Pricey IVF Test May Be Selling False Hope

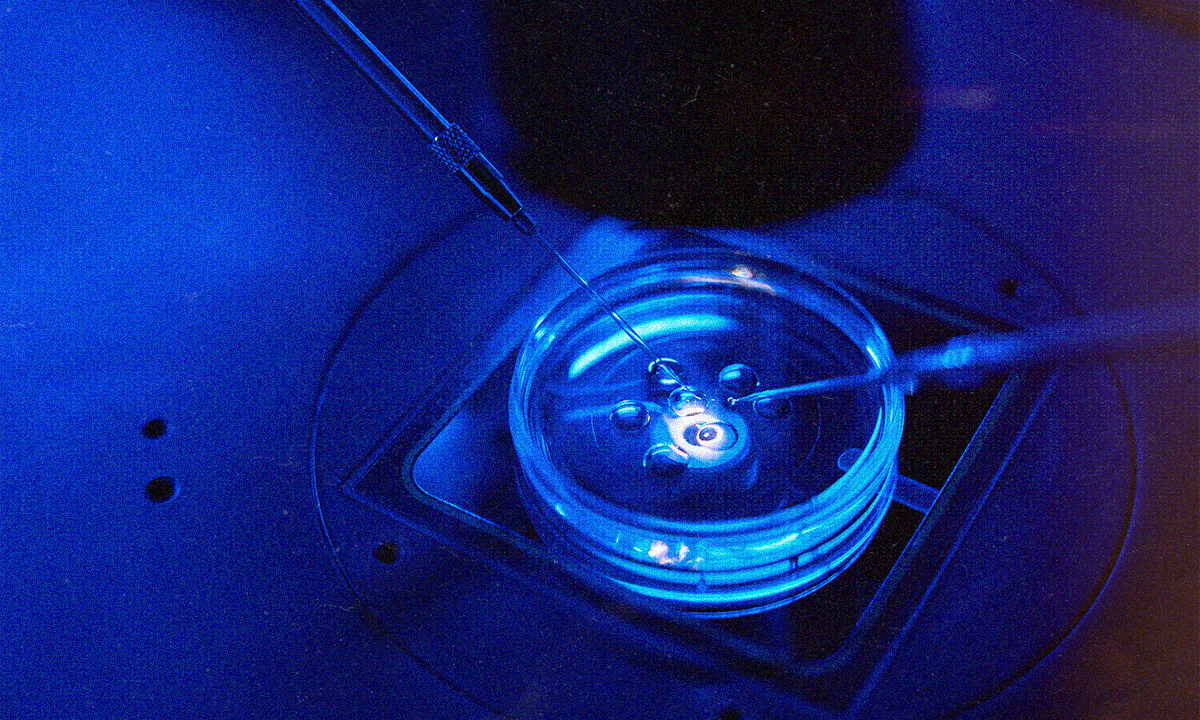

A series of class-action lawsuits are challenging a popular IVF genetic test that many say is worthless. Are PGT-A tests selling a lie to women seeking in vitro fertilization? (Image: Adobe)

Are PGT-A tests selling a lie to women seeking in vitro fertilization? (Image: Adobe)

This article is being co-published with The Lever, an investigative newsroom. Click here to get The Lever’s free newsletter.

After six years of suffering from infertility that doctors couldn’t explain, Michelle R. was ready to take more desperate measures. She had already given birth to two sons who were conceived naturally, but now, at 32 and yearning for a third child, she began in vitro fertilization at a Texas clinic.

There, reproductive endocrinologists stimulated her ovaries with hormones to produce many eggs that would then be fertilized in a lab with her husband’s sperm. The resulting embryos would be returned to her womb where, with luck, one would develop into a viable pregnancy and a healthy baby.

Success in any pregnancy depends on the embryo, and the fertility doctors at Michelle’s clinic strongly advised her to opt for an increasingly popular add-on procedure called Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy, or PGT-A. For an extra fee, the IVF clinic would send her embryos to a special lab for testing to determine if they were chromosomally normal (euploid) and likely to result in healthy pregnancies, or chromosomally abnormal (aneuploid), which would probably result in miscarriage or a baby born with certain disorders, many incompatible with life.

“The doctors said that PGT-A would give us a better chance of success, and a better chance of resulting in a healthy baby,” said Michelle, who, like several other women quoted in this story, asked that her last name not be used, to protect her privacy.

The procedure can cost over $1,000 per embryo.

But the procedure isn’t cheap, and it isn’t certain. PGT-A can cost over $1,000 per embryo, on top of the price of an IVF cycle, which averages more than $23,000 in the United States. In an opinion published in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics in January, experts estimated that young, healthy women can spend as much as $280,000 repeating tests to secure a 75% to 90% chance of finding a viable embryo. Older women may spend as much as $450,000.

“We felt pressured into doing it,” Michelle said, but she remained hopeful that the procedure would finally give her another healthy child.

That is not what happened.

Michelle is one of nearly 700 people and counting who have joined a set of six class-action lawsuits in at least five states filed against the companies providing PGT-A testing for selling false hope. Plaintiffs allege that they have suffered financial and emotional harm after being pressured to undergo a costly and unproven test that led some to discard their potentially viable embryos. Others believed they were guaranteed better outcomes with PGT-A, which is becoming an increasingly common procedure in a field consolidating under private equity and corporate investment, and are pushing for more regulation and transparency within the IVF industry.

Michelle said her doctors retrieved 22 eggs from her as part of the IVF procedure. After fertilization, six made it to the stage where they became suitable for PGT-A testing and were sent to a lab. There, the test determined that four of Michelle’s embryos were normal.

She became pregnant after her first embryo transfer but miscarried at 9 1/2 weeks. The clinic told her the miscarriage was probably due to a chromosomally abnormal embryo, which left her wondering: “What was the point of testing the embryos if you’re going to say the embryos were bad either way?”

On subsequent attempts, the second and third transfers did not result in pregnancies, and the fourth embryo that tested as normal resulted in her son. But he was born with a rare genetic disease called X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. The genetic disorder, which affects the nervous system and adrenal glands, was detected on newborn screening and can cause seizures, deafness and a rapid decline into a vegetative state about two years after nervous system symptoms develop.

Now, she must spend money out of pocket for her son’s genetic labs every three months and sedate him for an MRI every six months — exactly what she thought she was avoiding when she signed up for PGT-A. Children born with this condition generally have a life expectancy of just a few years.

“They knew how badly we wanted another child,” she said. “They sell this PGT-A testing like it’s the end-all, be-all; like it is going to help you have a successful, healthy baby.”

Alleged deception

We all begin as embryos, and, if we’re healthy, each of us has 23 pairs of chromosomes, one of which determines our sex. But sometimes an egg and sperm combine to create an embryo with too many or too few chromosomes. These chromosomally abnormal embryos account for the majority of first-trimester miscarriages. Others can implant in the uterus and develop into a baby with birth defects including Down syndrome.

In PGT-A testing, embryologists remove some cells from the embryo that has become a blastocyst (a cluster of dividing cells that forms about five to six days after a sperm fertilizes an egg) and test it to see how many chromosomes the embryo contains. Proponents of PGT-A say that embryos with the correct number of chromosomes can be transferred to a woman’s uterus in hope of a successful pregnancy. Today, many clinics consider PGT-A standard care: It is included in about 60% of IVF treatments, according to one recent study, and some clinics do not present patients with a choice in the matter.

In consultations and marketing materials, many IVF clinics promote PGT-A’s ability to reduce the risk of miscarriage and improve live birth rates. On its website and in advertising pamphlets given to potential patients, CooperGenomics, one of the companies named in the new lawsuits, touts its PGT-A test as a way to help “eliminate subjectivity and improve accuracy.”

“Defendants have known for years that PGT-A testing is significantly less than 97 percent accurate.”

The hundreds of women who have joined the lawsuits allege that testing companies have deceived patients by marketing PGT-A with promises of high success rates and healthy babies, despite a lack of research confirming those claims. So far, three law firms have filed six lawsuits targeting several PGT-A testing providers, including the Cooper Companies and its subsidiaries, CooperGenomics, CooperSurgical, as well as Reproductive Genetic Innovations, Progenesis, Natera, Igenomix and Ovation.

“Defendants have known for years that PGT-A testing is significantly less than 97 percent accurate,” one of the lawsuits states. “Despite this, defendants have affirmatively misled patients with their false and deceptive marketing and advertising in exchange for the opportunity to reap millions of dollars in profit each year from selling PGT-A testing.”

The plaintiffs are alleging they have suffered financial and emotional harm: Some patients felt pressured to discard their only embryos based on test results while others believed that they were guaranteed better outcomes by using PGT-A.

Genetic testing is a small but growing slice of the ballooning IVF industry.

PGT-A was developed in the 1990s and became the most common IVF add-on service in the U.S. by about 2020. Globally, the pre-implantation genetic testing market was estimated at $700 million in 2023 and is projected to reach $1.2 billion by 2028, according to the industry research firm, MarketsandMarkets. This expansion tracks with the global IVF industry, which is projected to grow from $25.3 billion in 2023 to $43.6 billion by 2033. In the first quarter of 2024, CooperSurgical reported a 12% rise in revenue to more than $310 million.

The companies could not be reached for comment.

Shea P. did not know she had a choice. At 35, she froze 20 eggs. Four years later, her IVF clinic in the San Francisco Bay Area defrosted 10 eggs and fertilized six embryos, which were automatically sent for genetic testing.

“Testing seemed to just be a given, even though my insurance wouldn’t cover it,” Shea said. “It wasn’t really optional.”

Out of the six embryos Shea’s doctors sent for testing, only one came back normal. As someone with an advanced degree in neuroscience who describes herself as “fairly comfortable reading papers and looking at data,” she found that to be odd. She says she believes that, statistically, half her embryos should have come back as normal.

“Me and my partner clearly make relatively strong embryos,” she said, citing their child from a natural pregnancy when she was 36. “It didn’t make a lot of sense to me that only 1 out of 6 blasts came back as normal.”

“Testing seemed to just be a given, even though my insurance wouldn’t cover it.”

Per its procedure, her clinic transferred the one embryo that tested normal and discarded the other five abnormal embryos. (Only a few clinics in the U.S. will transfer embryos that PGT-A flags as abnormal.) Shea rues the fact that those embryos were discarded. Although she had signed off on the clinic’s protocol at the time, she said she wasn’t aware of how few normal embryos the process would produce. Had she not tested them, she likely could have transferred them.

Prior to undergoing PGT-A testing, her embryos had been graded based on their morphology, or physical structure, under a microscope to determine which looked the best for transfer — a standard procedure at IVF clinics, even though PGT-A essentially supersedes this morphological grading. As a result, “I basically threw away five ‘good’ graded embryos because of testing,” Shea said. Ultimately, the one “normal” embryo did not result in a pregnancy, and, questioning PGT-A’s accuracy, she decided to fertilize her 10 remaining frozen eggs without testing them. She has reported an early pregnancy from her untested embryo.

Shea has joined the class-action lawsuits to recoup her testing costs and protect other women. “I think what [PGT-A testing] is primarily doing is causing women to have to do a ton of extra egg retrievals,” she said, because women often repeat the procedure many times in search of blastocysts for PGT-A. “People hear genetics and genetic testing, and they’re like, ‘Oh, that’s the golden ticket.’ And in this case, you know, it’s really not.”

Another class action plaintiff, Leticia, said she was also coerced into testing — and was effectively handcuffed by the results. “Basically, it felt like they were forcing me to test it,” she said.

When her embryo came back as abnormal, the clinic refused to transfer it, despite her willingness to sign a waiver of responsibility. (The few clinics that will transfer abnormal embryos often require patients to sign a waiver stating they will terminate a pregnancy that would lead to serious birth defects or that is incompatible with life.) Leticia found a clinic in New York that respected her decision and was willing to attempt the transfer.

This cycle resulted in a successful pregnancy and the birth of her child. Thinking of all the discarded embryos that might have proven viable, she said, “There are so many people, so many ladies with broken hearts,” she said.

A scientific holy grail

IVF is an expensive process that can exact an excruciating physical and emotional toll on those who undergo it.

The older the woman is at the time her eggs are retrieved, the higher the chance the embryos will be chromosomally abnormal and not implant, resulting in a miscarriage, stillbirth or a baby born with genetic disorders sometimes incompatible with life. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports the rate of early pregnancy loss in women age 20 to 30 years to be only 9% to 17%, compared to 75% to 80% for women aged 45 years. The risk of Down syndrome, preterm birth, preeclampsia and stillbirth also increase with an older pregnancy. (Older fathers also contribute to birth defects, premature birth and psychiatric disorders.)

That’s why a technology that promises to select the best and healthiest chromosomally normal embryos would be the holy grail of IVF. And PGT-A is just the latest technology in the last three decades to promise this.

Past methods for testing the embryo for chromosomal abnormalities before transfer have evaluated various parts of the embryo using different technologies with names like FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization), Array CGH (comprehensive chromosome screening), NGS (Next-Generation Sequencing) and SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) microarray platforms. PGT-M is used to identify monogenetic (single-gene) disorders for couples that are genetic carriers for inheritable diseases such as BRCA1 or Fragile-X syndrome.

Clinics have adopted new methods until they are proven inaccurate or displaced by the next version. Even today, while most clinics offer — or strongly recommend — PGT-A, the research is divided over the test’s efficacy.

PGT-A is just the latest technology in the last three decades to promise improved results.

In a 2018 study of nearly 9,000 women under age 42 from 78 clinics published in the official journal of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, PGT-A was found to reduce time in treatment by four months and reduce the risk of failed IVF transfers and clinical miscarriages when compared to IVF alone.

“For patients with more than one embryo, IVF with PGT-A reduces health care costs, shortens treatment time, and reduces the risk of failed embryo transfer and clinical miscarriage when compared to IVF alone,” concluded the study’s authors.

And hundreds of thousands of women credit their successful IVF journeys to pre-implantation genetic testing. One of those, Andrea Syrtash, is the founder of “Pregnantish,” an influential online media platform focused on fertility, relationships and family-building journeys.

“Genetically testing my embryos, after years of failed IVF transfers, gave me the clarity to understand that it was my uterus — not our eggs or sperm — that was likely the issue,” she said. Her first cousin was the surrogate who carried their genetically tested healthy embryo. “We finally met our baby,” Syrtash said of her daughter, who is now 6 years old.

But a 2021 study on women in the New England Journal of Medicine came to the opposite conclusion. In this randomized control study of 1,212 women age 20 to 37 with three or more blastocysts, live births occurred in 77.2% of women who underwent PGT-A and 81.8% of those who did not.

In September, findings like these caused the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, a nonprofit organization that develops ethical and practical guidelines for reproductive medicine, to reverse its earlier support of PGT-A, saying that the science does not support it. “The value of PGT-A as a routine screening test for all patients undergoing in vitro fertilization has not been demonstrated,” stated the organization, whose members include 90% of U.S. fertility clinics.

In a committee opinion, the organization noted that despite earlier studies reporting higher live birth rates after PGT-A, more recent randomized control trials “concluded that the overall pregnancy outcomes via frozen embryo transfer were similar between PGT-A and conventional in vitro fertilization.”

Significant financial interests

Despite the conflicting research, a steadily increasing number of U.S. clinics present PGT-A as part of the best way to do IVF, and the portion of U.S. clinics encouraging the test exploded from 11.4% in 2016 to 44% in 2019. However, although women considering PGT-A often find that fertility doctors at large clinics recommend it, many others, including Dr. Norbert Gleicher, founder and medical director at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York, harbor deep reservations.

“The argument that any test would improve the chances of live birth, just from the beginning, was nonsensical, but it sounded good,” Gleicher said. “It doesn’t make sense to spend an extra $5,000 on something to get a minimal difference in only a small selected subgroup.”

Gleicher and others have shown embryos that PGT-A flags as abnormal can result in healthy children. Their 2019 study published in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics found that of the 20% of clinics that transferred so-called abnormal embryos, almost half (49%) resulted in ongoing pregnancies or live births. “These data further strengthen the argument that PGT-A cannot reliably determine which embryos should or should not be transferred and leads to disposal of many normal embryos with excellent pregnancy potential,” the study’s authors explained.

The portion of U.S. clinics encouraging the test exploded from 11.4% in 2016 to 44% in 2019.

Although PGT-A is marketed as a tool for clarifying the IVF process, deciding whether embryos are normal or abnormal is not as black-and-white as many women are led to believe. Sometimes, embryos are classified as mosaic, meaning they contain both normal and abnormal cells, leading some women to retest their embryos. Meanwhile, doctors have also found that embryos can self-correct a chromosomal abnormality.

So, why do so many clinics still use PGT-A? Gleicher had one word: “Money.”

In recent years, large health care corporations and private equity firms such as Sagard Capital Partners and Lee Equity have been buying up IVF chains across the U.S., investing hundreds of millions of dollars in the booming field. Investors are racing to establish large national chains, forcing consolidation that tracks with trends in the overall U.S. health care system, where nearly 4 in 5 physicians were employees of hospital systems, private equity firms or other corporate entities as of 2023. And, as in fields including primary care, eldercare and veterinary medicine, many patients interviewed for this story say they believe this influence has affected the quality of care. In the case of IVF, patients have claimed the corporate influence has led to increased pressure to undergo new testing and purchase other add-ons.

There is no overarching regulatory agency supervising fertility facilities, and clinics handle the process differently. In a study published in January, Gleicher found that the likelihood a clinic will push for PGT-A testing often depends on its ownership: Private equity-owned fertility clinics, in particular, were 10% more likely to perform PGT-A than those owned by private physicians, universities or the military.

CooperSurgical has reported record revenue in recent years, driven partly by a steady increase in its fertility business. Natera, a testing company targeted in the lawsuits, saw its revenue from 2023 to 2024 jump by 52%. Across the industry, tests that identify chromosomal abnormalities have come to command 46.8% share of the reproductive genetics market.

Gleicher has warned about the potential negative impacts as the fertility field is gobbled up by profit-focused investors and corporations that push expensive tests and run smaller operations out of business, as has already happened in Australia. But many top doctors at large U.S. clinics that offer PGT-A don’t buy the criticism.

“It’s nonsense,” said Dr. James Grifo, director of NYU Langone Fertility Center and a pioneer of genetic testing. “We lose money by doing PGT: We do fewer cycles, and fewer embryo transfers” — because they transfer only normal embryos — “and we do fewer dilation and curettage surgeries for miscarriage, which we get paid to do. The genetics lab gets the test revenue, not us. It generates more work for us explaining results.”

In Grifo’s experience, PGT-A lowers miscarriage rates, which saves patients emotional torment and risky procedures.

There is no overarching regulatory agency supervising fertility facilities.

Last year, NYU performed approximately 3,000 egg retrievals as part of IVF cycles; Grifo said they offer PGT-A for all patients, and they have not had a baby with Down syndrome from a PGT-A tested embryo since 2011. Grifo also discounted studies refuting PGT-A’s efficacy, noting that randomized controlled trials don’t account for differences in quality between clinics, embryo biopsy techniques and embryology labs.

His facility and IVI RMA clinic of New Jersey have transferred 137 embryos that had tested as aneuploid (abnormal) using PGT-A, and none resulted in a live birth, he said.

But the authors of an opinion published in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics in January disagreed, unequivocally: “PGT-A is not beneficial to the infertile couple. PGT-A does not significantly impact the pregnancy rates, the number of children born, the miscarriage rate, or the time taken to achieve pregnancy.”

The authors note that the uncertainty, known drawbacks and high costs of PGT-A “supports reconsidering its use, potentially even banning it. However, any ban on PGT-A is likely to be difficult to implement due to the significant financial interests of the parties involved.”

Seeking transparency

In 2021, Allison Freeman, a managing partner at a Florida-based law firm who had a baby through IVF, found herself fielding unusual calls from acquaintances going through IVF.

Women would tell her they only had one embryo, but then a while later, had none. “What do you mean you have no embryos?” she would ask them. They would tell her their one embryo tested abnormal, and that it’s gone.

“That’s what kept happening, over and over and over,” Freeman said. “And I thought, ‘Wow, this test must be just the most amazing thing on the planet, right?’ If we’re treating it as the end-all, be-all for what we ultimately transfer and don’t transfer.”

After talking to doctors, embryologists and genetic counselors, she grew concerned. “I started realizing the test has very strong marketing claims for what it’s capable of, and everyone feels like they have to do it.”

Freeman herself was one of those people. When she started IVF at age 33 in 2018, the university-backed clinic she worked with did not push genetic testing. It’s up to you, they told her. But by the time she went back in 2021 to undergo IVF for her second child, her clinic had been purchased by Shady Grove Fertility, the largest physician-led network of fertility practices in the U.S., and things had changed.

“We just want more people to know about it so they’re aware.”

She received multiple phone calls with a tenor that she described as: “You’re over 35. How dare you proceed without testing?” as well as a flood of promotional material pushing the test.

“Ultimately, I didn’t end up testing,” she said of her second IVF treatment. “I’m still not really sure why, because I felt like it was pushed so heavily on me.” Freeman now has two daughters, the first through IVF with an untested embryo and the second from a natural pregnancy.

“These [testing] claims are not validated the way that they should be for the broad strokes that they’re marketing,” said Freeman, whose law firm helped file the first lawsuits against PGT-A providers in late 2023 and early 2024.

Besides damages, these lawsuits want changes to industry practices to ensure that patients know PGT-A is optional and imperfect.

“We just want more people to know about it so they’re aware,” Freeman said. “We want transparency.”

The lawsuits do not claim that patients should never test their embryos, but rather that patients should understand the limitations of the test and that clinics should not treat the results as definitive.

“If people are going to test, that’s their decision,” Freeman said. “Go through your journey and then decide.” But, she warned, “don’t discard any of your embryos based on the test’s results.”

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.