The ‘Highest Danger’ of the Cold War Isn’t Behind Us

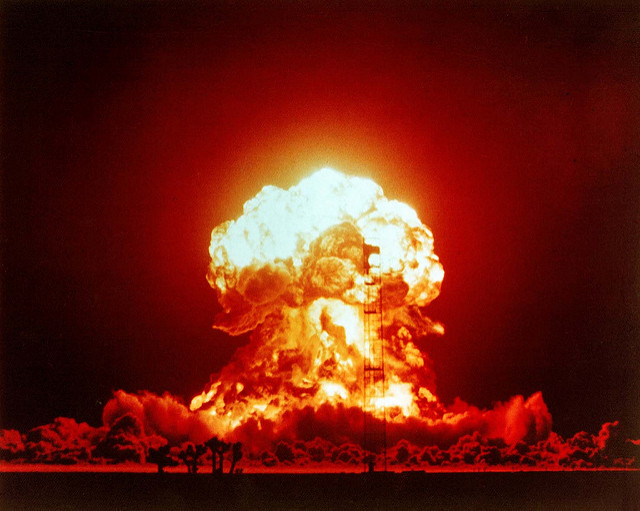

"The Kremlinologist" authors Jenny and Sherry Thompson discuss their landmark book, Soviet communism and the real dangers of nuclear war. International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons / Flickr.

International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons / Flickr.

Listen in on their discussion to find out what that central misconception is, to hear the Thompsons’ take on whether communism is best seen as a nationalist or an internationalist phenomenon, and why they think the current moment is closer to the most dangerous point in the Cold War than many Americans realize. You can also read a transcript of the interview below:

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence. And I’ve got a remarkable book we’re going to talk about today. It’s called The Kremlinologist. It’s the story of maybe one of the most admirable figures we’ve had in the foreign service agency of the State Department, and foreign service officer, a man named Llewellyn E. Thompson. At one point he was our ambassador in Moscow, the most critical point in the history of the Cold War, threatened with nuclear disaster and everything else. And the thing that made me suspicious of this book at first, it happens to be written by his daughters, who also were there, Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson. And my first response was, OK, they’re going to have very nice things to say about their father. And, boy, was I wrong. This is the indispensable book to understanding the trajectory of the Cold War: what was it really all about? And in particular, about a fundamental fallacy in the Cold War. So let me bring you two in, Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson. We’re doing this by phone. But what you did–and I know from your introduction and so forth–you spent at least 13 years on this; you had access to your father’s papers; he wasn’t a person to write a lot about what he was doing. And you’ve come up with maybe the clearest insight into what I would consider to be the essential folly of the Cold War. That we could be virtuous at the same time as we were conniving. Can you comment on that, or bring us into how you came to write the book?

Sherry Thompson: Sure. This is Sherry. We really started this whole project for our families. Because our father died quite young, so we wanted to discover who he was, and what his career was about, and we wanted to share that with our families. And it wasn’t until we actually started interviewing people that we realized it really needed to be a proper book. And I think that’s how it became as much a history of the Cold War, with his life as a thread running through it.

Jenny Thompson: This is Jenny. We also had to meet in Washington and go to the archives, and do the research there. And when we started, we didn’t really think about footnotes and references, and then we realized–especially since we were his daughters–that we had to back up everything we said with some sort of citation or reference. So that’s another reason it took so long, and also because we were both working and raising families, and–not much time.

RS: And let me just say at the outset, this book is being honored by professionals in this field, the American Academy of Diplomacy. And they generally honor an exemplary member of their own tribe, and you’re being honored days after we do this interview here in mid-November, in Washington. And again, I want to repeat–I’m not saying this in just an off-handed way. You know, I read this book right through, and I am enormously impressed with it. And what I’m impressed with–not that it gives us a great insight into your father, and you really did a first-rate job of journalism, is what this book is. It almost confuses it to mention that you’re talking about your father, because you’re actually quite objective about his limitations, his strengths, his–you know, as a human being. So, did you get a great deal of access and support in writing this?

JT: Not really. Not–I mean, we interviewed his colleagues, obviously, and we interviewed the people that worked with him. Chip Bohlen has passed away, but he wrote a book that we used, also. But we had the interviews, but nobody actually helped us to write the book or organize it.

RS: Well, OK, then–

ST: What we did have help with was, after we finished the draft, we sent chapters out to various people, including Chip Bohlen’s daughter, to read what we had written, to make sure that we weren’t saying something too outlandish.

RS: Well, I don’t think you say anything outlandish. But you do say things that are quite provocative. And it seems to me the basic issue raised by your father was that the whole construction of the Cold War was built on a fallacy. I don’t know that he would use that word, because he was witnessing it as it evolved. But was communism nationalist or internationalist? And speaking primarily about its fountainhead, the Soviet Union. And the assumption of the Cold War was there was this ideology of communism; the Soviet Union had adopted it, and this led inevitably to a universalist, expansionist position. But as the book moves along, we find that the Soviet Union was largely a nationalist phenomenon, and that inevitably got into conflict, first with Tito in Yugoslavia, another communist, but he had fought his own war against the Germans; and then of course the Sino-Soviet dispute. But then even when you get up to the Vietnam War, clearly the Vietnamese communists were Vietnamese first, and nationalists. And I think your father–and he says it in his writings and so forth–felt this was the great era we were making, that we underestimated the nationalist component. Is that not one of the important messages of your book?

ST: Yes, I think it is. I think that there was always this tension between the nationalist impulse and the internationalist impulse, if you will. And our father was very–well, he argued very strongly in favor of looking at our policies to make sure that we would encourage the more nationalist view. And of course nationalist has lots of connotations right now, but the nationalist view which was more benign than the ideological communist view, yeah.

JT: I would add that he was also very much aware of the tension between the Soviet Union and China. China was a much more revolutionary sort of communist country, and they were very much for exporting communism, often criticized the Soviet Union for not doing enough on the, you know, pushing it internationally. And this was the sort of tension between them, and our father also would advise that we had to do everything possible to encourage the Soviet Union to not go the Chinese way.

RS: Well, and let’s stick on that point, because it’s the key era of the last 50 years; maybe it’s an era we’re making now in our appraisal of Russia without communism. We have a hard time understanding anyone else’s nationalism. You have, even China–and there your father probably was incorrect, I think–the idea that somehow they were so slavishly involved with Marxist, Leninism, ideology and so forth; well, no. The main reason that they were hostile to Russia, they used that argument, but it turned out in fact they have Chinese nationalists. And one of the ironies of the whole Cold War history, as we fight this long war in Vietnam against Vietnamese communism, not because we think the Vietnamese have an army or a navy that can hurt us, but because we think they’re an extension of Chinese communist and Russian communist power. And we lose the most ignominious defeat that we’ve ever had in Vietnam. And what happens? Instead of the Vietnamese communists attacking San Diego, the Chinese and the Vietnamese communists go to war. They are fighting over their border, and they’re still fighting over islands that they both claim. So even in the case, or maybe particularly in the case of China, this argument your father was advancing, that nationalism in some sense supersedes communism or ideology, really was the important correction, and that the U.S. government did not heed, at least at the highest level.

JT: Yeah, I would say that you’re right. And I think, as you mentioned, Russia today, I think people don’t really realize that Russia today is not the Soviet Union. It doesn’t profess an ideology. Obviously it has nationalist interests. And because of the sort of Cold War mindset, it’s easy to whip up anti-Russian sentiment, simply because we’re ready to accept that. We were accepting, you know, we were anti-Soviet during the Cold War. I think what we need to do now is be very careful, because we’re getting into a position of another arms race with Russia today, and also the possibility of rising rhetoric and making the tensions higher will, could possibly lead to even nuclear war. And we’re kind of in the same position we were in at the highest danger of the Cold War.

RS: I think that’s an important observation, and it’s one your father would, I think, be making now. Because there was a wing of the State Department that certainly was naive, and even apologetic, about the Soviet Union. That was not your father; he was tough-minded, independent, saw the failings quite clearly. But the key operative thing–and this is, amazingly enough, it was Richard Nixon who kind of embraced this, both for Russia and China–we could do business with them. We could live with them, if we understood their nationalism. And where we got into trouble, I think, in the mind of your father, was when people like Paul Nitze, and the neocons later, and everything, put their ideology and then assumed the other side’s ideology, and boom, we’re off to, on the road to World War III. And your father’s wisdom was, you know–and reinforced as he learned more and more, and rose higher and higher in the government; he got to be quite high under Lyndon Johnson, knew a lot about the covert operations and everything. And he came to two conclusions. One–and this was a very important observation in your book, I think–he understood about the Soviet Union, that there was an enormous contradiction between their appearance, their illusions, what they presented themselves as, and what they really were. And it’s by the end of your book, when you’re discussing Vietnam and covert operations–your father comes to this really depressing conclusion that, you know what, we do the same thing. Again, I don’t want to put my own interpretation here, but it was quite clear at the end of the book that he was shocked that there’s that same kind of genre of deception, self-deception, on the part of the elites of both of these societies.

ST: Well, I think that he did have some disillusion when he became part of the 303 Committee, which is the covert operations, committee that oversaw, OK’d covert operations. And so he was [in] a much larger role than when he was just dealing specifically with Soviet affairs. But it also, it’s a speculation on our part, but he complained a lot about having to do that job. And I think that part of that was because of that. And he saw his role as constantly being the guy in the middle who was trying to explain the Soviets to the Americans, and the Americans to the Soviets.

RS: But not just that. I mean, he–he–look, there’s a subtext in your book. There are these foreign service officers, like your father, Llewellyn Thompson, a defender of historical accuracy, of scholarship, getting it right, and respecting other people’s history. And that is not the dominant, or it’s not the ever-present, caution in the pursuit of foreign policy, to put it mildly. And I think that was the struggle he was having. And when the Lyndon Johnson administration, when they said look, let’s put this guy in with the–tell us about the 303 Committee, and how it developed, and what it was doing. And he was really cautioning against the dangers of that approach.

JT: The 303 Committee was a committee in the State Department that was supposed to oversee CIA operations, so the CIA would have some oversight. All the things in the 303 Committee are still top-secret; it’s impossible to get ahold of them. Some of this came out during the Church investigations, but it’s still impossible to know exactly what they discussed in, you know, in all of those meetings. One of the things that we learned in doing this biography was the necessity to have empathy for the other. And I think this is, this is a major lesson that we learned from the book: you have to try to understand the other, and to anticipate what the consequences might be of any particular action that you contemplate. Long-term consequences are really overlooked these days; everybody goes for the short-term gain, and they don’t look at the long, long picture. And this is one of the things that Thompson did quite well; he would always look at where this would lead, and therefore, his advice was based on that.

RS: Your father was–understood bad things happen, and there are bad people. He was quite aggressive in confronting them; he was quite brave. He’s the one who stayed in Moscow when the rest of the embassy and everybody else went off to safer quarters. He’s a guy who went through the war, saw the horror; he also saw the horror of Stalinism and, you know, the torture of people and so forth. So this is a tough cookie, your father. On the other hand he said, wait a minute, let’s not get such a superiority complex here that we are the center of virtue and these people have no claim on anything. I mean, that was really his wisdom. We had others like him, but he might be the person, if we had listened to–it wasn’t just we would have had a more sensible policy towards the Soviet Union; we would probably not have gone into Vietnam. We would not have overthrown Mossadegh in Iran; we would not have done a lot of the serious mischief we’ve done in the world, because he knew that derring-do, undercover stuff had consequence.

JT: Well, yes, I think that’s true. And the other thing that he felt was really important is that you should not isolate countries; you should not isolate, you know, he was against isolating the Soviet Union, he was. Because he thought, as long as you’re talking, if you’re talking to the other side and you can talk to the other side–we talked to Stalin, we talked to Khrushchev, we talked to anybody–as long as you keep talking, then there’s a possibility to avoid misunderstanding. It’s when you don’t talk to the other person you start imagining things, and then it could lead to very detrimental action. So he was very much for talking. I think because of talking to the Soviets, we did avoid, you know, a lot of dangerous possibilities.

RS: Well, the most dangerous, we probably would have blown the world up over the Cuban missile crisis. And you have a compelling description of that whole encounter. But let’s take it to the present, because this book is not–OK, history is important; this book is a cautionary tale for how we proceed from this moment on. And the interesting thing is, you in your book, without apologizing–there’s nothing apologetic, you’re quite severe in your condemnation of Stalin and his oppression of the Polish people, his oppression of his own people, his oppression even of idealistic people who took refuge in the Soviet Union. And you have a nuanced and complex view of Khrushchev. I should point out to people listening to this, you were there. You were up close to these people. You saw how they interacted. You were part of the American embassy, and your mother was sort of a major figure in encountering the Russian people, from the top down. So there’s nothing myopic about your book; it’s hard-boiled. And yet–and yet, talking to the other people, the other–understanding the other–is the great takeaway from this book. And I want to bring it to the present, because you know, Khrushchev was a member of the Communist Party. He was given to the ideology; you now have in Vladimir Putin, in Russia, someone who has soundly rejected all that; he defeated the Communist Party candidates in elections, he is the guy who has embraced the Russian Orthodox Church. So if you take us to Russia now, your father tried to understand Stalin and Khrushchev and others in Russia; he was our ambassador, Llewellyn Thompson. And that paid off big dividends, in terms of understanding and agreements and controlling nuclear weapons. Now we have a guy, we have red-baiting and we don’t have a red there. And maybe, you know, you can draw upon your own Russian experience to assess the current moment.

ST: Well, I would like to just back up a little bit to Stalin and Khrushchev and say that because he had this ability to empathize and understand, or try to, that he recognized the shift from Stalin to Khrushchev, and how it was different. And there’s a point in the book that he’s talking to John Foster Dulles, who was the Secretary of State at the time, and he’s trying to explain to him that it’s not the same. And it’s not the same now, either. And we’re certainly not experts in contemporary Russia, but I would just caution that we not sort of fall back on a stereotype of what we think the Russians are, in terms of what they were during the Soviet period.

RS: I think that’s an important observation. It’s not one that’s really stated in the book, but I think that you come away from this book thinking, wait a minute, are we–are we even doing it in a more insane way now? And one criticism I had, by the way, of the book, I couldn’t understand–it’s a minor criticism–you kept referring to the Soviets, not the Russians, in World War II, and their sacrifice, and what they went through. And yet you don’t refer to the Germans as the Nazis.

JT: They were Germans. And the problem of maybe using that word, Nazi, it tries to make it seem like they were, you know, very monstrous. Which they were–but they were also Germans. Calling them Soviets and Russians, I think it’s important, because today people confuse it. You know, they confuse Russians with Soviets. They were–there was the Soviet Union, and now there is Russia, and it’s not the same thing. And I think a lot of this whipping-up of anti-Russian sentiment in the United States may be really due to domestic politics. Since our President Trump said he’s going to try to talk to the Russians, then you know, the other side decides, well, the Russians have to be bad, because Trump wants to talk to them. I think that’s a mistake; I think Thompson would certainly advise today that it’s necessary to talk to the Russians. And not just Trump and Putin, because OK, they’re the leaders of the two countries; we need to have communication on all lower levels. When Thompson was ambassador, he encouraged all sorts of cultural exchanges, scientific exchanges, because you have to have these people talking to each other, understanding each other. So as Sherry said, we don’t fall into the error of making some sort of stereotype that makes it easy to hate.

RS: Yeah–I understand the Germans were not all Nazis, and you can be a Nazi without being a German, you can be a communist without being a Russian. But the interesting thing is, our government, the U.S. government, despite Nuremberg, recruited a lot of these Germans into our own, new national security state. Had no trouble with it. So it’s a question of demonization. On the other hand, with the Russians, who were our allies, there was almost no slack given to them. And in your book, you recount the suffering–by the way, the book is a really intelligent analysis, offers an intelligent analysis, and really thorough, of the wartime agreements, Yalta and Potsdam and so forth, and Tehran and the Cairo–all of that discussion. You know, Thompson was critical to it; he was there, your father, and you’ve got the documents. And one of the interesting things that comes from it is that, basically, Russia had turned the tide of the war before the United States entered. They had paid the heaviest price of any nation. They had suffered enormously, and then there’s the critical moment in which–and this is before the Normandy landing–that the tide is turned, and the Germans are now in retreat. So the U.S. only opens the second front after the Russians have, in effect, won the war. And yet there’s a resistance on the part of England, more so than the United States, Churchill more than FDR, of accepting that. And that’s a part of this history that really is hardly ever mentioned. It’s well-known in Russia, but it’s not well-known in our own country.

ST: No, that’s true, it’s one of the things that when we talked about having to self-educate, these things that we didn’t really fully understand came forward for us. And that was certainly one of the most emotional ones, just how much that country suffered. It enables you to have some empathy for their attitude later, because they were not given credit for it.

RS: Well, that’s an enormous gap. I mean, when we try to understand Putin, we try to understand, you know, why this guy has some considerable popularity in his own country. He represents a nationalism–he doesn’t represent communism. Let me cut to the chase here of what I think is a discussion that your book provokes. There’s a struggle within your own book, because you respect your father; you respect your country; you respect our history, our commitment to freedom and so forth and so on. But there’s an idea tagging at this, at least in my mind–wait a minute. Are we so virtuous? And it starts for me in the beginning of your book, and then at one scene you have, I forget his name, but one of the American diplomats–I think it was Henderson, I’m not sure–giving out an Indian war cry at some thing. [Laughs] I don’t know what he did. And I thought, wait a minute. Your father, and your family, was part of this westward migration, which really was the start of empire and the total disregard of the Native American population. And then in fact, if we look at our history, it has been one of expansion, not just within our own claimed territory of North America. And what I see in your book is maybe your father was the best of the best and the brightest, but he still operated within that idea that we were the chosen, most advanced, most enlightened civilization the world had ever seen. That confidence, that, if not arrogance, that confidence, allows one to put up with a lot of bad stuff. And like Vietnam, where we dropped more bombs on the people of Indochina than we did in World War II. And you actually have a thing in there where you talk about, there were people who wanted to bomb them back to the Stone Age. Imagine, the best and the brightest, and there’s some of them are talking about bombing another people back to the Stone Age–for what, fighting against colonialism, having their own idea of their nationalism? And I think your father was torn between a commitment and a belief that America was the city on the hill, the best of societies–to use Ronald Reagan’s idea–and yet, maybe he saw too much that went against that narrative.

ST: Well, certainly, I think you’re right. He was a believer; he believed in his country, he was patriotic from that perspective. But everybody’s life, you go through an awakening. And I think that he did, too. And I’d also like to point out that sort of the opposite coin, or the hand-in-hand, with empathy is the ability to look at yourself more clearly. And I think that developed as he became exposed to what his country was doing. And I would also like to point out that one thing that he did believe in, and talked about a lot in many of his speeches–we’ve read it over and over again in his papers–was that he truly believed that we believed in self-determination. And that’s one of the things that I think bothered him most about Vietnam, was that he really thought that we believed in self-determination, and that we were for it for other people. So that whole colonial tension was difficult for him, I think.

JT: Yes, and I would also add that he obviously lived under the Soviet system; he saw the Soviet system, he lived in Europe, saw different kinds of systems there. And I think what his conclusion was, that democracy–OK, even if it’s as they say, messy and doesn’t work always quite right–it’s the best system to permit the individual to have as much freedom as possible, or at least in the, you know, I don’t know now, but before. And this is what he thought was important, and he thought the best counterpoint for, let’s say, countries being attracted to communism or the Soviet system, was to make our system work as best as possible. To be a showcase, to show what we could do, and then people would be able to choose, and they would choose the way we had our government, because they would see that it was the best one. I think we kind of forgot about that. We need to concentrate a lot more in making our country better.

ST: Live up to its ideals, as opposed to trying to impose a structure on somebody else.

JT: Exactly.

RS: But let me push this a little bit. I think your father–and there are things that he wrote about maybe other people finding their own way. And if you take China or Vietnam, for example, the assumption–and, or Russia, for that matter, where communism is now basically dead, and in China and Vietnam it’s a fundamentally different thing; it’s actually a new form of capitalism. I think your father had the idea that along with these being basically nationalist phenomena, they would find their own way, and that maybe our way was not the only way. He wrote that. It’s in your book. That maybe, you know, maybe the Chinese people will get this sorted out, without our interference, better. Maybe the Vietnamese will figure it out better. Because after all, we lost the war in Vietnam, and we never were able to overthrow the communist government in China, which we intended to do, and acted on quite aggressively. And still they’ve gone through enormous changes. Remember, he was there when we were arguing about whether China should be allowed to be in the UN. You know, communist China. And the inevitability of war with China–it’s still communist China, it’s still communist Vietnam, and they’re our great trading partners, right?

JT: Ah, he did believe, as I mentioned before, that you had to have a communication with these people, not impose your system on them. You have to communicate with them, talk to them. And there are obviously areas where we’re going to be able to work together and coincide. You know, we should be working now with the Chinese and the Russians to lower this arms race, and the danger of starting a nuclear war.

RS: And it’s interesting, in your book you mention, with all the wartime agreements and discussion and all the assumptions, something very big happened: the creation and the dropping of the atomic bomb. That’s a pivotal moment in your analysis in the book. That for all those wartime agreements, the talk about a UN, suddenly something huge had happened. That shocked the whole relationship. And now, we’re kind of indifferent to the existence of these weapons. So maybe the way to conclude this, you people lived in the old Soviet Union, you’ve thought a lot about Russia, you’ve just written a terrific book, The Kremlinologist: Llewellyn E Thompson, America’s Man in [Cold War Moscow]. And you were the offspring of somebody who probably understood this phenomenon best. How do you look at the current situation, with Russia still having half of the world’s nuclear weapons, in effect, and where do you think we are now, and what should we do about it?

ST: Well, we’re both very happy you asked that question, because we think it’s the most important thing that we need to worry about at the moment. And we have kind of forgotten; we’ve gotten complacent about nuclear weapons. And it doesn’t take a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia to do us all in; it could even be a small regional exchange between Pakistan and India, for instance. And the weapons that we have now are so much more powerful and so much more dangerous, and now that we have good climate modeling, we understand that even an exchange, a regional exchange, could be enough to virtually destroy the planet.

JT: I just wanted to add another thing, that now, according to Putin, he’s developed supersonic missiles that could arrive to the United States in virtually seconds, and we’re developing them, too. So there’s another element why we have to bring down this arms race, is that there won’t be time. There won’t be time to think, what are we really doing? There won’t be time to backtrack. One of the things that saved us in the Cuban Missile Crisis was that there was time. They had about a week to think about what they were going to do. But the way we’re developing the weapons now, and we’re even thinking of putting computers in charge of firing these things, it’s extremely dangerous. And we’re not talking about that danger anymore, as Sherry said.

RS: As people who basically grew up in the old Soviet Union, and are conversant with the society, thinking about your father now, what would be his observation of where we are compared to where we were?

JT: Well, I think he would be shocked. I think we would be shocked at how little we have progressed. One of the things he once said in a speech he made in Austria was he said, you know, we’ve come so far in research and science and culture, but we have not advanced, really, much as human beings, or in understanding each other. So I think he would be dismayed that despite all the progress we’ve made, we really haven’t moved very far.

ST: Well, I would just like to say again, that same speech that he gave in Vienna–this is much, a long time after he served in Vienna. And what he foresaw was that we were not looking far enough down the road, that we were developing technologies without any concern for what it would do to labor, for instance. And he made the observation that he thought that the conflicts of the future were not going to necessarily be East and West, but would be North and South, because we were not helping these people rise up in their economics and so forth. And that this was a mistake, that we were exploiting the post-colonial countries instead of helping them.

RS: The book is The Kremlinologist. The authors of this book, despite being his daughters, have done an incredibly objective, profound, and let me say studious study of not just their father, but rather, really, the whole trajectory of the Cold War. That’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. Our producers are Isabel Carreon and Joshua Scheer. The engineering is supplied by Mario Diaz and Kat Yore at KCRW, and Victor Figueroa here at the USC School, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. And we thank USC for making these facilities available to us. See you next week.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.