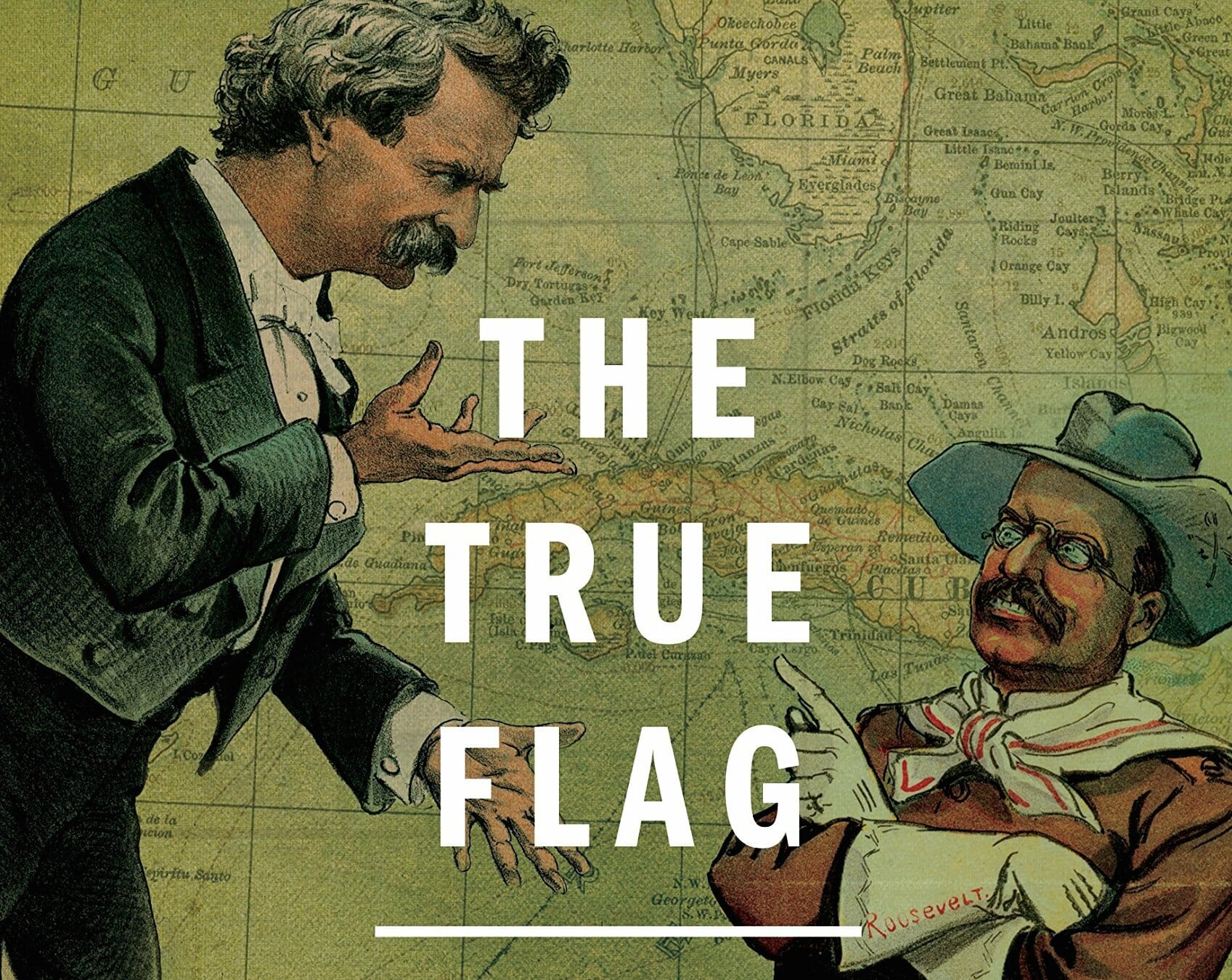

The Birth of American Empire

Stephen Kinzer's book illuminates the decisions of 1898-1902 that set the course of American wars and the overthrow of governments into the 21st century.

“The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire”

“The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire”

A book by Stephen Kinzer

By the final decade of the 19th century, the American project sanctified as Manifest Destiny was complete. The western boundary of the United States now stretched to the Pacific Ocean, leaving in its wake the genocide of Native Americans, the purchase of Louisiana without the consent of the governed, and a war of aggression against Mexico. What next? Pursue the colonialist mandate beyond continental borders—or not?

Stephen Kinzer’s “The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of the Empire” is a compact, bracing history of the answer to What next? It features the drama and decisions of four years—1898-1902—that, in Kinzer’s thesis, set the course of American wars, military expansion and the overthrow of governments throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, interrupted with brief, impermanent periods of “isolationism.”

Click here to read long excerpts from “The True Flag” at Google Books.

The author collates the eloquent rhetoric and caustic debates between expansionist members of Congress, including alpha male Theodore Roosevelt, aristocrat Henry Cabot Lodge, media giant William Randolph Hearst, and prominent anti-empire social critics and populist orators including Mark Twain, William Jennings Bryan and steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to capture vividly the divided political passions and high stakes of the day.

The empire builders used robust, positively coded terms like “the large policy” to label their aspirations for America’s pre-eminence among world powers and for the aggressive market ambitions of America’s capitalists. The anti-imperialists warned of the erosion of democracy at home, the rise of plutocracy and the blowback from military subordination of other peoples against their will, forecasting what, a century later, Chalmers Johnson incisively named the “sorrows of empire.”

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was the spark that inflamed the U.S. quest for overseas colonies. It began with Cuba and quickly stole Puerto Rico, then the Philippines, Guam (seized en route to the Philippines) and Hawaii—all in nine months. In public, expansionists framed these takeovers as beneficent: rescuing oppressed and backward people to catechize and civilize them.

Independence movements in Cuba, the Philippines and Hawaii were brutally suppressed. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed, particularly in the Philippines, which waged guerrilla warfare until its defeat in 1902. While American soldiers tortured and assassinated prisoners, burned villages and killed farm animals (a precursor to the later American War in Vietnam), a pliant press followed military orders and carried no unfavorable coverage.

The war in the Philippines was intensely terrorizing for women in particular. The Anti-Imperialist Review reported that “American soldiers had turned Manila into a world center of prostitution.” Amplifying this too-brief reference to the extreme toll of U.S. militarism on women, Janice Raymond writes in “Not a Choice, Not a Job,” that “U.S. prostitution colonialism, especially during the Philippine-American War, created the model for the U.S. military–prostitution complex in all parts of the world.” The system “assured U.S. soldiers certified sexual access to Filipinas and … became an intrinsic part of colonial practice in Cuba and Puerto Rico.”

Meanwhile, the empire seekers rubbed their covetous hands over the prospect of new customers for manufactured goods, and, in the case of the Philippines, a springboard to the Chinese and Japanese markets. Military bases in the Philippines and Guam would follow to protect and project U.S. economic and military power in East Asia.

Kinzer’s considerable talent joins meticulous research and engaging stories with a canine ability to sniff out the lies beneath the platitudes that sold the public on war. What he foregrounds so credibly are the oversize male egos of “large policy” politicians with more morally grounded and prescient anti-imperialist crusaders. Among these are Booker T. Washington, who, in speaking against U.S. imperialism abroad, warned that the cancer in our midst—racism, the legacy of slavery—will prove to be as dangerous to the country’s well-being as an attack from without. Many African-American anti-imperialist groups emerged and assailed U.S. imperialism for its intrinsic white racist arrogance.

With much detail and nuance, Kinzer tracks the fatal flaws of the immensely talented and populist orator William Jennings Bryan who, for his contrarian vote that sealed the doom of the Philippines, helped determine the fate of our country’s future as an empire. Likewise, the seemingly passive-aggressive William McKinley, elected in 1896 and again in 1900, is unmasked as the imperialist he grew to be over the course of his presidency.

The final chapter, “The Deep Hurt,” traces the arc of U.S. militarism across the 20th century and into the 21st—a long and unfinished arc that is neither moral nor bends toward justice. At each end of this ongoing arc, the words of two military veterans of U.S. foreign wars distill and corroborate Kinzer’s stateside exposé in “The True Flag.” Brig. Gen. Smedley Butler, born in 1881, began his career as a teenage Marine combat soldier assigned to Cuba and Puerto Rico during the U.S. invasion of those islands. He fought next in the U.S. war in the Philippines, ostensibly against Spanish imperialism but ultimately against the Philippine revolution for independence. Next he was assigned to fight against China during the Boxer Rebellion and was also stationed in Guam. He gained the highest rank and a host of medals during subsequent U.S. occupations and military interventions in Central America and the Caribbean, popularly known as the Banana Wars.

As Butler confessed in his iconoclastic book, “War Is a Racket,” he was “a bully boy for American corporations,” making countries safe for U.S. capitalism. More isolationist than anti-war, he nonetheless nailed the war profiteers—racketeers, in his unsparing lexicon—or the blood on their hands, as bracingly as any pacifist. War is the oldest, most profitable racket, he wrote—one in which billions of dollars are made for millions of lives destroyed.

Making the world “safe for democracy” was, at its core, making the world safe for war profits. Of diplomacy Butler wrote, “The State Department … is always talking about peace but thinking about war.” He proposed an “Amendment for Peace”: In essence, keep the military (Army, Navy, Air Force) on the continental U.S. for the purpose of defense against military invasions here.

And in the 21st century, Maj. Danny Sjursen, who served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan, proposes that the Department of Defense should be renamed the Department of Offense. His reasons: American troops are deployed in 70 percent of the world’s countries; American pilots are currently bombing seven countries; and the U.S., alone among nations, has divided the six inhabited continents into six military commands. Our military operations exceed U.S. national interests and are “unmoored” from reasoned strategy and our society’s needs, Sjursen concludes.

For all of this book’s strengths, one glaring lacuna is the minimalist presence of women in Kinzer’s depiction of the early anti-imperialist movement. “The True Flag” is premised on history as made by “great men”—good and bad. A “great woman” of this era, Jane Addams, elected vice-president of the Anti-Imperialist League after a brilliant speech, has only a bit part. Addams was renowned not only for her settlement house work at Hull House in Chicago, but also for speaking out unceasingly against imperialism and war. The FBI kept a file on her, and she was labeled among the most dangerous women in America. The author overlooked her influence in this era.

A second lacuna is omitting the original sins of imperial America: the genocide of Native Americans for their land, and the enslavement of Africans, which ultimately became the combustion engine of U.S. capitalism. Ironically, it was the pro-empire exhorters of 1898 who used the exploitative expansion within the early U.S. to defend extending Manifest Destiny to the Pacific region. “If we should not do this in the Philippines, why was it acceptable to do here?” challenged Henry Cabot Lodge, the imperialist senator from Massachusetts.

The Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran could have penned these words from 1933 for our national dilemma today: Pity the nation that acclaims the bully as hero and that deems the glittering conqueror bountiful. …

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.