Trump’s Curious Pardon of Former Heavyweight Champ Jack Johnson

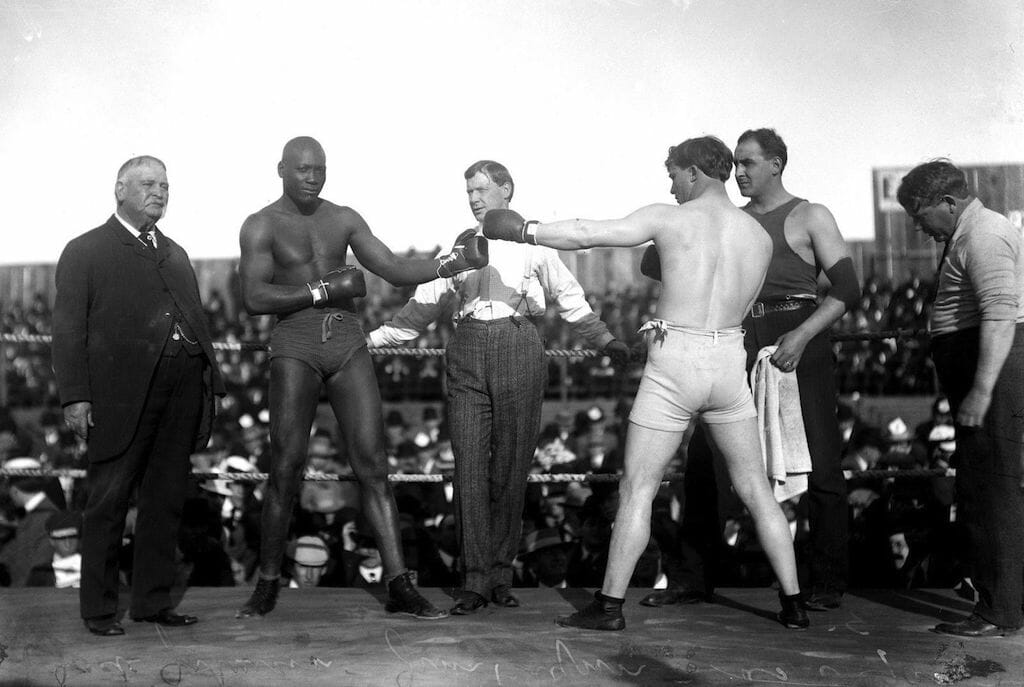

A more perfect match between president and African-American icon could not be imagined. Jack Johnson, left, and Jim Flynn in a 1912 heavyweight championship bout in Las Vegas, New Mexico. (Wikimedia)

Jack Johnson, left, and Jim Flynn in a 1912 heavyweight championship bout in Las Vegas, New Mexico. (Wikimedia)

As you no doubt heard—or maybe you didn’t in the latest flurry of scandals and outrages—President Trump has posthumously pardoned former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson. A more perfect match between president and African-American icon could not be imagined.

Born in 1878—or sometime around then (there are no surviving records)—Johnson grew up in the port city of Galveston, Texas, a town relatively, for the time and place, relaxed on racial matters. He grew up playing with white kids, unaware of the restrictions he would face in the outside world as he grew older. When, in later life, he was confronted by those boundaries, he simply ignored them.

John Arthur Johnson held the crown from 1908-1915, the first black man to claim it. At 6 feet tall and around 200 pounds, he was big for his day, a solid puncher with either hand, and an outstanding defensive fighter. How good he was is still a subject of debate among boxing historians, as Johnson never faced a top-flight heavyweight during his prime. For what it’s worth, though, Nat Fleischer—who founded Ring magazine, “The Bible of Boxing,” in 1922—thought that Johnson was the best ever.

Jack Johnson won the title in 1908 in Sydney, Australia, from Tommy Burns, who, at about 5 feet 7 inches and 190 pounds, was perhaps the most insignificant man ever to hold the division crown. Johnson toyed with his much smaller foe, cutting up his face, slapping away his punches and taunting him: “Tawmee, Tawmee, is that hardest you can hit?”

The fight was so lopsided that Jack London, watching from ringside, called it “a hopeless slaughter.” In his dispatch, London sent out a call for what would quickly come to be called “A Great White Hope,” former champion Jim Jefferies. “Jefferies,” London said, “must now emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you. The White Man must be rescued.”

The Johnson-Jefferies fight, held in Reno, Nev., in 1910, was the first bout to be billed as “The Fight of the Century.” It might have been that if they’d fought a few years earlier. Jefferies, who had won the title in 1899 by knocking out Ruby Bob Fitzsimons, was, at his peak, 6 foot 2 inches and 220 pounds, and Fleischer thought young Jefferies to be nearly the equal of Johnson. But by 1910, he was 35 and had been inactive for years. Living on his California farm, he had ballooned to around 300 pounds and had to lose 70 of them in just a few months. His performance against Johnson was pathetic. In the 15th round, Johnson, who had mostly sparred with a helpless Jefferies, dropped the former champ three times, and Jefferies’ handlers rushed into the ring to save their man the ignominy of being knocked out.

Black euphoria over Johnson’s victory was met with white fury as black men all over the country were attacked, beaten and even lynched. One report a few days after the fight claimed 20 murdered. If Johnson was dismayed by the violence, he gave no sign.

Now rich enough to afford automobiles, he raced them down public streets, and when stopped by white policemen, whipped out some bills from his wallet and told them to “Keep the change.” According to a story that has never been verified but certainly could be true, Henry Ford gave Johnson a new car every year, assuming that when he was pulled over for speeding, a photo of a grinning Jack beside his shiny new Ford would appear in newspapers across the country. The old saw “You can’t buy publicity like that” comes to mind.

Johnson mocked and taunted his white opponents and derided his black rivals, including the great Sam Langford, whom, after he became champion, he refused to meet in the ring. (Johnson endured a tough decision over Langford when they were both challengers for the title, but when he became champ barred Langford and all other black contenders.) The first champion of the gloved era, John L. Sullivan, had refused to fight a black man, but Johnson drew his own color barrier. That color barrier did not apply out of the ring: Johnson publicly romanced and even married a white woman. The singer Ethel Waters, who apparently resisted Johnson’s ardent advances, told him, “It’s universally known, Jack, that you have the white fever.”

Johnson expressed no solidarity with other black Americans and even took pains to distance himself from their spokesmen. As Paul Beston writes in his superb history of the American heavyweight division, “The Boxing Kings,” “[W.E.B.] DuBois and [Booker T.] Washington agreed that a black man in the public eye had broader responsibilities to the race. Johnson didn’t think so. ‘I have found no better way of avoiding racial prejudice,’ he wrote, ‘than to act in my relations with people of other races as if prejudice did not exist.’ Individualism was his creed.”

Simply put, Johnson lived a philosophy as free from identity politics as a Fox News commentator.

In 2004 biography, “Unforgiveable Blackness,” (the basis for the Ken Burns documentary), Geoffrey Ward demolished the myth of Jack Johnson as a role model for black activists. “He never seems to have been interested in collective action of any kind. How could he be when he saw himself always as a unique individual apart from everyone else?”

Johnson lost the title to the ponderous Jess Willard (6 feet 6 inches tall, 250 pounds) in Havana in a 26-round knockout in 1915. Johnson would later claim that he could have gotten up but, lying on his back, he lifted his hand to shield his eyes from the sun (as shown in the film). There’s no clear evidence that this is what happened, nor is it clear that the fight was fixed, as rumored, nor is it clear what the fight told us about Johnson (who was 37 and overweight) or Willard (a mediocre fighter at best, who was butchered in four rounds by Jack Dempsey just three years later).

The law didn’t get Johnson for fixing fights, though lots of fighters, managers and promoters back then were known to be involved in fixes, and, in fact, the taint has never left the fight game. The law got Johnson on the Mann Act of 1910, also known as the White-Slave Traffic Act, which prohibited the transporting of women across state lines for what was deemed “immoral purposes,” or, stated another way, prostitution. In the wake of public outrage against the black man who insulted white opponents and slept with white women, the feds almost immediately went to work to build a case against Johnson as soon as he won the title from Burns in 1910; it took them three years.

In September 1912, Johnson’s white mistress, Etta Duryea, the ex-wife of a Wall Street broker, took her own life. Duryea had reportedly been drinking through bouts of depression spurred by Johnson’s infidelities and, she confessed to friends, physical abuse. After a brief but intense period of mourning, Johnson began keeping company with Lucy Cameron, an 18-year-old white girl who had been arrested the year before for practicing a trade even older than Jack’s. Cameron’s mother charged Johnson with kidnapping and pimping her daughter; the charges were, at best, contrived, and after Johnson was arrested in Chicago, he was released on bail. Johnson married Lucy, and the case fell apart.

The feds wouldn’t quit. They found another prostitute—white, of course—Belle Schreiber, who testified that Johnson had indeed taken her across state lines for professional purposes. Again, the government’s case was shaky, but that was of no concern to the all-white jury and Illinois Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who sentenced him to federal prison for a year. Landis’s service to the white race would not be forgotten: Years later, he was named the first commissioner of big league baseball and banned several members of the championship 1919 White Sox from the game for throwing the World Series.

Jack and Belle skipped the country for Europe, and for two years, he made money fighting exhibitions with second-rate challengers. Johnson would later claim that he agreed to throw his fight against Willard for a big payday, at least $30,000 (more than $700,000 today) and a light sentence.

This was never proven. Still, Johnson’s claims were plausible. He served a year in Leavenworth, where he taught prisoners to box, and, according to one news story, was granted special favors from prison guards for autographing boxing gloves and other items. In 1927 he published a memoir, “In The Ring and Out,” which was surprisingly well received. With the book, Johnson, in effect, printed his own legend. In 1946 he was driving to New York for a Joe Louis fight—Johnson, jealous of the second black man to win the heavyweight title, derided Louis’s abilities and enjoyed baiting him from ringside. He crashed his Ford into a light pole near Raleigh, N.C., and was pronounced dead at 68.

The coroner cited “shock” as the official cause of death. One of Johnson’s longtime pals told reporters, “That just can’t be right. Nothing in this world could have shocked that cat.”

But the Johnson legend was just getting started. In an era of burgeoning black consciousness, he evolved into the kind of folk hero that he never aspired to in life. In 1967, Howard Sackler’s play, “The Great White Hope,” with a powerhouse performance by a perfectly cast James Earl Jones as black heavyweight Jack Jefferson, made its debut, and in 1970 was adapted into a much-honored film.

A year later, the coolest black man on the planet, Miles Davis, released “Jack Johnson” (later reissued as “A Tribute to Jack Johnson”) as the soundtrack for a documentary.

Unless, that is, the coolest black man on the planet was Muhammad Ali. Ali sometimes sounded as if he thought he was the reincarnation of the first black champ: “I am Jack Johnson!” he was fond of saying. No, he wasn’t. Ali was persecuted for his association with a controversial black separatist group, the Black Muslims, and for his political views, especially his refusal to be inducted into the armed forces during the Vietnam War.

Sylvester Stallone’s bid for a Johnson pardon wasn’t the first. The bell for the first round was rung by Ken Burns, whose definitive 2004 documentary, “Unforgiveable Blackness,” would air on PBS. Sen. John McCain and Rep. Peter King proposed legislation to encourage President George W. Bush to issue a pardon. Bush showed some interest and then backed off. In 2016, the 70th anniversary of Johnson’s death, in a bipartisan effort, McCain and Harry Reid petitioned President Obama. Perhaps wisely, Obama took a pass.

Not that the Mann Act rap on Johnson ever had much credence. Gerald Early, chairman of Black American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis and editor of, among other books, “The Muhammad Ali Reader,” says, “I think it is fine to pardon Johnson. It was obviously a racial[ly] motivated prosecution that was done under a very poorly conceived piece of legislation. But there were other questionable or debatable prosecutions under the act that should be looked into as well, Chuck Berry’s for instance. In as much the law is an example of federal overreach and has clearly not done well what it was purported to be trying to do—namely, protect women from [being] prostituted—probably many who were imprisoned under the act should be pardoned.”

So Jack Johnson is now, officially, an innocent man. Good for him. Yet every American president from FDR to Trump (including Richard Nixon, who coaxed Jackie Robinson into the Republican Party) have failed to exonerate a far worthier man, Joe Louis. Louis held the heavyweight title for more than 12 years, 1937-1949, and defended it a record 25 times. But bad management, bad investments and terrible spending habits—not to mention an easy mark for friends and family members with their hand out—put him in deep trouble with the IRS over the last 30-odd years of his life.

Louis never went to jail for it, but it was a cloud hanging over his head, even though he cut a deal with the IRS that left him income to live on. But for a while, one of the greatest champions ever was reduced to refereeing wrestling matches for a living. This was a man who flew almost 80,000 miles to box exhibitions for American troops during World War II, demanding only that audiences be integrated, and was awarded the Legion of Merit for donating entire purses to Army and Navy relief funds.

This was a man who, in 1938, on the eve of World War II, had millions of Americans, black and white, rooting for him when he knocked out German champion Max Schmeling in the first round of their rematch.

He did more to bring black and white Americans together than any African-American up to his time. Yet the image of Joe Louis, caught almost exactly between the two dynamic careers of Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali, has faded. It’s due for a revival, and that might begin with a symbolic exoneration of his tax penalty. It would do Louis no more tangible good than a pardon would for Johnson. But it would once again put Louis’s story where it belongs—at the center of American sports culture.

When Louis lost his first fight with Schmeling in 1936 in New York, African-American men openly wept on the streets of Harlem. Some suffered heart attacks listening to the fight on the radio. Lena Horne, performing at a night club that evening, broke down when she heard the news. Her mother reproached her, “You don’t even know the man.” Lena replied that she didn’t have to know him: “He belongs to all of us.”

And so Joe Louis does, then and now. Much more so than Jack Johnson, who never really belonged to any but himself.

Johnson did get a bum rap on the Mann Act, but the Jack Johnson whose brand Republicans want is the Johnson character of “The Great White Hope,” the man anointed by Miles Davis and Muhammad Ali. That man never existed in real life, and if Barack Obama had pardoned Johnson, you can bet Fox News would have revived the real Johnson and screamed bloody murder.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to note that Johnson fought Langford when they were both challengers for the heavyweight title.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.