Remember the Bear River Massacre, Climax of the American Holocaust

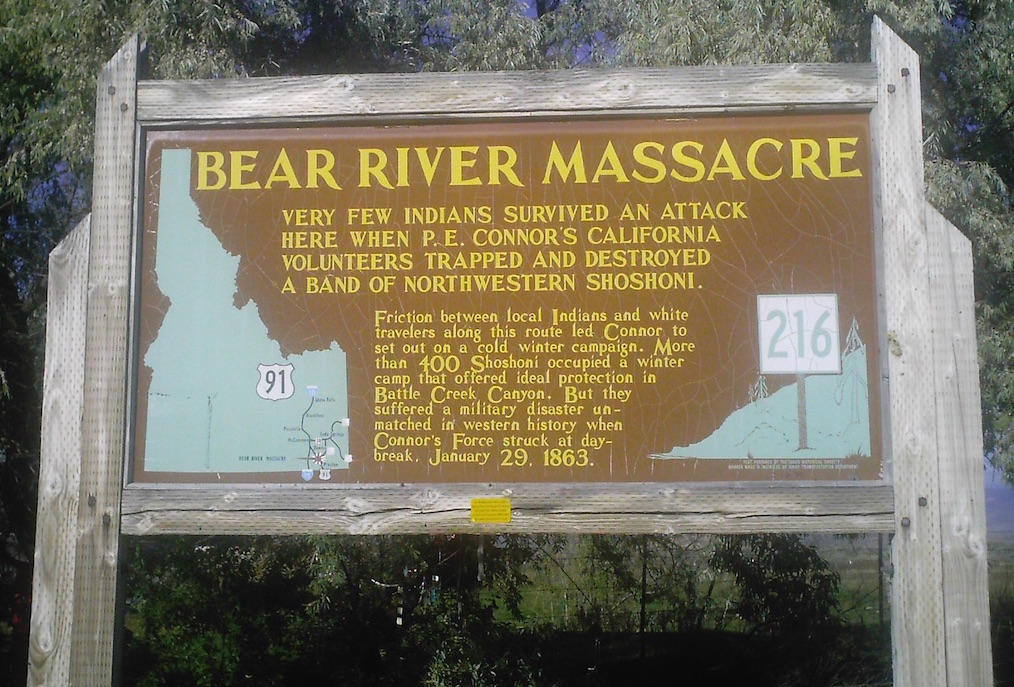

We must never forget. The road to Auschwitz was paved with the blood of Native Americans. Roadside sign on U.S. Highway 91, about three miles north of Preston, Idaho. (Robert Scott Horning / Wikimedia)

Roadside sign on U.S. Highway 91, about three miles north of Preston, Idaho. (Robert Scott Horning / Wikimedia)

On the way to Auschwitz the road’s pathway led straight through the heart of the Indies and of North and South America.

—David E. Stannard, historian and author of “American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World”

Since 2005, the United Nations and its member states have honored Jan. 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The purpose of this day is twofold, says the United States Holocaust Museum on its website: “to serve as a date for the official commemoration of the victims of the Nazi regime” and to “develop educational programs to help prevent future genocides.”

Education to prevent future genocides.

Bloodbath at Bear River

Just two days after International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Native Americans remember the largest and among the least-known massacres to occur on American soil, the Bear River Massacre. On Jan. 29, 1863, United States Col. Patrick Connor and California volunteers attacked approximately 500 Northwestern Shoshone Indians, leaving them bloodied and frozen in the snow, or floating down the crimson red and half-frozen Bear River in southeastern Idaho.

“The Indians tried to defend themselves, but what was an arrow and tomahawk against the rifles and side arms of the soldiers,” wrote Northwestern Shoshone elder Mae Parry, who recorded the testimony of 13 survivors. “The Indians were being slaughtered like wild rabbits. Indian men, women, children and babies were being killed left and right.”

There was no mass grave for the Shoshone after the massacre. The victims were left to the elements, to the crows and the wolves.

There was no official body count, and the recorded number of slain Shoshones range from the earlier estimates of 250 to later estimates of 450 and 490. According to oral stories from one tribal elder who has since passed, the number of deaths was much greater than that. Conversely, the Shoshone managed to kill or mortally wound 24 soldiers in the first hour of the four-hour massacre, before the skirmish turned into an all-out hunt for every remaining Shoshone.

In the same year as the Bear River Massacre, a series of treaties was struck with nearby Shoshone bands. Fearful and suffering their own series of assaults from settlers, tribal historians say, the Shoshone signed treaties “under the gun,” making egregiously lopsided agreements with the United States government.

The Box Elder Treaty was signed in July 1863, with the Shoshone forfeiting two-thirds of their hunting grounds in eastern Idaho. The Ruby Valley Treaty, signed on Oct. 1, 1863, granted the United States the right to cross through western Shoshone territory in northern Nevada with telegraphs, stage lines and railroads and engage in economic activities in Shoshone territory, which eventually meant mining the mountains for silver and gold.

Over a century later, in 1986, and after Northwestern Shoshone descendants of the Bear River Massacre survivors had spent years advocating for a memorial, the legislatures of Utah and Idaho jointly resolved to create a “Battle of Bear River Monument.” But the bloodbath at Bear River was clearly much more than a battle. The surviving Northwestern Shoshone threatened suit to force a shift toward their point of view. Finally, in 1990, after an investigation by historian Edwin C. Bearss, the federal government officially recognized the fight as a massacre, and designated the site as a National Historic Landmark.

Despite this designation, little is known about the Bear River Massacre today, which, according to the Smithsonian Institute, is said to be the deadliest massacre in American history.

Remembering the American Holocaust

The danger lies in forgetting. Forgetting, however, will not only affect the dead. Should it triumph, the ashes of yesterday will cover our hopes for tomorrow.

—Elie Wiesel, Jewish author and professor

I am among the millions who have visited the deeply moving Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. I felt the knots in my stomach walking through the shoe exhibit with piles of thousands of musty leather shoes of all sizes belonging to Jewish victims, standing as a sensory reminder that these were human beings who were exterminated by Hitler’s regime. They had life. They had shoes. They had names.

Their names, their faces and their stories are thoughtfully integrated into the museum experience to remind us of our humanity. All throughout the museum, I felt sick. I was heartbrokenly sick, not simply because of the sheer level of atrocity around me, but because of the forgotten American atrocities that lie beneath my feet.

There is blood beneath the foundation of the Holocaust Museum. There is blood beneath our homes. The American Holocaust is forgotten, and forgotten by design.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said:

Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shores, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles of racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or to feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it.

You see, hunting down human beings—men, women, children and infants—at dawn, and because they were Indian and less worthy of life, because they were an obstacle to settler colonialism, simply does not fit into the lily-white narrative of Manifest Destiny and American exceptionalism. Acknowledging its own genocide of indigenous peoples just does not sit well with America, overall.

Ostensibly, in an attempt to paint and repaint fresh layers of whitewash over American history, our institutions honor and remember international crimes against humanity, feigning complete ignorance of American crimes or outright denying the truth of the American Holocaust. But the truth is found beneath the peeling whitewash.

Bear River. The Dakota 38 + 2. Wounded Knee. Sand Creek. Washita River. Pit River. The Marias Massacre. The heartbreaking list goes on and on. Many more massacres we may never know about.

Indian boarding schools. The involuntary sterilization of Native American women. Missing and murdered indigenous women. Highest youth suicide rates in the nation among Native American people.

All of the social ills of struggling tribal communities today are connected by a common thread, and we must remember and understand why: Indigenous peoples have suffered brutality and compound traumas at the hands of settler colonialists and the United States government, with little to no time or space to heal, no acknowledgment or compassion from the masses, no admission of the crimes which began in 1492.

And on Jan. 27 every year, America honors International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

But we must never forget. The road to Auschwitz was paved with indigenous blood.

In remembrance of Bear River, Jan. 29, 1863. The Shoshone babies and children had faces. They had names, and moccasins. They giggled and smiled. The women, the men and the elders, they had stories, too. They cared for and protected their families. They loved, and they wanted a good life for their people. Remember them. Remember us. We are still here.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.