Patty Hearst, Double Agents and the Symbionese Liberation Army

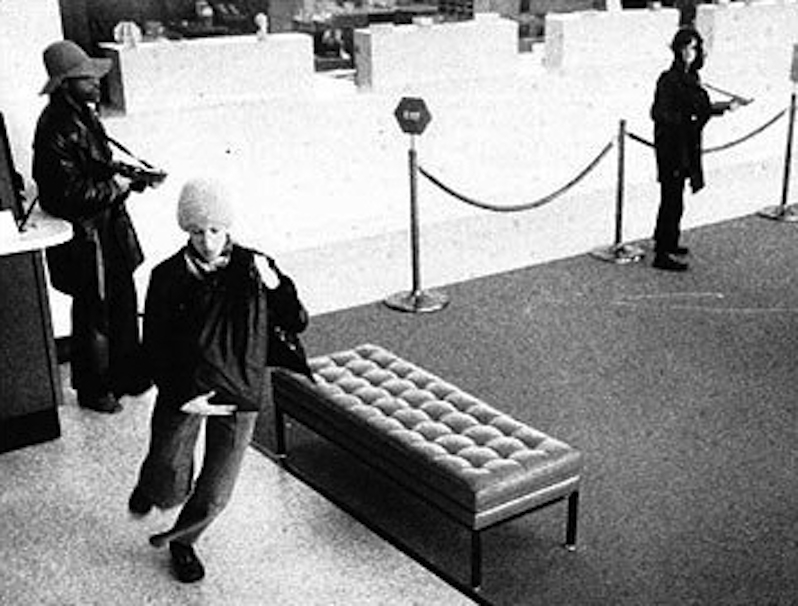

Jeffrey Toobin’s new book about the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst by the SLA in 1974 fails to treat the revolutionary group in sufficient detail. SLA members Donald DeFreeze, Patricia Soltysik (in foreground) and Patricia Hearst during the robbery of Hibernia Bank in San Francisco. (Wikimedia Commons)

SLA members Donald DeFreeze, Patricia Soltysik (in foreground) and Patricia Hearst during the robbery of Hibernia Bank in San Francisco. (Wikimedia Commons)

By Paul Krassner

Jeffrey Toobin’s new book, “American Heiress,” presents a mean-spirited approach to the kidnapping of Patty Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, but he’s clueless about the significance of the SLA, for which she was forced to rob a bank. I covered her trial for the weekly underground paper, the Berkley Barb.

At the end of a tape by Hearst, Donald “Cinque” DeFreeze, the SLA’s black leader of a white group, came on with a triple death threat, especially to Colston Westbrook, whom he accused of being “a government agent now working for military intelligence while giving assistance to the FBI.” This communiqué was sent to San Francisco radio station KSAN. News director David McQueen checked with a Justice Department source, who confirmed Westbrook’s employment by the CIA.

Conspiracy researcher Mae Brussell traced Westbrook’s activities from 1962, when he was a CIA advisor to the South Korean CIA, through 1969, when he provided logistical support in Vietnam for the CIA’s Phoenix program. His job was the indoctrination of assassination and terrorist cadres. After seven years in Asia, he was brought home in 1970 and assigned to run the Black Cultural Association at Vacaville Prison, where he became the control officer for DeFreeze, who had worked as a police informer from 1967 to 1969 for the LAPD’s Public Disorder Intelligence Unit.

If DeFreeze was a double agent, then the SLA was a Frankenstein monster, turning against its creator by becoming in reality what had been orchestrated only as a media image. When he snitched on his keepers, he signed the death warrant of the SLA. They were burned alive in a Los Angeles safe house during a shootout with police. When Cinque’s charred remains were sent to his family in Cleveland, they couldn’t help but notice that he had been decapitated. It was as if the CIA had said, literally, “Bring me the head of Donald DeFreeze!”

Consider the revelations of Wayne Lewis in August 1975. He claimed to have been an undercover agent for the FBI, a fact verified by FBI director Clarence Kelley. Surfacing at a press conference in Los Angeles, Lewis spewed forth a veritable conveyor belt of conspiracy charges: that DeFreeze was an FBI informer; that he was killed not by the SWAT team but by an FBI agent because he had become “uncontrollable”; that the FBI then wanted Lewis to infiltrate the SLA; that the FBI had undercover agents in other underground guerrilla groups; that the FBI knew where Patty Hearst was but let her remain free so it could build up its files of potential subversives.

In February 1976, while Hearst’s trial was still in process, a similar charge was made when a Berkeley underground group, Tribal Thumb, prepared this statement:

Donald DeFreeze escaped from the California prison system with help from the FBI and California prison officials. His mission was to establish an armed revolutionary organization, controlled by the FBI, specifically to either make contact with or undermine the surfacing and development of the August Seventh Guerrilla Movement…DeFreeze was let loose and given a safe plan to surface as an armed guerrilla unit. That plan was to kidnap Patty Hearst.

One warm afternoon I was surprised to receive a letter by registered mail on Department of Justice stationery.

Dear Mr. Krassner:

Subsequent to the search of a residence in connection with the arrest of six members of the Emiliano Zapata Unit, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, San Francisco, has been attempting to contact you to advise you of the following information:

During the above indicated arrest of six individuals of the Emiliano Zapata Unit, an untitled list of names and addresses of individuals was seized. A corroborative source described the above list as an Emiliano Zapata Unit “hit list,” but stated that no action will be taken, since all of those who could carry it out are in custody.

Further, if any of the apprehended individuals should make bail, they would only act upon the “hit list” at the instructions of their leader, who is not and will not be in a position to give such instructions.

The above information is furnished for your personal use and it is requested it be kept confidential. At your discretion, you may desire to contact the local police department responsible for the area of your residence.

Very truly yours, Charles W. Bates Special Agent in Charge

However, a source informed me that the Zapata Unit was a front for the FBI. Was the right wing of the FBI warning me about the left wing of the FBI? Questions about the authenticity of the Zapata Unit had been raised by its first public statement in August 1975, which included the unprecedented threat of violence against the left. After publishing in the Barb the FBI’s letter to me, I received a letter from a member of the Zapata Unit in prison:

I was involved in the aboveground support group of the Zapata Unit. Greg Adornetto led myself and several others to believe we were joining a cell of the Weather Underground, which had a new surge of life when it published Prairie Fire. I knew nothing about a hit list or your being on one, and can’t imagine why you would have been. When we were arrested, FBI agent-provocateur Adornetto immediately turned against the rest of us and provided evidence to the government.

In 1969, Charles Bates was a Special Agent at the Chicago office of the FBI when police killed Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark while they were sleeping. Ex-FBI informer Maria Fischer told the Chicago Daily News that the then-chief of the FBI’s Chicago office, Marlon Johnson, personally asked her to slip a drug to Hampton; she had infiltrated the Black Panther Party at the FBI’s request a month before. The drug was a tasteless, colorless liquid that would put him to sleep. She refused. Hampton was killed a week later. An autopsy showed “a near fatal dose” of secobarbital in his system.

In 1971, Bates was transferred to Washington, D.C. According to Watergate burglar James McCord’s book, “A Piece of Tape,” on June 21, 1972 (four days after the break-in), White House attorney John Dean checked with acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray as to who was in charge of handling the Watergate investigation. The answer: Charles Bates—the same FBI official who in 1974 would be in charge of handling the SLA investigation and the search for Patty Hearst. When she was arrested, Bates became instantly ubiquitous on radio and TV, boasting of her capture.

And, in the middle of her trial—on a Saturday afternoon, when reporters and technicians were hoping to be off duty—the FBI called a press conference. At five o’clock that morning, they had raided the New Dawn collective—supposedly the above-ground support group of the Berkeley underground Emiliano Zapata Unit—and accompanying a press release about the evidence seized were photographs still wet with developing fluid. Charles Bates held the photos up in the air.

“Mr. Bates,” a photographer requested, “real close to your head, please.”

Bates proceeded to pose with the photos. But was there a search warrant? No, though they had a “consent to search” signed by the owner of the house, Judy Sevenson, who admitted to being a paid FBI informant.

Jacques Rogiers—the above-ground courier for the underground New World Liberation Front (NWLF) who delivered their communiqués—told me that the reason I was on the hit list was because I had written about Donald DeFreeze being a police informant.

“But that was true,” I said. “It’s a matter of record. Doesn’t that make any difference?”

Apparently, documentation didn’t make any difference.

“If the NWLF asked me to kill you,” Rogiers admitted, “I would.”

“Jacques,” I replied, “I think this puts a slight damper on our relationship.”

My 11-year-old daughter and I moved to another house.

Graffiti on our house included “SLA LIVES,” which was then obscured in the enigmatic made-over “COLE SLAW LIVES,” a slogan that baffled tourists and convinced one that a political activist named Cole Slaw was dead because it said that he was alive.

Paul Krassner’s latest book, “Patty Hearst and the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials,” is published by PM Press.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.