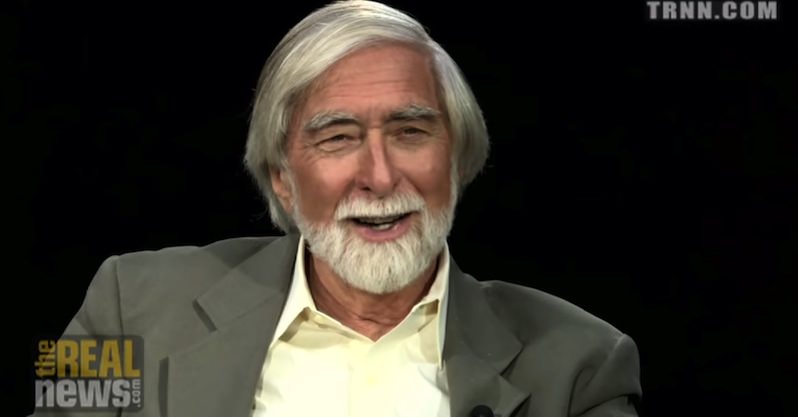

Robert Scheer: Plundering Our Freedom With Abandon (Part 2 of 10)

Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer and The Real News Network's Senior Editor Paul Jay discuss the inherent contradictions in Silicon Valley’s ideology and practices in the second installment of TRNN’s show “Reality Asserts Itself.”

Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer and The Real News Network Senior Editor Paul Jay discuss the inherent contradictions in Silicon Valley’s ideology and practices in the second installment of TRNN’s show “Reality Asserts Itself.”

Also in this second segment, Scheer explains how constitutional principles continue to guide Americans, how he really feels about Rand Paul, and the dark side of the Internet.

“The Internet is incredibly liberating, and I never go anywhere without some kind of little machine,” Scheer says. “So that’s the positive. The downside is, most people don’t ever go anywhere without the little machine, and the little machine, even when you think it’s off, can be controlled by the CIA and the NSA, the FBI, and be spying on your entire family and intruding on your home in violation of the Fourth Amendment, without a warrant, and can see where you ate and who you ate with and correlate it with other data, and because of cheap storage space and massive, powerful computers, can do biometric comparisons. And so we have no privacy.” (Transcript follows the video below.)

–Posted by Jenna Berbeo

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. We’re continuing our interview with Robert Scheer, who joins us again in the studio. Thanks for joining us.

PROF. ROBERT SCHEER, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: Thank you.

JAY: And one more time, Bob Scheer is a veteran U.S. journalist, currently editor-in-chief of the five-time Webby Award-winning online magazine Truthdig. And Bob’s whole biography you’ll find below the video player here. Well, you can–.

SCHEER: Let me defend–in our first segment together, we wandered quite a bit, from my mother arriving from Russia.

JAY: We haven’t done much on your father yet, so we’re going to pick that up.

SCHEER: Yeah, and who was a great guy, and from my mother arriving from Russia. And then we ended up at Palentir and Silicon Valley and the military-industrial complex. I guess that’s kind of a long-winded answer to your question of where do I get my inspiration or my ideas. You know, I’m still at work.

JAY: More than that, your whole career is taking on very challenging, controversial, sticking-your-neck-out topics. So it’s all about, also, that.

SCHEER: But also complex topics. I like figuring stuff out. I find it intellectually stimulating. I’m not bored. And so the example I used in our last interview, I just–the morning of our interview, I’m reading, you know, the news at four in the morning ’cause I can’t sleep and, you know, when the whole–the secretary of defense is in Silicon Valley, gave a speech at Stanford. And I said, wow, that triggered thoughts about my own book and things I may have missed or things I would add to the next edition. And particularly, in our last discussion, we were talking about a speech he gave, the Sid Drell Lecture at Stanford, and he was boasting about the close connection between the Pentagon and the intelligence agencies and Silicon Valley companies. And he offered the example of In-Q-Tel, a company that was founded with CIA support. And the CIA was–In-Q-Tel was–Palantir, one of the companies spun off by In-Q-Tel, was their client, their only client for the [crosstalk]

JAY: Yeah, so you’ve get this problem of Silicon Valley is making tremendous amounts of money cooperating with the government in all this, and you’ve got this kind of libertarian thread, we’re told, within their ideology and outlook.

SCHEER: Oh, that we’re self-made people in all we do. And there’s a contradiction, by the way. That’s what my book is all about, this contradiction, that–first of all, let me–.

JAY: Let me just remind everybody, this is–the book Robert’s talking about is They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy.

SCHEER: Yeah. And let me apologize. I’m usually the interviewer, so maybe I’m playing that role also, interviewing myself.

But first of all let me say I’m really not that interested in my own history. And I’m very interested in where we are now. You know, yes, I’ve done a lot of real, you know, I think, interesting, important, blah blah blah blah blah. But I get kind of bored thinking about it. And I’m now 79 years old, and maybe I should be sitting on some retirement funny farm thinking about [crosstalk]

JAY: Thinking about the old days.

SCHEER: Yeah, but they weren’t–you know, and I think these days are more exciting.

And let me explain, by the way. I love the internet. I love the new technology. I’m not a Luddite. I have to say that. I run an internet publication. I’ve done it for over nine years now, and we’ve won a lot of awards. I love the technology. I’m an early adopter to everything.

For one thing, when growing up, they didn’t use the language of learning disabilities or differences or dyslexia or anything, but I had a pretty pronounced case, and I had a hard time with cursive, I had a hard time with spelling. And as a result I ended up studying engineering, because I really had a hard time writing essays and so forth. And I have a son, my son Josh, who has been the major researcher on my books–invaluable to me and, you know, really smart, but he has had an even more severe learning difference, and was even a student at USC where I teach. When I was there, he did better than his brother, who didn’t have any [incompr.] So I’ve dealt with those kind of issues of how do we learn, yes.

JAY: We were starting to dig into the contradictions in Silicon Valley and libertarian–. Yeah.

SCHEER: No, I was explaining why I’m an early adopter on the internet, and it relates to Silicon Valley. I’m a big fan. I interviewed Bill Gates for Talk magazine, and we both talked–I said my only criticism of Microsoft is you didn’t have spell check on your first programs and how I had to go out and buy an IBM display writer, and it cost me $35,000, my entire book advance, in order to have spell check and all this stuff. And he laughed and he brought in the guy who wrote his spell check program. So I am not against the technology. For someone with my learning issues–and I’ve talked to the founder of Kinko’s, I’ve talked to plenty of people with learning issues who are successful, and we all agree this technology has been incredibly liberating. So I only could become a writer because of computers.

JAY: Yeah, same with me. I can’t spell.

SCHEER: Well, it’s not just the spelling. It’s the ability to move, organize. You know, my mind goes, often, as you can tell, in a lot of different directions. And so it’s been a great boon. And having the internet so you don’t have to have a major library and live in New York or Washington, you could be in Podunk and still read original documents and do your own search–the internet is incredibly liberating, and I never go anywhere without some kind of little machine. Okay? So that’s the positive.

The downside is most people don’t ever go anywhere without the little machine, and the little machine, even when you think it’s off, can be controlled by the CIA and the NSA, the FBI, and be spying on your entire family and intruding on your home in violation of the Fourth Amendment, without a warrant, and can see where you ate and who you ate with and correlate it with other data, and because of cheap storage space and massive, powerful computers, can do biometric comparisons. And so we have no privacy. And we can discuss that, ’cause that’s what my book is about, without privacy.

JAY: Well, isn’t part of the problem here is that libertarian philosophy embraces as one of its core principles the right to private ownership and the virtue of for-profit enterprise, and when that gets into the area of data and working with the government, the for-profit character of the enterprise trumps the libertarian ideology.

SCHEER: That’s only if you’re a sellout libertarian. If you’re libertarian, of which we have many people, you believe in a free market, you don’t believe crony capitalism, you don’t believe in big market-dominating cartels or monopolies.

JAY: Until perhaps you own one.

SCHEER: Well, that’s–I’m not here to defend–.

JAY: No, but I’m asking, is there any libertarian in Silicon Valley that actually puts those principles ahead of–.

SCHEER: Yeah, it depends what you mean by Silicon Valley. But I can tell you, when you go to Stanford, you will find good lawyers and good consumer advocates–Aleecia McDonald is one of them. I could give you names. But there are plenty of people pushing back, even within Google, within Apple, who believe in a truly free market, so you don’t have something like Facebook. See, Peter Thiel is not one of them. Peter Thiel actually has written about the need to dominate a market. That’s the opposite of what Adam Smith was talking about. The model of capitalism that libertarians are supposed to defend is one in which you don’t have manipulation of the market and so–.

JAY: It’s just completely utopian. It never existed. It’s, like, some idea of, some notion of the past that never happened.

SCHEER: You know, one could attack notions of the left in the same way.

JAY: Absolutely.

SCHEER: Okay.

JAY: Absolutely.

SCHEER: So that’s not as interesting as figuring out what is healthy and good in any of these ideas. So on the left, what is healthy and good is an idea of an equal playing field, at least, of equal opportunity, of public education, of helping people when they’re down so they can get up again, of some social responsibility. That’s why I’m on the left. I’m not a right-wing libertarian. You know, and if I would–previously I’ve said I’m a bleeding heart liberal, only liberals have sold out so much I worry about that label. Yet people could attack people on the left and say, wait a minute, it gives rise to totalitarianism. Look at those governments around the world that claim to be socialist. They’re horrible.

JAY: True.

SCHEER: They jail people.

JAY: There’s truth to it.

SCHEER: They torture them. Blah blah blah. So I’m more interested in seeing: are there any good ideas and I think the libertarian ideas, there is something very valuable there. And when you talk to Matt Welch, who’s the editor of Reason magazine or–.

JAY: Who we often do.

SCHEER: Yeah. Well, then I think these are principled people. I thought Ron Paul–I don’t agree with Ron Paul on everything, but I had kind things to say because I thought he was consistent–his criticism of the bailout; he voted against the reversal of Glass-Steagall; he cared about privacy.

JAY: Ron Paul’s been very consistent.

SCHEER: Yeah. Okay.

So what is valuable about that idea–and it relates to my book–is an idea that the framers of our Constitution had, because they were dealing with an economy that basically gave the individual–who was white and male, and we’ll put that already so we don’t have to get a lot of letters about that. It was a flawed society and it was racist and had slavery and so forth. And Howard Zinn was absolutely right and a necessary corrective to anybody who wants to understand the American experiment. And it wasn’t just him. We had Charles and Mary Beard, great historians who stressed the economic inequality and so forth. So there are plenty of people down through the years have showed, okay–.

But there was something brilliant, wonderful, liberating about our Constitution. And that is also embraced by many libertarians. And that’s the notion of limited government, the notion of individual sovereignty, that the individual, right, has to basically be in charge of their feelings, their thoughts, their education, one’s thoughts, one’s education, and that we individuals also need each other and we want to live in societies. And so, for all of the things that John Stuart Mill and Rousseau and everyone else has written about, Bertrand Russell and others, we then cede power to the state in the post-enlightenment idea of the state that was codified more clearly in the American Constitution than any document in human history.

And so the American Constitution is a great gift to human understanding. It’s a great guide. And the heart of it–and I think the assumption of the American [incompr.] which is why we’re running into trouble with people, you know, Citizens United and are corporations money, I don’t think they anticipated monopolistic corporations in the new colonies, ’cause that’s what they were opposing from England, because they assumed they were government-sponsored or government-authorized, right? So if we could keep government out of it, I think they had much more of a rural model of stiffnecked independent farmers and feed, buying their feed, and making decisions, and being politically involved, and understanding their environment, and understanding their needs, and keeping things local, right? The whole idea was very great suspicion of anything national, and avoid foreign entanglements, don’t have big empire. And so you would have a universe that you could comprehend as a farmer or as an urban worker, you know, a craftsman or artisan, and you could comprehend your political questions. Should we widen the highway? Should we bring the water in here? You know, all those decisions. And we have to keep government limited, because power corrupts, absolutely corrupts absolutely. We don’t want Kings. We don’t want [incompr.] And this was a great idea. And it presupposed–the reason I bring up Adam Smith: it presupposed a relatively free market where an invisible hand, meaning no one company could determine prices–.

JAY: They didn’t understand that free market inevitably gives rise to monopoly.

SCHEER: I understand that well, any more than the socialists of their day understood that socialist movements inevitably give rise to a certain totalitarianism manifestation.

JAY: So far.

SCHEER: So far.

JAY: Well, I wouldn’t actually say so far. That’s not even true, because I think in Latin America you’re seeing some variations on that.

SCHEER: Right. So my feeling–and this started at a very early age. I can tell you why. But it actually started during the McCarthy period when I was delivering milk in the Bronx and I was young kid, and people in this project that I lived next to where there were–it was built by the /fo?/ workers union, and so there were quite a few of these sort of lefty worker types there, and people were throwing out their libraries. You know, they were scared. And one day I found the collected works of Jefferson. They were big, green books. Somebody had put a ribbon around it, and there were, like, 20 of them, and it was by the garbage can. And I brought them home. And someone else also brought out the collected works of Stalin, and I think there was even Trotsky.

And anyway, I would collect these books. And I actually took them with me when I went to graduate school to Berkeley and everything. It was my first library were thrown-out books. Okay? And I remember being a big Jefferson fan quite early. And, yes, there are many aspects of Jefferson’s life that are reprehensible. We know that. And Washington’s as well.

But there was a wisdom to these folks, because they saw what empire did to England. After all, they once believed in England, even with the monarchy, and they saw what it did to the English notion of law. They saw how it betrayed the Magna Carta. Okay?

So they came up with two really big ideas. You can’t have a republic and an empire in the same moment. That’s what destroyed Greece. It destroyed Rome. It destroyed any apprehension that you had–not apprehension, but any expectation that you had that a limited monarchy could be reasonable, and generally that the desire to have empire and extend your reach meant that the truth was a casualty, as it is always, of war. It meant that you would not know what’s going on. It was the opposite model to the one we had of agrarian democracy, where the farmer knew what he needed to know politically and you didn’t get this dumb question of I don’t know what’s going on because it’s all classified, and who knows if they have weapons of mass distraction, Iraq or not, but I want to kill those ragheads before they kill me. You know. And you get into stupidity, racism, madness, and in the case of Germany you get fascism; Italy, fascism. So that was one big idea they had of limited government is, if you’re going to be a representative republic, you can’t be an empire. That’s why that constant theme of avoid foreign entanglements, don’t get involved.

If you read Washington’s farewell address, it’s unbelievably clear: use gentle means, force nothing, beware the impostures of pretended patriotism–George Washington’s farewell address that he wrote in collaboration with Hamilton and Madison, that he worked on, as we know, for over five years ’cause he thought he was going to be a one-term president. So George Washington’s distilled wisdom, in collaboration with the key minds of our revolution, was beware the impostures of pretended patriotism. This is from a general, very similar to the warning from general-turned-president Dwight D. Eisenhower about the military-industrial complex, ’cause war makes you crazy, conquest makes you crazy, it destroys what’s decent about the human experience. Big theme.

And the other big theme is the sanctity of the individual. When you travel in totalitarian countries, I don’t care whether you’re left or right, it’s unavoidable. It slaps you in the face. I can tell you I interviewed Fidel Castro–the night that the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia, I was in Cuba. I’ve interviewed leaders in totalitarian societies all over the world. I’ve been there. I’ve written about many of them. And the thing that happens is, if you lose sight that the individual is king and you go down that slippery slope–.

JAY: Hang on. We’re going to keep these sort of in 20 minute segments or so, and we’re going to leave everybody hanging for the next segment. So please join us for the continuation of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.