whose accounts were largely positive and contradictory to Reed’s claims.

One of the parents quoted in the Times story, Becky Hormuth, tweeted about how little their perspectives were included:

Unfortunately, myself and the 18+ other parents mentioned and interviewed for the story last May were led to believe that our perspectives and positive experiences at the center would be highlighted, especially since [they] discredit JR in many ways. DID NOT HAPPEN!!!

Over-emphasizing stories of detransition, regret and complications by using disproportionate sourcing is common in the Times’ gender-affirming care coverage. The paper’s front-page article (9/26/22) on adolescent top surgery, also by Ghorayshi, profiled a single patient happy with their surgery, and two who regretted it.

One of those regretters, Grace Lidinsky-Smith, was also quoted in the Times Magazine‘s heavily criticized “Battle Over Gender Therapy” feature story (6/15/22; FAIR.org, 6/23/22). Along with Lidinsky-Smith—not identified in either Times story as the president of GCCAN, an advocacy group critical of gender-affirming care—that article placed a heavy emphasis on kids who considered transitioning but did not: It quoted three of them, along with a parent who refused to let their kid start hormones. By contrast, it only quoted one child who had happily transitioned, one parent who said they made the right choice, and two adults who said they had made the right choice, though one urged caution.

While the medical community’s understanding of trans and nonbinary people has evolved, most primary care physicians in the United States are still not trained on how to treat them.

Meanwhile, rates of detransition are generally estimated to be in the single digits. The current Times article (8/23/23) uses flawed interpretations of studies to suggest detransition rates higher than studies actually show, reporting that “small studies with differing definitions and methodologies have found rates ranging from 2 to 30%.” To corroborate these numbers, the Times links to a literature review whose lead author is Pablo Exposito-Campos, a researcher with ties to the Society for Evidence Based Medicine, an organization that advocates against gender-affirming care for minors.

The 30% number referenced in Exposito-Campos’ review that the Times uses comes from a study that looked at hormone prescription continuation rates in the TRICARE system for family members of military members. The authors noted in the conclusion that their numbers “likely underestimate continuation rates among transgender patients.” They also pointed out that other studies have shown as few as 16% of people who discontinue hormones do so because of a change in gender identity. (If 16% of the 30% of patients who discontinued hormone treatment did so because of a gender-identity change, that would be 0.5% of all patients.)

Notably, one of the detransitioners in the current Times article, Alex, did not regret their transition:

After three years on the hormone, she realized she was nonbinary and told the clinic she was stopping her testosterone injections. The nurse was dismissive, she recalled, and said there was no need for any follow-ups.

Alex, now 21, does not exactly regret taking testosterone, she told the Times, because it helped her sort out her identity. But “overall, there was a major lack of care and consideration for me,” she said.

Alex’s story is certainly worthy of being covered. But in attempting to frame the narrative around regret—which it couldn’t even demonstrate here—and a political debate over whether youth should even be able to access gender-affirming care, the Times missed the opportunity to discuss ignorance in the medical community of nonbinary identities, which is a genuine problem in trans healthcare.

NBC (7/13/19) reported on this problem in an extensive story profiling nonbinary people seeking gender-affirming care, and the physicians who treat them:

While the medical community’s understanding of trans and nonbinary people has evolved, most primary care physicians in the United States are still not trained on how to treat them, said Dr. Alex Keuroghlian, director of the National LGBT Health Education Center, which educates healthcare organizations on how to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people.

This is a particular issue for nonbinary people who may not fit a doctor’s or insurance company’s understanding of gender.

The Times (9/26/22) similarly questioned and manipulated numbers on detransitioners in its story on top surgery. The article referenced a study showing that out of 136 patients, only one regretted having this procedure. But it then cited another study about detransitioners:

Few researchers have looked at so-called detransitioners, people who have discontinued or reversed gender treatments. In July, a study of 28 such adults described a wide array of experiences, with some feeling intense regret and others having a more fluid gender identity.

That study, which specifically sought out detransitioners, did not mention a single person who regretted having top surgery, which was the subject of the article.

A running theme throughout the most recent Times article (8/23/23) is that the Washington University clinic, overwhelmed with new patients, did not place enough emphasis on mental healthcare. The Times gives an account from Hamon, a nurse who worked with Reed on the “red flag list”:

The ER staff, she wrote in an email, had been seeing more transgender adolescents experiencing mental health crises, “to the point where they said they at least have one TG patient per shift.”

“They aren’t sure why patients aren’t required to continue in counseling if they are continuing hormones,” Ms. Hamon added. And they were concerned that “no one is ever told no.”

The Times didn’t provide any evidence that it tried to corroborate Hamon’s claims of trans kids showing up in the ER every day, but it did paraphrase her claims as fact in the piece’s introduction: “Doctors in the emergency room downstairs raised alarms about transgender teenagers arriving every day in crisis, taking hormones but not getting therapy.” It’s a claim that cries out for factchecking, given the relatively small number of patients even treated by the clinic.

The article went on to give gross misinformation about the latest medical guidelines for trans patients, allegedly written to address these issues:

As similar mental health issues bubbled up at clinics worldwide, the international professional association for transgender medicine tried to address them by publishing specific guidelines for adolescents for the first time. The new “standards of care,” released in September, said that adolescents should question their gender for “several years” and undergo rigorous mental health evaluations before starting hormonal drugs.

The first claim is a mischaracterization. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standards of Care 7, released in 2012, had an 11-page section titled “Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Gender Dysphoria.” The new guidelines separate the treatment of children and adolescents into separate chapters for the first time, but the Times makes it sound as if WPATH had never previously issued guidelines on adolescents.

The second claim is inaccurate. The requirement that adolescents question their gender for “several years” was in the draft of the current guidelines, but was removed in the final version. Ironically, the Times links to its own article, “The Battle Over Gender Therapy,” which explains this.

The third claim is correct, that guidelines strongly recommend mental health assessments, but, again, this was also the case in the old standards of care.

The “lack of mental health support” is also contrasted with the approach being taken by several European countries:

In several European countries, health officials have limited—but not banned—the treatments for young patients, and have expanded mental healthcare while more data is collected.

European restrictions are a recurring theme in Times coverage, seemingly used to make restrictions in the US appear more reasonable. It has devoted two stories (7/28/22, 6/9/23) to England’s new restrictions on trans healthcare for adolescents. Disturbingly, neither this article nor the previous ones actually looked at the implications of prioritizing mental health treatments.

There are no studies demonstrating that psychotherapy alone is an adequate treatment for gender dysphoria. One of this approach’s most ardent proponents, the Gender Exploratory Therapy Association (GETA), concedes in its guidelines that “evidence supporting psychotherapy for GD consists only of case reports and small case series.”

The Daily Dot (7/25/23) reported that Stella O’Malley, one of GETA’s founders, admitted the approach lacks evidence:

I think we need to be careful in declaring we’re the “evidence-based side,” as most parents seek psychotherapy for their gender distressed kids and psychotherapy doesn’t have a strong evidence base.

Rather than examine why European countries are now prioritizing treatments that aren’t grounded in evidence, the Times simply expects us to believe that more “mental health treatment” is good.

The Times gave a substantial amount of deference to the claims made by Reed, a highly questionable source:

Some of Ms. Reed’s claims could not be confirmed, and at least one included factual inaccuracies. But others were corroborated, offering a rare glimpse into one of the 100 or so clinics in the United States that have been at the center of an intensifying fight over transgender rights.

This is a bizarre categorization, considering that the Times found at least two instances where Reed’s claims were contradicted by parents at the clinic. In addition to the parent who disputes Reed’s characterization about bicalutamide causing her kid’s liver damage, they found her claim that no information was being provided on the risks of treatments to be false: “Emails show that Ms. Reed herself provided parents with fliers outlining possible risks.”

The fact that the Times “could not confirm” so many of Reed’s numerous claims made in her 23-page affidavit raises questions about how hard they tried. For example, in her affidavit, Reed claims, “Most patients who have taken cross-sex hormones have experienced near-constant abdominal pain.” One would think the Times could have asked the “dozens of patients, parents, former employees and local health providers” it interviewed for this story about this supposed epidemic of stomach issues.

Reed has also made some incredibly bizarre claims, suggesting a lack of knowledge about gender-affirming treatments. In an interview with Bari Weiss and Free Press contributor Emily Yoffe (Free Press, 2/14/23), she proposed a moratorium on gender-affirming treatments, suggesting they need to be tested in animals first:

In clinical research and research that we do, there are different levels of research before you roll it out to human research studies, and there are things that you have to do first before you try it in humans, and just knowing what I know about clinical research, I think that we need a moratorium, and we need to go back to square one, and square one in drug studies is in animals.

The Times did not bother asking Reed about this claim.

It also failed to mention her affiliation with Genspect, an organization that opposes medical transition for anyone under the age of 25, and opposes bans on conversion therapy. (A 2020 study showed significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation among trans people who have been subjected to conversion therapy.)

Nor does the Times mention that Reed’s attorney, Vernadette Broyles, works with the Alliance Defending Freedom, an anti-LGBTQ hate group, and once compared LGBTQ people to cockroaches. The Times instead categorizes her as a “prominent parental rights lawyer.” It then softens her extremism by mentioning she has made derogatory comments about the trans rights movement, but omits the hateful language she has used about queer people themselves.

This is a recurring theme in the Times’ coverage, noted in the Contributors’ Letter responding to the Times’ biased coverage:

Another source, Grace Lidinksy-Smith, was identified as an individual person speaking about a personal choice to detransition, rather than the president of GCCAN, an activist organization that pushes junk science and partners with explicitly anti-trans hate groups.

The Times‘ treatment of anti-trans sources encapsulates its failure to live up to its claims of objectivity. The paper has said in response to its critics:The paper has said in response to its critics:

Our journalism strives to explore, interrogate and reflect the experiences, ideas and debates in society—to help readers understand them. Our reporting did exactly that and we’re proud of it.

It’s hard to see how readers are helped to understand these issues with such critical information omitted.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.