Public Sector Unions Pin Hopes on Antonin Scalia Going Rogue

The conservative Supreme Court justice holds the key to their fate in a case with blockbuster potential.

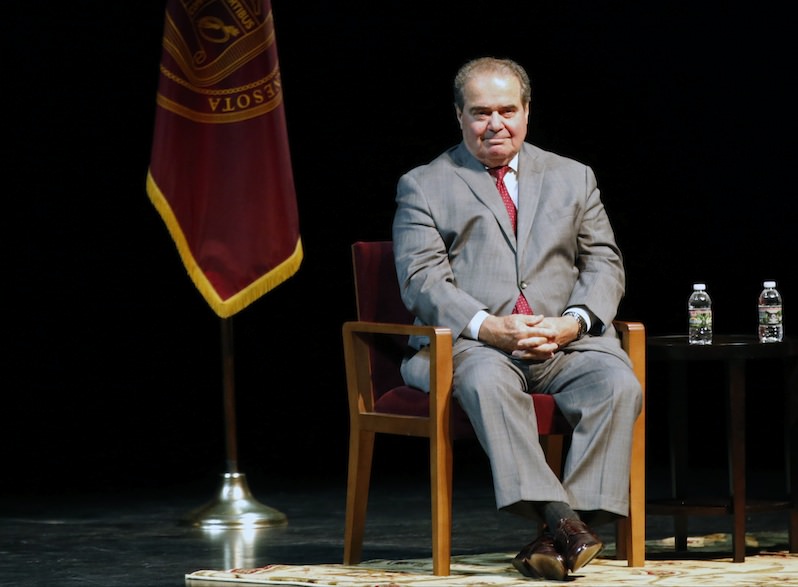

You know that public employee unions are in dire legal straits when their best chance for survival may rest with the Supreme Court’s most volatile, cranky and impulsive conservative: Antonin Gregory Scalia. Yet, according to some very sophisticated, progressive court watchers, that is the exactly the situation in the latest assault on public union operations, in the case of Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association (CTA).

Argued before the justices Monday, Friedrichs concerns the right of unions to collect limited “fair-share” fees from nonmember employees in lieu of full formal dues to help defray the costs of collective bargaining.

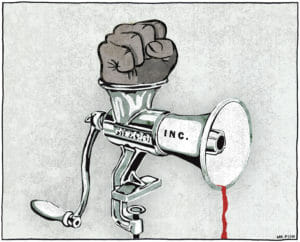

By any yardstick, the case packs blockbuster potential, both legally and politically. A decision against the 325,000-member teachers association could harm every government employee union in the country, draining their coffers and conceivably sending some into bankruptcy. In the process, the nation’s entire public sector would become one uniform right-to-work jurisdiction.

To understand why some observers believe that Scalia, who rarely aligns with liberal causes, might play the critical role of swing voter in Friedrichs, a little digression is required, but rest assured: We’ll get back to him.

The plaintiffs in Friedrichs are the Christian Educators Association International and 10 anti-union California schoolteachers, including lead litigant Rebecca Friedrichs, who has taught kindergarten through fourth grade for nearly three decades in Orange County. They object to paying fair-share fees to the CTA. All were once CTA members but have since resigned.

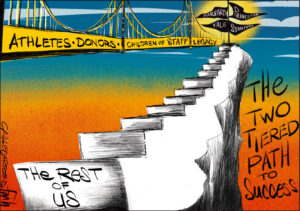

Collectively, the plaintiffs are represented by the Center for Individual Rights (CIR), a nonprofit, ultra-right-wing law firm in Washington, D.C., that has made a name for itself in suits opposing affirmative action, the Voting Rights Act, Obamacare and the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now. According to SourceWatch.org, the CIR is funded by many of the American right’s big-money patrons, such as the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation and the Koch brothers’ Donors Trust network.

Although the CIR handles much of its docket with its own in-house counsel, it has teamed up on Friedrichs with conservative super-lawyer Michael Carvin of the powerful Jones Day law firm.

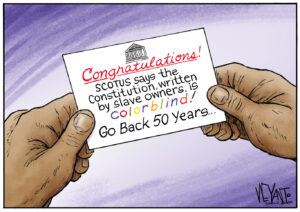

Carvin and the CIR contend that collective bargaining in the public sector is inherently political and that, as a result, the fair-share system violates the First Amendment rights of nonunion workers. The amendment, they note, protects not only the affirmative right to speak without governmental interference, but also the passive right to not be compelled by government to speak or endorse the offending speech or acts of other individuals or groups. Requiring dissenting employees to pay fees to a union they don’t want to join, their analysis continues, amounts to such compelled speech and must be declared unconstitutional across the board.

To carry the day, however, the plaintiffs will have to persuade a majority of five justices to overrule a landmark 1977 decision dealing with government unions, one handed down long before any current justice’s tenure on the court began—Abood v. Detroit Board of Education—which upheld the constitutionality of fair-share arrangements.

This is where Scalia enters the picture.

Prior to the oral arguments in Friedrichs, Chief Justice John Roberts, along with Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Anthony Kennedy, clearly seemed poised to jettison Abood, based on their prior voting records in cases on the fair-share question. A close reading of Scalia’s previous pronouncements on Abood, however, suggested that he might not be ready to fall in line, at least not entirely.

Oral arguments are sometimes poor barometers of how the justices ultimately will vote. Sometimes they play devil’s advocate, and sometimes they ask questions because they haven’t yet made up their minds. But the court’s nine members appeared to divide sharply along familiar ideological lines in the Friedrichs hearing, with the panel’s Democratic appointees supporting the CTA, and its five Republicans—including Scalia—siding with the plaintiffs.

Justice Kennedy remarked during the arguments that fair-share fees “are matters of public concern” and amounted to “coerced speech.” Dissenting employees, he charged, are “being silenced” by being forced to pay them.

Scalia, while not tipping his hand, was described by New York Times reporter Adam Liptak, who attended the session, as “consistently hostile” to the union. “The problem is that everything that is collectively bargained with the government is within the political sphere,” Scalia said from the bench, echoing the CIR’s request to overrule Abood.

Under Abood and other provisions of current labor law generally, no one can be forced to join a union, even one that has been selected by a majority of workers to negotiate on their behalf. States are also free to enact right-to-work measures, as 25 have to date, prohibiting unions from demanding fair-share fees from nonmembers. But because of Abood and other cases decided in succeeding years, in non-right-to-work states like California, fair-share fee arrangements are lawful in the public sector (as they are privately), and they are mandatory once a union has been duly elected.

In fair-share venues, dissenting nonunion workers typically are billed in the form of payroll deductions for full regular union dues. They then have the right annually to “opt out” of making full payments, remitting instead only the portion that is needed to match the union’s bargaining expenses. Fair-share fees (also called “agency fees” in reference to the union’s status as the sole agent authorized to act on bargaining) cannot be used to pay for other union expenses, such as contributions to political campaigns and most lobbying.

As Abood recognized, the fair-share system is designed to equitably distribute the cost of union activities among those who benefit. The system is also aimed at countering the incentive that employees might otherwise have to become “free riders” who refuse to contribute to unions while reaping the advantages they bring, including higher wages, pensions, health insurance, and assistance with workplace grievances and employer disciplinary hearings.

The free-rider problem is real and significant. In California and most other jurisdictions, even in right-to-work states where unions operate, unions have a duty to represent and enforce the contractual rights of all employees in a bargaining unit, both members and nonmembers alike.

Such services don’t come cheap. The fair-share fee for the estimated 9.7 percent of California teachers who, like Rebecca Friedrichs and her co-plaintiffs, have opted not to join their union comprises about 68 percent of full membership dues.

There is little question that in return they receive a handsome payout. According to figures compiled by The Century Foundation, unionized teachers on average earn an hourly wage 24.7 percent higher than their nonunion counterparts.

Should Friedrichs and her cohorts prevail in their quest to topple the fair-share system, more teachers no doubt would leave the CTA, reasoning that they could retain the gains of union contracts without paying a dime for them. Public employees in other occupations probably would do the same, believing that they too could free ride without adverse consequences.During the oral arguments, attorney Carvin sought to assure the justices that the loss of fair-share fees would have a minimal impact on union membership. The evidence, however, shows that he is dead wrong.

If the recent labor strife in Wisconsin is any bellwether, a plaintiffs’ victory in Friedrichs could be disastrous for unions and the benefits they deliver. In the aftermath of Gov. Scott Walker’s 2011 assault on public unions and the state’s subsequent implementation of right-to-work policies, for example, the declines in public union membership and dues collected have been monumental.

The Madison local of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees has lost 18,000 of its previous 32,000 members and has seen its annual revenue fall from $10 million to $5.5 million. The state’s largest teachers union, the Wisconsin Education Association Council, has lost more than a third of its members. As the Wisconsin experience shows, free riding isn’t free.

For all the loopy phrases in his recent court opinions—“argle bargle,” “jiggery pokery,” “pure applesauce,” to invoke just a few—and notwithstanding his regressive positions on such issues as gay marriage, Obamacare, the Second Amendment, affirmative action and voting rights, Scalia in the past has expressed a distaste for free riders.

In 1991, in a case (Lehnert v. Ferris Faculty Association) involving the relevance of the Abood decision to a small Michigan state college, Scalia penned an opinion in which he found the fair-share system served a compelling state interest in workplace regulation, declaring:

Our First Amendment jurisprudence … recognizes a correlation between the rights and the duties of the union, on the one hand, and the nonunion members of the bargaining unit, on the other. Where the state imposes upon the union a duty to deliver services, it may permit the union to demand reimbursement for them; or, looked at from the other end, where the state creates in the nonmembers a legal entitlement from the union, it may compel them to pay the cost.

But that was 25 years ago. The question now is whether Scalia will remain consistent or join with the court’s other conservatives to end the fair-share system once and forever. Those who hope for consistency can point to other areas of the law—for example, Fourth Amendment privacy issues—in which Scalia, despite amassing an enormously right-wing record overall, has displayed occasional maverick tendencies.

Should the maverick Scalia reappear in Friedrichs when the opinion is finally handed down, there will be ample grounds for rejecting the plaintiffs’ First Amendment analysis. In addition to affirming the compelling purpose of the fair-share system, the court, with Scalia as the fifth swing vote, could recognize that union dissenters like Rebecca Friedrichs in fact have sustained no substantial First Amendment injuries.

Despite their fair-share payments, Friedrichs and company remain free to speak out against their union and its views. No reasonable person would construe their payment of fair-share fees as an ideological endorsement of the union. Indeed, as the solicitor general has observed in his brief in the case, the inference to be drawn about the beliefs of fair-share employees is just the opposite.

In the end, unfortunately, the pull of party politics may prove too strong for Scalia. In 2012 (Knox v. SEIU) and again in 2014 (Harris v. Quinn), Scalia joined his Republican brethren in 5-4 opinions that chipped away at the fair-share system and criticized but fell short of overruling Abood.

The Knox and Harris cases, however, dealt with more limited issues than Friedrichs. Knox concerned a midyear dues assessment imposed on state workers to defeat two anti-union measures placed on the 2005 California ballot by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican. The Harris case involved Illinois in-home care providers, who were held not to be full-fledged public employees. Both cases were financed and litigated by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation.

Whatever the final lineup of the justices proves to be in Friedrichs, the court’s decision will have profound political ramifications.

Public unions are the last bastion of organized labor in America. In 2014, the percentage of unionized wage and salary workers in the U.S. dropped to 11.1 percent from 20.1 percent in 1983. The unionization rate in the private sector stands at an abysmal 6.6 percent. The public sector, by contrast, boasts an aggregate unionization rate of 35.7 percent.

Unions are also a consistent supporter of Democratic Party candidates and initiatives, spending, according to some estimates, over $1.7 billion on political campaigns in the 2012 election cycle.

The American right has long demonized unions, particularly in the public sphere, falsely blaming them instead of Wall Street and the crippling financial crisis of 2007-2008 for municipal bankruptcies and pension fund shortfalls around the country. Influential segments of the right, such as the Cato Institute, have openly called for public-sector collective bargaining to be outlawed nationwide for all workers, as it has been for schoolteachers in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Texas.

As I’ve written before in this column, the right’s lesson plan is simple: “Kill the fair-share regime and you kill public sector unions. Kill public sector unions and you kill off the labor movement as a whole.” In the end, the only parties left unscathed will be the big-money corporate donors who have bankrolled the anti-union crusade for decades.

Will Scalia buck the tide and come to the rescue of the unions? We won’t know for certain until the court’s term ends in June. In the meantime, don’t count on it.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.