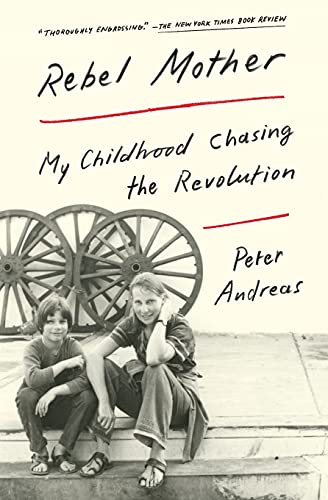

Rebel Mother

Peter Andreas' memoir explores a "childhood chasing the revolution" as the son of an impulsive, self-centered political radical who cloaked her narcissism behind pro-Marxist rhetoric. Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

“Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution” A book by Peter Andreas To see long excerpts from “Rebel Mother” at Google Books, click here.

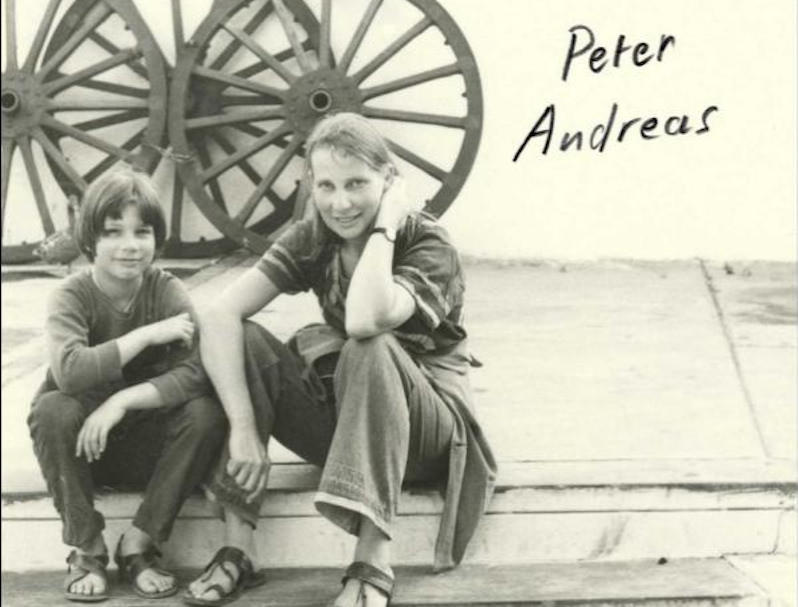

Peter Andreas was the son of a politically radical, impulsive, promiscuous and self-centered mother who cloaked her narcissism and growing depression behind pro-Marxist rhetoric filled with an intensity that left no room for debate. She was a fierce and unyielding ideologue, intolerant of anyone who disagreed with her. Her son’s memoir about their early years together and his most unconventional childhood is a touching meditation, written many years after her death, that struggles to make peace with his troubled memories. The idea for this memoir came to Andreas after his mother’s death as he was cleaning out her home. He uncovered duffel bags filled with letters, poems, notebooks and diary entries. He brought these discoveries home with him hoping to decipher the mystery that surrounded her. She was a complicated and difficult woman, and they had spent the final two decades of her life estranged. Andreas waited 10 years after reading her papers to begin this project. His own late-life entry into parenthood — father to two daughters — seems to have ignited the book.

Andreas is a compelling writer. He tends to withhold his anger, and has a natural elegance and perceptive restraint that allows him to look beyond the surface and examine the underlying factors that motivate people to behave as they do. Perhaps this trait was developed as a child when he had to handle his mother’s emotional neediness and obliviousness to the needs of those around her, including himself. Today he is a professor of international politics at Brown University. He has written 10 books and is well known as a distinguished public intellectual.

His mother, Carol Andreas, was from a small Mennonite town in central Kansas. She married at 17 and there were early signs of her rebelliousness. On the way to the wedding chapel, she told her future husband she was not sure she believed in monogamy, which was radical rhetoric for 1950s Kansas. Andreas’ father was an emotionally cutoff man who spent his career negotiating Social Security and pension benefits for the United Automobile Workers Union. His mother eventually went to graduate school and became immersed in the protest movements that were dominating the headlines. She became an ardent feminist and civil rights proponent and fought against the war in Vietnam, eventually pledging her support for the Vietcong. She stopped wearing high heels and makeup and dressed the part of a bohemian radical. Her husband was horrified by her transformation, but unable to stop her. They were grossly mismatched from the start. Andreas remembers, “The only constant in my life was the indisputable fact that my mother and father were always angry with each other.” She eventually began to support armed struggle against the oppressive forces that were dominating the world’s poor.

Peter Andreas’ life spun wildly out of control when his mother kidnapped him from his elementary school and whisked him and two older brothers away to South America, where she hoped to be part of the revolutionary change stirring in Chile. Her two older children, though still teenagers, quickly set off on their own. Andreas’ father was devastated and tried to regain custody, but this proved to be difficult since the children were out of the country.

One of the most exciting sagas in the book is their arrival in Allende’s socialist Chile in October 1972. Allende had been taking on the rich landowners and foreign companies that owned Chile’s copper-mining industry. He nationalized the copper mines and other major industries, and took over large agricultural estates to distribute land to the campestinos and raise workers’ wages. He established relationships with Cuba and China. Nixon retaliated by supporting Allende’s opponents and squeezing the country economically. The CIA had already tried but failed to block Allende from taking power after he won the election. Andreas remembers a genuine electricity in the air, the sense that real change was possible. But it was soon extinguished. When the military regime overtook Allende, he and his mother fled to Buenos Aires.

Through the many years they traveled around South America, a familiar pattern would emerge. His mother would get involved with younger men who were as intensely chaotic as she was. Andreas as a boy often feared for his mother’s and his own safety. He was witness to Carol’s endless battles with her boyfriends, which would often last all night. He was a witness to her sexual escapades since they usually lived in one rat-infested room without electricity. Sometimes she would leave him for weeks at a time with friends she had made on the fly. He was a hardy, good-looking little boy with an impish face; luckily he made friends easily. He learned how to find sustenance from those he met and stayed with even if it was only for a short time. When his mother returned, they would move on again, and soon she would be caught up in another devastating affair.

Occasionally, one of Andreas’ brothers would show up but leave quickly. His mother had a contentious relationship with her two older boys. They would engage in hours of fruitless debate about who was more loyal to the preaching of Marx, Lenin or Che Guevara. But she clung to Peter, her youngest, like a lifeline, and as she deteriorated, she would confide her suicidal thoughts to him. When his father managed to get Andreas back for a short period through the courts, he enjoyed the tranquility of his father’s home, but was frightened by his father’s remoteness. When his mother wrote him begging him to run away with her again, he was unable to resist. He explains halfheartedly, “My mother’s faith in me was worth sacrificing everything else.” He felt loved by his mother. It was a reckless love, full of destructive impulses, but the only love he had ever known. In his mother’s papers, he found a letter she wrote him. It read:

“To Peter, They say you would be missing something if you were with me. Yes! Missing Alienation. Missing the privilege of having a nice home, family, riches. Missing respect for the terrible laws that bring injustice to the poor. Missing racism that makes one think that women should serve the vanity of men. Missing the pacifism that makes one think the poor should be patient with the rich, waiting for the poor to solve the problems created by the rich themselves. …”

The letter goes on: “We are suffering from the domination by the rich who always punish those who are fighting to change the system. We are suffering from your betrayal my child, because you are very young and you do not yet understand the value of what you have lived.”

When they arrived again in South America, his mother grew more despondent. Her affairs became even more self-destructive. The revolution she sought became more and more elusive. Occasionally, she took part in protests, or volunteered at a school, but she was intolerant of the local customs and rituals she found in many of the villages.

And yet Andreas is intent on finding the good in his mother, and her harshness is countered by his softness. In her papers, he finds a poem that she wrote about him when they were living in Chile:

“Fragile child Far from innocent The other side of me — angry, selfish, curious, insistent. You are my world — everything I am fighting for, everything I am fighting against. Pockets full of candy, eyes full of tears. Don’t give up, don’t give up. You know more than anyone The size and shape of the enemy Your father and mother in mortal conflict Pedrito, my son, don’t forget your mama.”

As Andreas reached high school age, he began to see the cracks in his mother’s armor. He became interested in forging his own path and admitted to himself that he was not at all like her. He was stimulated by debates that probed all sides of an issue. His mother’s rhetoric silenced those around her into an aggravated submission. Andreas contacted his father for assistance with college tuition, going on to earn a Ph.D. from Cornell in government and then on to a stellar career as a professor and writer. His mother viewed his defection as traitorous; their last years were estranged.

But now with the passing of time, Andreas wants to reach out to her again. Of course, she is no longer present except in his memory. He recognizes that despite her faults, she was sincerely trying to teach him about the unfairness she saw everywhere. He regrets that she is not alive to meet his two daughters. And we sense he also regrets that he didn’t reach out to her during her last years. It is incredibly difficult for many of us to make a place in our minds for our mothers in a way that doesn’t rattle us — particularly if our relationship with them was tumultuous and unresolved. They held such power over us when we needed them so badly. Andreas’ book is the story of a sensitive and empathetic man trying to find that place — a place somewhere between forgiveness and acceptance that still embraces reality.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.