Pardoner-in-Chief

A Trump self-pardon would be unprecedented, but would it be unconstitutional? Former President Donald Trump speaks during the Faith & Freedom Coalition Policy Conference in Washington, Saturday, June 24, 2023. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Former President Donald Trump speaks during the Faith & Freedom Coalition Policy Conference in Washington, Saturday, June 24, 2023. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

June 4, 2018 is not considered a landmark date in the annals of American legal history, but perhaps it should be. On that day, Donald J. Trump, the 45th president of the United States, took to Twitter and declared, “I have the absolute right to PARDON myself…”

Trump’s tweet was part desperation and part defiance. It was dispatched in the midst of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into alleged Russian meddling in the 2016 election. At the time, Trump feared Mueller’s probe could lead to his prosecution for conspiracy and obstruction of justice once he left office and was no longer shielded by the Justice Department’s policy against indicting a sitting president. A self-pardon would serve as his get-out-of-jail card. It would also be entirely without precedent in American history.

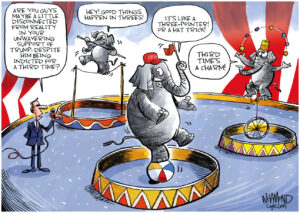

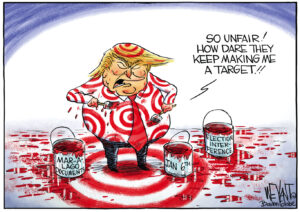

Trump survived the Mueller probe unscathed and uncharged. But now that he is running for reelection following an indictment for absconding to Mar-a-Lago with a trove of top-secret documents (and may yet be charged for his part in the Jan. 6th insurrection) the self-pardon issue has reemerged with renewed urgency.

If Trump is reelected, he could well become the first and only American president to immunize himself from criminal prosecution. And as incredible as it may seem, he might be able to do so constitutionally.

A self-pardon would serve as his get-out-of-jail card. It would also be entirely without precedent in American history.

The pardon power is inscribed in Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, which bestows upon the president the prerogative “to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

The impeachment limitation explains why Trump did not pardon himself in connection with his two impeachments, the first of which began with a House vote on Dec. 18, 2019, and the second with a House vote on Jan. 13, 2021, just days before the inauguration of Joe Biden. In addition to cases of impeachment, the power is also limited in two other important respects: Presidents cannot pardon individuals accused of committing state crimes. Nor can they grant pardons for future federal crimes that have not yet taken place.

Apart from these restrictions, however, the pardon power is vast. As the Supreme Court observed in Ex parte Garland, an 1866 ruling involving a pardon granted by President Andrew Johnson to a former member of the Confederacy:

The power thus conferred is unlimited, with the [impeachment] exception stated. It extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken, or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment. This power of the President is not subject to legislative control. Congress can neither limit the effect of his pardon, nor exclude from its exercise any class of offenders. The benign prerogative of mercy reposed in him cannot be fettered by any legislative restrictions.

As the Garland decision indicates, pardons can be exercised broadly and preemptively. Gerald Ford famously pardoned Richard Nixon preemptively “for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed.”

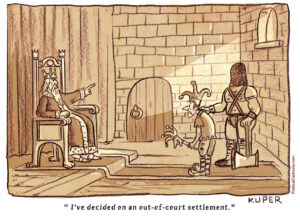

Like Trump, Nixon considered a self-pardon before Ford came to his rescue. As Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein chronicled in their 1976 book “The Final Days,” Nixon discussed the possibility of a self-pardon with his aides and attorneys for his role in the Watergate break-in and cover-up, but was dissuaded from acting. A legal memorandum written by the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) three days before Nixon announced his resignation on live TV on Aug. 8, 1974, concluded that despite the pardon power’s expansive reach, “Under the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case, it would seem that the question [of a self-pardon] should be answered in the negative.”

The OLC is a unit of the Justice Department that offers legal advice to the president and executive branch agencies. Its opinions are highly valued, but they are not the law.

That’s the key to predicting what could happen if Trump is given a second chance at the presidency. Trump is far more of a threat to constitutional norms and the rule of law than Nixon ever was. If returned to the White House, he would likely dismiss the OLC memo as dated and irrelevant. Indeed, in a confidential 20-page letter sent to Mueller in January 2018 and later obtained by The New York Times, Trump attorneys Jay Sekulow and John Dowd suggested he could pardon all those targeted by the probe, including himself.

As the Garland decision indicates, pardons can be exercised broadly and preemptively.

Trump subsequently pardoned several of Mueller’s targets, including Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort and his first national security adviser Michael Flynn. But he stopped short of pardoning himself, perhaps in the mistaken belief that after evading Mueller, he would never actually be indicted.

That caution is now gone. A reelected and indicted Trump will stop at nothing to insulate himself from legal accountability and possible imprisonment. A rational actor might be content with firing Special Counsel Jack Smith and appointing a new attorney general to exact revenge on the Biden administration, but Trump has never been a rational actor.

Still, Trump could expect legal challenges to a self-pardon. Constitutional law experts are divided on whether any challenges could succeed.

“The arguments about whether a president can pardon himself are not only unsettled in the sense that they haven’t come up before, but they’re also unsettled in the sense that reasonable lawyers could look at the materials [the Constitution, and the history of prior pardons] and say either result is legally defensible,” Harvard Law School professor Mark Tushnet told CBS News earlier this month.

“One perspective is that the pardon power is quite broad, and the Constitution does not explicitly forbid a self-pardon,” said Jeffrey Crouch, an expert on executive clemency, in a recent interview with Yahoo News. “The other perspective is that a self-pardon would, among other things, inappropriately allow the president to decide his fate in his own case. At some point, the U.S. Supreme Court would likely have to decide on the constitutionality of a self-pardon.”

A ruling by the Supreme Court, stacked with three Trump appointees and two angry old reactionaries, is nothing the liberal or progressive left should welcome. We don’t want to give Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett the opportunity to equip Trump with prerogatives befitting a Medieval monarch or the dictator of a developing nation.

A far better defense against a future self-pardon is to keep Trump from being reelected in the first place. One term was almost enough to destroy what remains of American democracy. A second would be crippling.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.