Portraits of His People: A Tribute to Willie Middlebrook

Willie Middlebrook's untimely death at the age of 54 on May 4 brought an end to the work of one of the finest and most socially conscious artists of our times.

A major highlight of my research career has been to document and celebrate the vibrant tradition of African-American visual art in Southern California and throughout the United States. For well over 25 years, I have had the privilege and pleasure of interviewing African-American artists working in a vast array of visual media, including photography. Among the most engaging of these artists was Willie Middlebrook. His untimely death at the age of 54 on May 4 brought an end to the work of one of the finest and most socially conscious artists of our times.

Widely exhibited since the early 1970s, he created a prolific body of work throughout his artistic career. His early documentary photographs of street life, especially about the homeless in downtown Los Angeles and African-Americans in Watts, generated widespread attention and respect. Those works from the 1970s and ’80s reflected his powerful ability to interact closely and sensitively with his subjects, ensuring that the final images reflected a compelling vision of human beings that society had rejected as marginal and superfluous. He also documented the grinding economic deprivation of these areas, exposing the deplorable conditions of urban life for millions of his fellow people of African descent. His views of liquor stores, police occupations and similar features of inner city Los Angeles highlighted the underlying conditions that have given rise to two major urban rebellions since 1965. In the process, Middlebrook established himself as the legitimate heir of such iconic black photographers as James Van Der Zee, Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks.

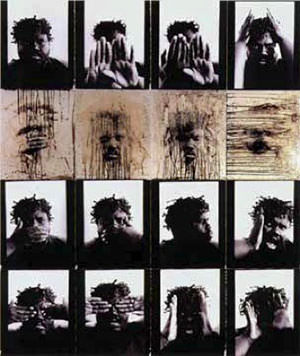

If he had remained a documentary photographer exclusively, his artistic reputation would have been secure. In mid-career, however, he began employing photographic elements and techniques in imaginative ways to produce the style that he called photographic paintings. He sprayed and brushed on developing fluid to produce a stunning effect, often working on much larger scale works than typically found in traditional documentary photographs. Adding toner and bleach to determine and control the emotion of specific images, he produced a large body of work that he cumulatively called “Portraits of My People.”

The works in this series were the signature efforts of his distinguished career. They were dedicated to the black community and reflected his thoughtful artistic credo and philosophy. Middlebrook articulated his vision clearly in his personal artistic statement:

“Art is about communication. … I need to tell, to show what I see, what I feel. I am intrigued and motivated by life experience, the human condition. … My subjects — family and friends — and I have an understanding focused towards a single goal: to speak about our people, our communities. My drive, my direction, my strong social and aesthetic convictions in everything I do stems from my parents, who endowed me with strong feelings about the ideals and the integrity of being black.”

This perspective has pervaded African-American art since the Harlem Renaissance. For Middlebrook, the portraits of his people fundamentally repudiated the dominant racial imagery of American popular culture.

By showcasing African-Americans as beautiful, accomplished and intelligent, he implicitly criticized a society that has rarely portrayed them positively and respectfully. His deeply sensitive images of black women in this series, moreover, were pointed contrasts to depictions of them as prostitutes, sexual degenerates, welfare cheats and other unsavory roles. Throughout his life, he used his art effectively as a visual antidote to the destructive and distorted portrayals of black people over the centuries.

That vision was at bottom fundamentally political — another key feature of African-American visual art for more than a hundred years. Middlebrook’s body of work joins those of such luminaries as Meta Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, Charles White, Romare Bearden, John Biggers, Elizabeth Catlett, John Scott, Samella Lewis, Faith Ringgold, David Hammons, John Outterbridge and hundreds of others in using art to provide critical commentary about race and racism in American history and society. Many of my personal conversations with him over the years confirmed his strong political consciousness, especially about his driving need to create a stronger, more realistic vision of his own people. He regularly reiterated how he wanted his artworks to validate the essential decency and honesty of the overwhelming majority of the African-American population.

Middlebrook also used his works to offer incisive observations about specific political events. In one example from “Portraits of My People,” he used his art to comment on the savage 1991 beating of Rodney King and the subsequent acquittal of the four Los Angeles Police Department officers responsible for that grotesque injustice. More recently, he incorporated imagery of the three murdered civil rights martyrs in Mississippi in 1964, boldly included the word “nigger” to defang the insidious power of that notorious example of racial invective, and addressed the issue of slavery and the middle passage in his artworks. Together, these trenchant efforts elevated him to the top rank of socially conscious artists of the contemporary era.

Beyond his remarkable artistic content, Middlebrook also took photography to new levels of visual creativity and excellence. Like his African-American contemporaries Adrian Piper, Carrie Mae Weems, Lyle Ashton Harris, Lorna Simpson, Pat Ward Williams, Renee Cox and several others, he used a photographic foundation to make huge formal advances in contemporary visual art, establishing himself as a profound innovator in the field. His recent works especially revealed the combination of technical excellence and incisive content that properly propelled him to the forefront of the African-American visual tradition in the early 21st century.

In addition to his portraits, he also mentored young artists through his work as an arts administrator and teacher at Compton College and Cal State L.A. He was always committed to the needs of his younger peers, following in the long tradition of African-American artists seeking to extend the tradition of visual creativity.

Near the end of his life, Middlebrook’s photographs were included in two of the recent exhibitions organized under the sponsorship of the Getty Pacific Standard Time initiative. His works at Cal State Northridge and the California African American Museum last year and this were seen by thousands of appreciative viewers. Moreover, his permanent legacy includes 24 mosaic artworks at the Expo/Crenshaw Station on the Expo Line, the Avalon Station on the Metro Green Line and the L.A. County Florence-Firestone Service Center.

Several years ago, in one of my early interviews with Middlebrook, he remarked that he had “12 million ideas” for future artworks and projects. He died well before he could fulfill that ambitious objective, but he was well under way, leaving us a remarkable body of work that reflected his passionate drive to communicate, record and validate the lives of his fellow African-Americans. Those portraits of his people remind us all that the struggle for racial justice and dignity continues in the early years of this new century. In his all too short lifetime, Willie Middlebrook helped move us in that direction.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.