‘Prophet’s Prey’ Film Review: This American Horror Story Is All Too Real

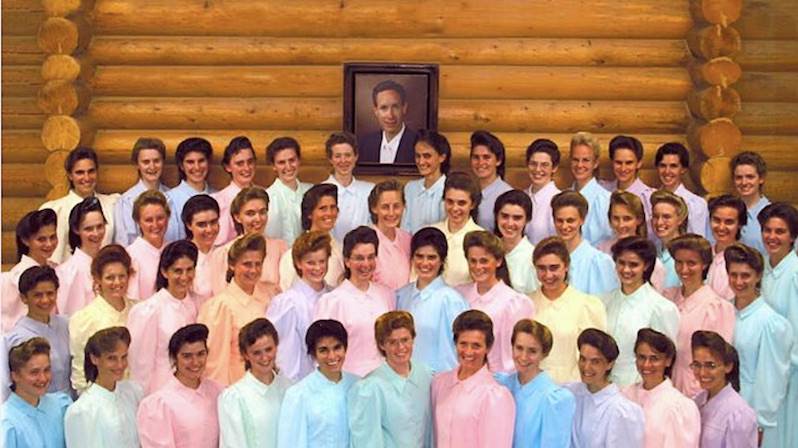

Amy Berg's disturbing documentary on the Warren Jeffs polygamist sect zooms in on a story that oozes with archetypal evil. Members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints gather around a portrait of church patriarch Warren Jeffs in this still from Amy Berg's documentary "Prophet's Prey." (IMDb)

Members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints gather around a portrait of church patriarch Warren Jeffs in this still from Amy Berg's documentary "Prophet's Prey." (IMDb)

News viewers who tuned in to any of the dozens of programs clamoring for their consumption early last week might have glimpsed a peculiar sight. In the midst of the coverage of floods that killed at least 20 people on the Utah-Arizona border, TV reports about a dozen of those lost in the deluge showed women in pioneer dresses wading toward safety. Their attire was monochromatic, anachronistic and suitable for neither hot weather nor high water, their hair swept up into distinctive braid-bouffant sculptures.

That televised drama was not about some old-timey Wild West theme park getting hit by nature’s wrath. As is also the case in Amy Berg‘s subtly disturbing new documentary “Prophet’s Prey,” which focuses on the secluded religious sect to which the women belong, the imperiled female figures on screen in the flood reports are mute, vulnerable and on display. They huddle and struggle together without openly acknowledging the cameras or people around them, a tender herd of wildlife curiosities captured in a rare moment of forced contact with civilization.

We watch them in both instances, but they don’t watch us back, primarily because under their religious tenets they can’t. As members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS), they are taught to be deeply suspicious of “gentiles” and are forbidden to consume media produced by outsiders. In Berg’s big-screen study, viewers are invited to gawk at the women, feel outrage and pity for them, and listen to others talk about them. But we almost never hear them speak from within their community, with the exception of one cataclysmic moment in which a 12-year-old bride is heard but not seen during the wedding ceremony that united her with middle-aged FLDS patriarch Warren Jeffs.

Anyone who has sat through a horror movie is familiar with how effective muteness and helplessness can be in ratcheting up the terror. “Prophet’s Prey” is a horror movie without the special effects. None are necessary.

Instead of all that fictional, flashy stuff, Berg and her crack team of collaborators—including mega-producers Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, “Milk” and “Big Love” scribe Dustin Lance Black, and writer-turned-vigilante-gumshoe Jon Krakauer—have caught hold of a story oozing with just the sort of archetypal evil for which religions like Mormonism claim to offer the anti-venom. And as if things could get any eerier, producers brought in gothic maestro Nick Cave to set 90 minutes of dread to music.

The scary premise at the heart of “Prophet’s Prey” is that fairly simple tactics can be used to coerce large numbers of people to act in ways that strip them of their agency, victimizing them countless times over by following an unholy and dismayingly familiar script. Berg’s film also dramatizes how what is commonly called the individual, a discrete unit with a private mind and will, may not hold up too well when exposed to a certain kind of compelling influence. To think this is a phenomenon specific to the FLDS or to the realm of religion is to miss the broader implications of this documentary, as well as of films like Alex Gibney’s “Going Clear.”

This flock’s blank-eyed and oddly uncharismatic leader, Warren Jeffs, is the alpha wolf in total control of their world. By commandeering a potent mix of warped Scripture and classic thuggery, not to mention the studied use of build-your-own-cult techniques (e.g., sleep deprivation, financial control, threats of excommunication and damnation), he has seen to it that the entire foundation of his FLDS society is built upon abuse and exalts him at the expense of all others.

Jeffs and his supporters are steadfast practitioners of polygamy, which the mainstream Mormon Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) outlawed in the 1890s, causing the sect to splinter off and form settlements in the American West and in Mexico—where they continue to defy LDS and U.S. laws. As viewed through Berg’s lens, life for men in the industrious FLDS developments that Jeffs established is an elaborate long con designed to divest them of their money and manhood by linking success in both aspects to absolute obedience to their leader. For women, it amounts to a lifetime of grooming and captivity in the profane frame of the predator.

Worse, as noted by private investigator Sam Brower, who wrote the book that inspired this documentary, beliefs are very difficult to shake loose once they take hold. Since many of the estimated 10,000 FLDS members grew up within the church, helping them get out—apparently one of the missions of the film—is not a matter of deprogramming the brainwashed faithful. There is no prior emotional or psychological blueprint to which they might revert. Instead, Jeffs’ disciples are following a technically rational course of living that happens to flow from a first principle that others consider crazy: Their leader is a prophet with a direct line to God and the imminent ability to destroy them all. However, throngs of heathen moviegoers can be schooled, and “Prophet’s Prey” sends an urgent distress signal to the outside world. It speaks for those still inside, in part through the testimonies of former believers and current apostates. Whether their combined efforts will help the cause of mass liberation, spark a Waco-esque implosion, or maybe just draw widespread critical acclaim and kudos for the filmmakers, remains to be seen.

Krakauer, for one, is ever determined to nail the bad guy with the help of Brower, his trusty P.I. sidekick. Krakauer’s personal stake in the story was initially thrust upon him in the late ’90s, when he was followed by church members and run out of Hildale, Utah, in unmistakable, this-town-ain’t-big-enough-for-the-two-of-us fashion. From that point, he became more invested, even obsessed, and he and Brower pursued Jeffs by land and air. They eventually helped federal authorities hunt down and trap the FLDS paterfamilias, by then one of the FBI’s 10 most-wanted criminals, on a host of charges including the sexual abuse of children. At the time of his arrest in August 2006, he was living it up, gentile style, in Las Vegas.

So Jeffs is in the slammer, but his followers are not out of danger—far from it. The film’s final act is the most unsettling of all, powerfully showing how the roots of faith often run deepest and grip hardest when devotees are faced with what looks like End Times to them but salvation to others.

Gamely playing the martyr from inside his Texas cell, Jeffs is making sure his latest stories are spun on an apocalyptic axis. For a brief moment, he received transmissions from his conscience, but he’s over that now. He passes memos to his congregation, declaring that he and the Almighty have teamed up to trigger actual natural disasters in even faraway lands—earthquakes and landslides in Japan, for example—causing the deaths of millions.

And who knows? Granted the opportunity to claim similar credit for last week’s floods that thinned his Hildale herd by a dozen—a portentous, biblical-sounding number at that—he could well issue one of his signature catechisms to that effect as a warning to the still-faithful. Considering how the looming figure of Warren Jeffs is responsible for every last detail of members’ lives, in a way he might even be right.

Meanwhile, he is the constant subject of another camera’s gaze in a prison near Palestine, Texas as he eats, rests, scans the news and stands motionless in spells, listening for a divine voice.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.