The Fall of Mosul and the False Promises of Modern History

The fall of Mosul to the radical, extremist Islamic State of Iraq and Syria is a set of historical indictments.

A girl stands outside her house in the District of Mosul, Iraq, as soldiers carry out an operation behind her. DVIDSHUB (CC BY 2.0)

This post originally ran on Juan Cole’s Web page.

The fall of Mosul to the radical, extremist Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is a set of historical indictments. Mosul is Iraq’s second largest city, population roughly 2 million (think Houston) until today, when much of the population was fleeing. While this would-be al-Qaeda affiliate took part of Falluja and Ramadi last winter, those are smaller, less consequential places and in Falluja tribal elders persuaded the prime minister not to commit the national army to reducing the city.

It is an indictment of the George W. Bush administration, which falsely said it was going into Iraq because of a connection between al-Qaeda and Baghdad. There was none. Ironically, by invading, occupying, weakening and looting Iraq, Bush and Cheney brought al-Qaeda into the country and so weakened it as to allow it actually to take and hold territory in our own time. They put nothing in place of the system they tore down. They destroyed the socialist economy without succeeding in building private firms or commerce. They put in place an electoral system that emphasizes religious and ethnic divisions. They helped provoke a civil war in 2006-2007, and took credit for its subsiding in 2007-2008, attributing it to a troop escalation of 30,000 men (not very plausible). In fact, the Shiite militias won the civil war on the ground, turning Baghdad into a largely Shiite city and expelling many Sunnis to places like Mosul. There are resentments.

Those who will say that the U.S. should have left troops in Iraq do not say how that could have happened. The Iraqi parliament voted against it. There was never any prospect in 2011 of the vote going any other way. Because the U.S. occupation of Iraq was horrible for Iraqis and they resented it. Should the Obama administration have reinvaded and treated the Iraqi parliament the way Gen. Bonaparte treated the French one?

I hasten to say that the difficulty Baghdad is having with keeping Mosul is also an indictment of the Saddam Hussein regime (1979-2003), which pioneered the tactic of sectarian rule, basing itself on a Sunni-heavy Baath Party in the center-north and largely neglecting or excluding the Shiite South. Now the Shiites have reversed that strategy, creating a Baghdad-Najaf-Basra base.

Mosul’s changed circumstances is also an indictment of the irresponsible use to which Sunni fundamentalists in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the Oil Gulf are putting their riches. The high petroleum prices, usually over $100 a barrel, of the past few years in a row, have injected trillions of dollars into the Gulf. Some of that money has sloshed into the hands of people who rather admired Usama B. Laden and who are perfectly willing to fund his clones to take over major cities like Aleppo and Mosul. The vaunted U.S. Treasury Department ability to stop money transfers by people whom Washington does not like has faltered in this case. Is it because Washington is de facto allied with the billionaire Salafis of Kuwait City in Syria, where both want to see the Bashar al-Assad government overthrown and Iran weakened? The descent of the U.S. into deep debt, and the emergence of Gulf states and sovereign wealth funds is a tremendous shift of geopolitical power to Riyadh, Kuwait City and Abu Dhabi, who can now simply buy Egyptian domestic and foreign policy away from Washington. They are also trying to buy a Salafi State of Syria and a Salafi state of northern and western Iraq.

The fall of Mosul is an indictment of the new Iraqi army, which is well equipped and some of its troops well trained , and which seems to have just run away from the ISIS fighters, allowing some heavy weapons to fall into their hands.

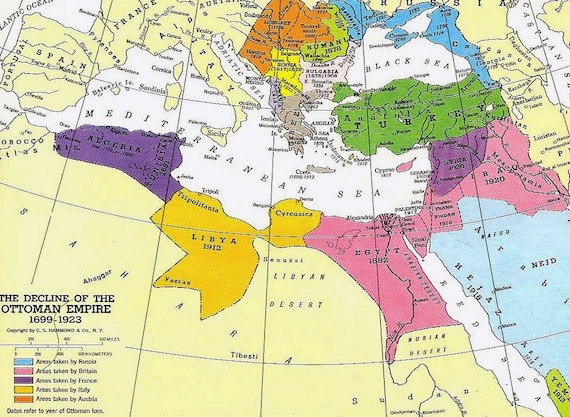

It is an indictment of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and of the Shiite political elite that took over Iraq from 2005, and which has never been interested in reconciliation with the Sunni Arabs. It is not merely a sectarian issue. The particular Shiite parties that have consistently won elections are those of the religious right among Shiites. Before the CIA cooperated with the Baath Party to destroy the Iraqi Left, many Shiites were secular and the Iraqi Communist Party united them with many of the country’s Jews back in the 1950s. The Shiite religious parties dream of a Shiite state. Many want to implement a fundamentalist vision of Islamic law. There is little place for Sunni Kurds or Sunni Arabs in such a state. Al-Maliki himself seems to have a problem with the Sunnis, and his inability to integrate them into his government means that he is losing them to Sunni radicals. His inability to reach out to Sunni Arabs made plausible what the entire Iraqi parliament rejected when it came out, the Biden plan for the partition of the country. Usama Nujaifi, parliamentarian from Mosul and speaker of the Iraqi parliament, was driven to say a few years ago that for the first time since WW I, the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement (envisioning a French Syria and British Iraq) was up for renegotiation.

It is also an indictment of the shameful European imperial scramble for the Middle East during and after WW I and the failed barracuda colonialism of the interwar period, as London and Paris sought oil and other resources, and strategic advantage, in areas they had promised the League of Nations they would prepare for independence. In one instance, they just gave away Ottoman Palestine to a European population, leading to 12 million stateless and displaced people to this day.

During WW I, British diplomats promised lots of people lots of things, and were not embarrassed to double book. The foreign office promised France Syria but the Arab Bureau in Cairo promised Syria to Sharif Hussein of Mecca. Cairo wanted Iraq for Sharif Hussein, but so did New Delhi (the British Government of India couldn’t see the difference between ruling Iraq and ruling Sindh or Rajasthan).

As the war was winding down it was clear that the Ottoman Empire would collapse. The French saw Mosul, with its oil wealth, as part of Syria. The British in New Delhi and in Cairo, for all their wrangling, agreed that it should be part of Iraq, which British and British Indian troops were conquering.

When British Prime Minister Lloyd George met with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau at Versailles, he was eager to push back French claims on Mosul. Since the British and their Arab allies had taken Damascus from the Ottomans, some wanted to renege on the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 altogether. President Woodrow Wilson was also there, with his ideas of self-determination for the peoples of the former empires, and he didn’t want to just see an imperial grab for them. Clemenceau is said to have remarked that he felt he was caught between Jesus Christ and Napoleon.

When Lloyd George met with Clemenceau, the latter is said to have asked him, “What do you want?” Lloyd George said, “Mosul.” Clemenceau agreed. Anything else? “Jerusalem.” You shall have it. In return, the French were assured of Syria, which meant that Lloyd George had betrayed Sharif Hussein and his son Faisal b. Hussein, then in Damascus, for the sake of Mosul’s oil. Afterwards it is said that Lloyd George felt he had gained these boons from Clemenceau so easily that he should have asked for more.

Integrating Mosul into British Iraq, over which London placed Faisal b. Hussein as imported king after the French unceremoniously ushered him from Damascus, allowed the British to depend on the old Ottoman Sunni elite, including former Ottoman officers trained in what is now Turkey. This strategy marginalized the Shiite south, full of poor peasants and small towns, which, if they gave the British trouble, were simply bombed by the RAF. (Iraq under British rule was intensively aerially bombed for a decade and RAF officers were so embarrassed by these proceedings that they worried about the British public finding out.)

To rule fractious Syria, the French (1920-1943) appealed to religious minorities such as the Alawites and Christians to divide and rule; Alawite peasants were willing to join the colonial military as proud Damascene Sunni families largely were not, but when the age of military dictatorships overtook the postcolonial Middle east, the Alawites were in a good position to take over Syria, which they definitively did in 1970.

The countries now known as Syria and Iraq came into modernity having been for 400 years part of the Ottoman Empire. Sometimes it ruled what is now Iraq as a single province with roughly its modern borders, sometimes it ruled it as a set of smaller provinces. At some points the city of Mosul was the seat of a province of the same name. More often its top official reported to the Sultan in Istanbul through Baghdad. Mosul, a large urban center on the caravan and river trade routes stretching to Aleppo and Tripoli to the west and to Basra and India to the southeast, was a major urban place. It was very different from southern Iraq, which through the 19th century converted to Shiite Islam (in part under Indian Shiite influence) and was less urban and more tribal. Still, it was united with the south by trade along the Tigris and by the structures of Ottoman rule.

PM Nouri al-Maliki can only get Iraq back by allying with nationalist Sunnis in the north. Otherwise, for him simply brutally to occupy the city with Shiite troops and artillery and aerial bombing will make him look like his neighbor, Bashar al-Assad.

——

Related video:

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.