This Pakistani Festival Makes Education a Fun Activity

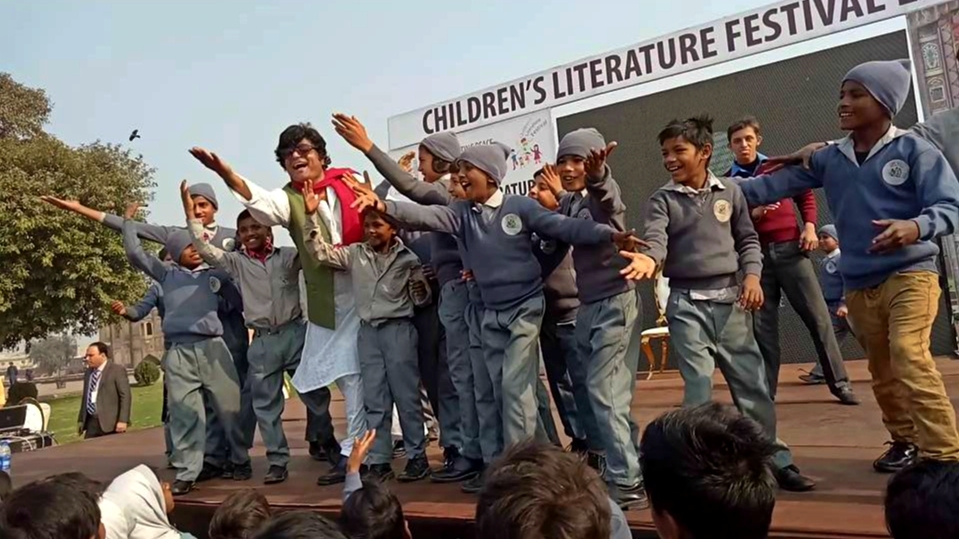

In a country where public school systems are failing, a growing nonprofit organization shows students and teachers how to revitalize learning. Atif Badar leads children in an interactive theater workshop at the Children's Literature Festival in Lahore, Pakistan, in January. (Zubeida Mustafa)

Atif Badar leads children in an interactive theater workshop at the Children's Literature Festival in Lahore, Pakistan, in January. (Zubeida Mustafa)

In January 2018, Lahore, the seat of government of Pakistan’s largest province, Punjab, played host to the Children’s Literature Festival (CFL), a unique experiment in making education a fun activity. Thousands of children gathered on the scenic lawns of the historic Lahore Fort to hear stories, listen to music and songs, and watch plays and dances.

But this was not an entertainment event alone. It was more like a gigantic, unconventional school, and in many cases the children were their own teachers.

January’s festival was not entirely new for the people of Lahore. In 2011 a similar event—albeit one a bit more serious—was held on the Punjab Public Library grounds. In 2014 Lahore again played host to the CLF.

The CLF has come a long way over the course of its six-year journey. The session in January was the 45th held in Pakistan since 2011. So far, the CLF has reached a million children. It is now a registered company with six directors and a secretariat at the Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (“Center for Education and Consciousness,” or ITA), the parent organization under which CLF was originally conceived. ITA provides secretarial and technical support to CLF so that the latter remains a lean organization with minimal overheads and maximum outreach. The CLF has gone all over Pakistan, from big cities to small towns. Over the years it has evolved and has crept into neighboring cities in India and Nepal as well.

How did it all begin? The United Nations recognizes education as a child’s right. Yet UNESCO estimates that 263 million children are out of school worldwide. Since education is linked closely to development and progress, the U.N. attached much importance to education when creating its Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015) and Sustainable Development Goals (2015-2030). The first blueprint sought universal primary education by 2015. The second has set the goal of quality education up to secondary level for all children by 2030. Pakistan never achieved the first. For that country, the second also appears to be beyond reach.

At present, almost 23 million children are believed to be out of school in Pakistan. It is not just lack of access that is a problem—the poor quality of education nullifies whatever small advantage is achieved in terms of enrollment. Both issues need to be addressed if the universalization of education is to be meaningful.

Of course, not all Pakistani children enrolled in school learn the basic literacy and numeracy skills needed to promote lifelong learning. Some of the statistics released from time to time are dismal in the extreme.

Only 77 percent of primary-school age children are enrolled, of which only 49 percent reach the lower secondary classes. As a result, the literacy rate for those above 10 years of age is only 60 percent. The situation for girls is even worse.

The reason for the low enrollment is the government’s failure to open educational institutions: In 2016, there were only 121,674 primary schools in the public sector for children ages 5 to 9. The number of schools has declined due to the merger of inefficient schools and the closing of nonfunctional institutions. Meanwhile, the number of children of school age has increased. We shall know more about the effects of this when the results of the 2017 census come in.

Another reason for the government’s failure to win over parents to enroll their children in state schools, which are at low capacity, is the appalling quality of education being imparted there. The private sector has been filling the vacuum, but a large segment of the population cannot afford the fees charged by private schools, even at so-called “low-fee” private schools. The poor performance of government schools hardly provides the incentive the underprivileged need to provide their children an education. Parents are not fools and understand they are being duped in the name of education. The only answer to this problem is to make schools more effective so they actually teach children necessary skills.

A visit to a typical public sector school can be a depressing experience. The physical environment is generally appalling, and the quality of education is poor. This is evident from the low learning outcomes of the children studying there. ITA is also well known for its citizen-led nationwide learning accountability survey called the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER). ASER was conceived as a social movement to conduct annual surveys to assess children’s academic performance. It testifies that in the households its surveyors visited in 2016, only 52 percent of children in Grade 5 could read a story at Grade 2 level in a local language.

All of these worrying trends sparked the creation of the CLF in 2011. Dr. Baela Raza Jamil, an academic, public policy specialist associated with many education-related bodies and a member of the Technical Advisory Group of the U.N. Secretary General’s Global Initiative on Education, began to think up new methods that would inspire children to learn in more interesting ways rather than reading dull texts and memorizing passages without acquiring any knowledge. She wanted to make the learning process a “fun thing” and make books more like toys, which children could enjoy.

The first few children’s festivals concentrated on storytelling and talks for children. There was a lot of emphasis on books of all kinds, art, music and competitions. In the early years, the idea was to draw children out of their classrooms and get them to enjoy reading by participating in activities that are normally not seen as means of learning.

Dr. Jamil sees the Children’s Literature Festival as a social movement, one that has introduced liberated content and an enriching, multisensory experience into learning as an alternative narrative to Pakistan’s rigid form of education. She calls it “a learning, feeling and healing experience, which is an antidote to terrorism, cynicism and aggression. Children come here happy and leave happier still, full of hope and optimism.”

The CLF is pushing for change, as its anthem, penned by Pakistan’s distinguished poet Zehra Nigah, states: “Humain kitab chahiyay/Jo zindagi badal day wo nisab chahiyay” (“We want books. We want a syllabus that would change our lives”).

The demand for the CLF now comes from the grass roots; it is no longer an event imposed by a small group from above. The involvement of schools is growing, as more and more schools are stepping in to hold their own literature festivals, bringing together groups of neighboring institutions with guidance from the CLF team.

As I strolled the grounds of the Lahore Fort in January, absorbing the joyous laughter and singing of the children, I could sense their involvement in the day’s activities. I saw children carefully making books under the guidance of the Oxford University Press (Pakistan) team. In another session, children were listening with great concentration to author Musharraf Ali Farooqi read a story, joining him every few minutes in the “chorus line” that every story for young children has.

There was also Lalahrukh Malik, the science communicator, who had set up a simple open-air lab and was guiding young ones in carrying out simple experiments. They were clearly enjoying themselves. Further on was Sheherzade Alam, Pakistan’s famous ceramicist, with her clay and potters. For the children it was a heaven-sent opportunity to play with clay and mold it into little shapes. Atif Badar, the theater teacher, was present with his colorful puppets, encouraging children to sing and dance and perform skits and plays, many of them of their own creation.

An idea that is gaining popularity is to get children to write a script and dialogues based on a graphic story and present it as a play. Oxford University Press (OUP), the prestigious publishing house, has commissioned a series of books called “Tasveeri Kahani Silsila” (“Graphic Stories Series”), based on the lives of famous personalities of Pakistan and authored by Amina Azfar and Rumana Husain. Many of the individuals, such as the iconic poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, have been picturized more than once. At the festival in Lahore, a group of children from the Sanjan Nagar School decided to present a play based on my own biography, which has been honored by the OUP.

It was evident that the CLF had become more participatory. Children are now involved as contributors, not silent spectators. They are no longer expected to sit and watch and listen. They are the actors who learn as they perform.

As designed for children 4 to 18 years of age, the CLF is also meant to be an equalizer for the multiplicity of school systems—another curse of the education system in Pakistan that leads to great inequity in society. The CLF does away with discrimination and celebrates diversity. The pity is that few elite schools send their students to the CLF. Hopefully this will change, given Dr. Jamil’s commitment to social justice.

As the reach of the CLF grows, one hopes it will enter the classrooms as well, forcing the education managers to emulate the CLF’s underlying pedagogic theme: Learning can be made fun.

But this doesn’t mean that the basics of education (the “three Rs”) can be dispensed with. To teach reading, writing and mathematics, teachers are needed—and yet, teachers are the Achilles’ heel of education in Pakistan.

The CLF has tried to address this issue, and three Teachers’ Literature Festivals have been held to motivate teachers. This is the most essential need of the day. Children love the festivals, which are not an ongoing event; they then return to their teachers, who alone have the power to make the classroom a “fun place.”

And that is what Pakistan needs most.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.