|

To see long excerpts from “Stokely: A Life” at Google Books, click here.

|

“Stokely: A Life”

A book by Peniel E. Joseph

Throughout the history of the United States, strong African-American men have played dramatic roles in pursuing freedom, dignity, justice and full equality for their people. Many have paid horrific prices, including social ostracism, governmental persecution, media vilification, imprisonment, and the loss of their reputations and even their lives for their relentless and militant commitment to political and moral integrity. Some have become honorable historical icons, serving as authentic role models for all oppressed peoples. Among many others, this select category includes Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Frederick Douglass, Marcus Garvey, W.E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Often — and disconcertingly — missing from this list is Stokely Carmichael, one of the premier civil rights/black power figures of the mid to late 20th century. Peniel Joseph, one of the leading historians of the civil rights and black power movements, puts it bluntly in his new biography, “Stokely: A Life”: “Although today largely forgotten, Stokely Carmichael remains one of the protean figures of the twentieth century: a revolutionary who passionately believed in self defense and armed rebellion even as he revered the nation’s greatest practitioner of nonviolence; a gifted intellectual who dealt in emotions as well as words and ideas; and an activist whose radical political vision remained anchored by a deep sense of history.”

This exceptionally researched and engagingly written book is a comprehensive account of Carmichael’s multifaceted and controversial life as a black and Pan-African activist. The author traces the life of the Trinidad-born Carmichael from his birth in 1941 to his premature death at 57 in Guinea, where he fully implemented his personal and political identity as an African. Professor Joseph details every feature of Carmichael’s political consciousness, which began after his arrival in New York and during his studies at the prestigious Bronx High School of Science.

A highlight of his early political awakening was his friendship with members of the New York left-wing culture, including many young Jewish intellectuals. Like many of his generation, he was reminded of the horrors of racism when he learned of the savage murder of Emmett Till in Mississippi. Carmichael was 14 — the same age as Till — and this event had a huge impact on him. He also found the vibrant tradition of black radicalism, especially in the figure of Bayard Rustin, whose nonviolent perspective and socialist philosophy appealed to his early idealism. Carmichael idolized Paul Robeson, whose militancy and defiant resistance to governmental persecution informed his later radical vision and support of progressive domestic and international causes.

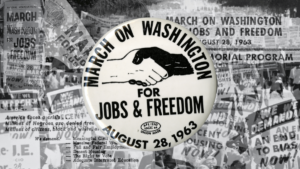

Carmichael commenced his life of political engagement during his studies at Howard University. Galvanized by the historic sit-in at the segregated lunch counter on Feb. 1, 1960, by four African-American students in Greensboro, N.C., and the ensuing civil rights protests throughout the South, he began the political journey that would consume his entire life. This led him to participate in the early freedom rides, landing him in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Penitentiary — the first of many arrests throughout his career of agitation.

The book chronicles Carmichael’s emergence as a full fledged civil rights organizer in the Mississippi Delta, where his personality resonated powerfully with the local black populace. One of the key themes of the book reveals the Stokely that the media typically ignored: Rural African-Americans were impressed and inspired by his intelligence, humor and extraordinary capacity to relate, at deep personal levels, with men, women and children.

As Joseph reveals, being an organizer was Carmichael’s essential personal identity throughout his life. This led to his longtime work and leadership with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and to his efforts in Lowndes County, Ala., where he helped shape the original Black Panther Party. His personal charisma and his strong oratory skills complemented his organizational abilities, propelling him to national visibility at a young age.

The Mississippi Meredith March in 1966, after the shooting of James Meredith, marked the emergence of Carmichael as a national civil rights leader and the shift of that leadership to a new and younger generation. As Joseph suggests, it made him the most important black radical in America since Malcolm X. Equally important, that iconic march enabled him to take a place alongside Martin Luther King Jr. as a national black leader and spokesperson. On June 16, 1966, Carmichael changed the course and direction of the civil rights movement when he called on black people to start demanding “Black Power.”

That call divided Carmichael (and SNCC) from the mainstream civil rights groups and leaders, including King, who was uncomfortable with the Black Power slogan. Most white Americans were horrified by this militant turn. And more conservative black leaders like the Urban League’s Whitney Young and the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins denounced Carmichael, preferring compromise and accommodation with national commercial and political leaders to radical rhetoric and militant street action. Wilkins, absurdly, even characterized Black Power as racism in reverse, despite the strong evidence that Carmichael never embraced racial separatism (though there was some ambiguity about his attitude toward Jews) even during the height of his Black Power days.But one of the most intriguing features of “Stokely: A Life” involves the deep friendship between King and Carmichael that lasted until King’s tragic assassination in April 1968. King never repudiated Carmichael, despite his frequent unease with his younger political comrade. Indeed, the two men enjoyed each other’s company, and each had a powerful respect for the other. King never abandoned his commitment to nonviolent resistance, while Carmichael, like Nelson Mandela in South Africa, increasingly came to understand that all means necessary were required for authentic black liberation.

Later, King joined Carmichael in denouncing the Vietnam War. They were the key civil rights leaders who truly understood the linkages between domestic struggles against racism and the consummate evil of American military aggression in Southeast Asia. Both realized that America could not possibly address the historical inequities against African-Americans and other people of color while expending massive resources on an immoral war in Vietnam. Though ancillary to its primary focus, this book also reveals the deeper radicalism of King, a welcome contrast to the sanitized and superficial version of him that dominates American educational and media institutions. For all his gentleness, King was a committed opponent of racism and of the more fundamental American economic and social class disparities that pervaded Carmichael’s political vision for more than 30 years.

Joseph chronicles Carmichael’s multiple alliances and conflicts with various black leaders and groups. Among the most historically significant are his relationships with and separation from the Oakland-based Black Panther Party and figures such as Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver. His extensive international travels and numerous speaking appearances in the United States and abroad increased his notoriety and made him the target of government surveillance from the FBI and the CIA, and even potential prosecution. For a time, his passport was confiscated, eerily reminiscent of the McCarthy era of the 1950s, when Robeson and other radicals lost their right to travel. Like many of his militant predecessors, he felt the fury of a vindictive society intent on preserving white privilege and dominant economic power.

Perhaps least well known about Carmichael’s long political odyssey was his Pan-Africanism and his actual migration to the African continent. In 1968, he married noted South African singer Miriam Makeba and the couple left for Guinea in 1969. He became a mentee of exiled Ghanian President Kwame Nkrumah and an aide to Guinean President Sekou Toure. Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture, reflecting his dual African influences. Espousing a socialist, Pan-Africanist vision that became the chief focus for the remainder of his life, he continued his interest and occasional participation in American racial politics. He published his essays in a book titled “Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism,” a manifesto of his emerging political identity.

Joseph candidly analyzes the more problematic features of Carmichael’s later African-centered activities. He was, at best, insufficiently critical of the excesses of several African authoritarians and tyrants, including Idi Amin of Uganda, Moammar Gadhafi of Libya and Toure of Guinea itself. The record there was clear and unambiguous: Toure mistreated his political opponents harshly, even savagely, and Ture’s failure to acknowledge these realities, regardless of his delicate position in Guinea, constituted a serious moral failure. Joseph does a sound service to historical understanding in providing a nuanced but overall positive view of his biographical subject. Likewise, he acknowledges Carmichael’s personal failings in his two marriages, adding a useful human dimension to this broader political narrative.

“Stokely: A Life” is an outstanding addition to the burgeoning literature about the continuing African-American freedom struggle. Its most enduring contribution will likely be its restorative role in bringing Stokely Carmichael back into the arena of historical debate and public discourse. For much too long, the nation has relegated its militant black figures to the margins of the historical record. This book is a major antidote to that regrettable state of affairs.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.