Oscars 2013: What the Best Picture Nominees Say About America

If an extraterrestrial landed on Earth, "Argo," "Beasts of the Southern Wild," "Django Unchained," "Lincoln," "Silver Linings Playbook" and "Zero Dark Thirty" each would be an excellent introduction to the American character. In the aggregate, they make up a composite portrait of the country. "Argo," "Beasts of the Southern Wild," "Django Unchained," "Lincoln," "Silver Linings Playbook" and "Zero Dark Thirty" all struggle with social or political issues, making up a composite portrait of the country.

Last year in this space, I made a case for the irrelevance of the Academy Awards. Given this year’s slate of nominees, I am prepared to eat some crow. I’m going to make a case for Oscar’s relevance.

From “Lincoln’s” portrait of a U.S. president pushing the 13th Amendment through a fractious Congress to “Zero Dark Thirty’s” profile of a CIA agent hunting for Osama bin Laden, six of the nine best picture nominees have unusual immediacy. Three are about the legacy of racial inequality; two about American intelligence and geopolitics; the last about a man with bipolar disorder who risks polarizing friends and family.

If an extraterrestrial landed on Earth, “Argo,” “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” “Django Unchained,” “Lincoln,” “Silver Linings Playbook” and “Zero Dark Thirty” each would be an excellent introduction to the American character. All these films struggle with social or political issues. In the aggregate, they make up a composite portrait of America.

What’s striking about these nominees, as Hendrik Hertzberg observed in The New Yorker, is how many of them engage with important events and themes in American history.

To dispense with the handicapping question upfront: My guess is that “Argo” will take best picture despite Ben Affleck’s failure to be nominated in the director category. (There tends to be a correlation between the best director and best picture winners.) What’s more attractive to Academy voters than a fact-based film in which Hollywood saves the CIA’s bacon, with a Hollywood ending to boot?

Let’s consider these six nominees alphabetically.

[Caution: For those who have yet to see these films, there are plot spoilers ahead.]

“Argo”

Affleck’s film, which was written by Chris Terrio, reflects how They see Us, how We see Them and how We pulled the wool over Their eyes. Them, of course, being non-Americans in general and Iranians in particular.

The movie begins with a prologue explaining how England and the U.S. engineered the 1953 coup in Iran that set the stage for the 1979 revolution. This provides historical context for the tensions between America and Iran that continue into the 21st century. It tells the story of six U.S. State Department workers in mortal peril during the larger crisis when Iranian revolutionaries took 52 Americans hostage in retaliation for President Carter extending political asylum to the reviled Shah of Iran.

There are many cockamamie schemes floated to spirit the State Department employees out of Iran. Cue the one from the CIA’s Tony Mendez (Affleck), who wants to pretend that the six are members of a production crew making a Hollywood sci-fi film called “Argo.” Mendez’s colleague calls it “the best bad idea.” This line invites the audience to howl in laughter at CIA bureaucrats while respecting those who had the cojones to pull off such a stunt.

Does it make sense that America-hating Iranians would be taken in by a fake Hollywood film crew? No. Yet for Americans the takeaway of the story about the phony movie that fooled the Iranians is that they may hate America, but everyone loves Hollywood.

“Beasts of the Southern Wild”

Dwight Henry, the nonprofessional actor who plays the father in this childlike parable for adults, said it best. He described the impressionistic adventure alluding all at once to surviving the flood, Hurricane Katrina and climate change as a “uniquely collaborative experience about people pulling together during disaster.” That’s what Americans do.

The film is about survival, hope and educating the next generation. From director Benh Zeitlin and screenwriter Lucy Alibar, the movie takes place in the Louisiana lowlands before and after a flood caused by the melting of the polar ice caps. It has the primal feel of a live-action version of Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are.” Narrated by Hushpuppy, a 6-year-old life force played by Quvenzhane [pronounced Kwah-van-JAHN-ay] Wallis, it is both a cautionary tale and a redemptive one. This film warns us that we have to do something about climate change, that failure to do so will hurt the weakest and poorest among us, and that with teamwork and ingenuity, we will survive.

The takeaway of “Beasts”? Reconciling a time-honored American contradiction, this tale underlines the importance of Hushpuppy remaining self-sufficient and strong while it also shows (literally and figuratively) that we are all in the same boat. That the boat in question here is a vessel with a truck body attached to a wheezing outboard motor lashed to 50-gallon drums to keep it afloat furthermore illustrates American ingenuity at its best.

“Django Unchained”

Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” is in two important ways like “Beasts of the Southern Wild.” (1) It is a parable of American inequality that (2) is directed by a white filmmaker whose entitlement to the material may seem, to some, unearned.

Can a white filmmaker make a movie about the black experience? Why not? Would a black filmmaker make a slavery revenge fantasy in which a white dentist named Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) frees a shackled slave (Jamie Foxx), arms him and teaches him a profitable trade? Doubtful. Just as it is doubtful that an African-American filmmaker would write and direct a scenario in which the most pernicious racist is the house Negro (here played by Samuel L. Jackson).

Implicitly running throughout Tarantino’s exploitative movie about human exploitation is the sense that the American crime of slavery, one gone 150 years without punishment, expiation or reparation, requires atonement. The further implication is that “Django” is that instrument of atonement.

Although “Django” is too tonally diffuse to provide one clear takeaway, the film celebrates that most American of pastimes: blood sport. Tarantino shows a spectrum of violence: freed slaves killing racists; slaves fighting one another to the death for the entertainment of their owners; attack dogs tearing apart slaves; slaves uprising and overturning the status quo. Isn’t fighting the status quo, after all, what the U.S. was built on and what Americans hold most dear?“Lincoln”

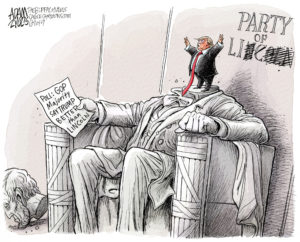

With its windy, magnificent screenplay by Tony Kushner, Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” is about politics in the concrete: what it took the 16th president to get the ornery House of Representatives to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, the one that abolished slavery.

Daniel Day-Lewis’ uncanny performance as not-always-honest Abe shows (and tells) us that the noble ideals inscribed on the creamy marble pediments of Washington monuments are fought for in the muddy trenches and smoke-filled rooms made palpable by Janusz Kaminski’s cinematography.

In 1858, Lincoln famously gave a speech that insisted, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure … half slave and half free.” Kushner employs this image of a divided House of Representatives and a divided White House to build his drama about a president who believes legislation will put the House — and his own house — back together again.

The takeaway is unmistakable: It’s a telegraph from the past to the present, from President Lincoln to President Obama and the current House of Representatives. Oration and bloviation may play to the peanut gallery, but it doesn’t get legislation passed. Mr. President, do what it takes to lead; look what Lincoln did in three months. Congress, follow or get out of the way. Put the national house together again.

“Silver Linings Playbook”

How does this story of a teacher with bipolar disorder, Pat Solitano Jr. (Bradley Cooper), a guy whose estranged wife has a restraining order against him, represent America? Glad you asked. Let’s just say director David O. Russell’s movie is likewise about a house divided, this one by a young man whose mania and depression are at odds — like America in an election year.

Consider that said teacher’s dad, Pat Sr. (Robert De Niro), a compulsive gambler with anger-management issues, is underemployed. To make ends meet, the elder Pat is a bookie. Consider that Pat Sr.’s religion and obsession is the Church of Football, denomination Philadelphia Eagles. Consider that son’s religion and obsession is his estranged wife. One believes the Eagles will win; the other that his wife will return. For both Solitanos, lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for.

And then along comes Tiffany (Jennifer Lawrence), a vibrant and volatile young widow with her own unspecified mental issues. Her openness brings both Pats out of emotional lockdown: Pat Sr. bets on his son; Pat Jr. lets go of the past.

The takeaway: As two negatives make a positive, two shaky people make each other steady. Alternatively: Who needs health insurance and a drug plan when love is a natural mood stabilizer?

“Zero Dark Thirty”

Even its detractors can agree that Kathryn Bigelow’s political procedural about the CIA hunt for Osama bin Laden has fueled civic debate on the immorality and inhumanity of torture. Still, I disagree with Jane Mayer, one of the film’s most knowledgeable and eloquent critics, that the movie constitutes “false advertising for waterboarding.” That isn’t my takeaway.

The film, written by Mark Boal, opens with audio of the al-Qaida attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 and concludes with the Navy SEALs’ attack on bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound in Pakistan in 2011, including bin Laden’s assassination. Early on, it contains by my count three excruciating scenes of CIA operatives using what are euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Some viewers claim the movie shows that waterboarding directly led the CIA to the whereabouts of the elusive bin Laden. The film I saw, in which seven years elapse between the dehumanizing scene of waterboarding and bin Laden’s assassination, makes at best an indirect link between torture and Abbottabad.

The movie shows its central figure, CIA intelligence analyst Maya (Jessica Chastain), being as single-minded about finding the architect of the attack on the twin towers as Lincoln was about getting the 13th Amendment passed. As the film tells it, Maya has no life outside of work. She prevails through two presidential administrations and CIA reshufflings holding her superiors’ feet to the fire.

In the film’s penultimate sequence, SEALs’ mission accomplished, Maya identifies bin Laden’s body. In the final shots, tears streaking her ashen cheeks, she boards a military transport. What is she thinking? It reminded me of the allusive final scene of “The Graduate” in which each moviegoer projects his or her feelings onto the characters. For me, the takeaway of “Zero Dark Thirty” is “Revenge is bitter.”

In the Oscar-nominated best pictures of 2012 we are less likely to encounter the pursuit of happiness than that of survival and professionalism. The thread running through these films, one that ties Tony Mendez to Hushpuppy to Django to Lincoln to Tiffany to Maya, is that America may not be a land of liberty, but it’s definitely a land of tenacity, and a land where the tenacious create their own community.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.