‘The Lovers and the Despot’ Film Review: The Curious Case of Kim Jong Il’s Stolen Filmmakers

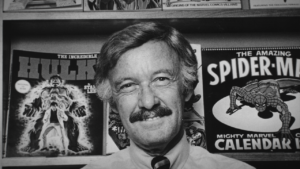

Not even North Korea's late supreme leader was immune to Hollywood’s charms. (Pictured, Choi Eun Hee, left, and Shin Sang Ok.)

Actress Choi Eun Hee, left, and producer-director Shin Sang Ok in “The Lovers and the Despot.” (Magnolia Pictures)

As countless Beyoncé fans in other countries can attest, cultural exportation is an especially persuasive method of flexing soft power on the global stage. It’s not exactly a state secret that pop cultural products carry with them the stamp of the society, as well as the individual artist and industry, that produced them — or that the U.S. has been the world’s top pusher for over a century.

That point clearly wasn’t lost on North Korea’s Kim Jong Il. Long before that government’s innermost sanctum was penetrated by American cultural ambassador Dennis Rodman, and before James Franco and Seth Rogen mocked diplomacy with “The Interview,” the late ruler and father of current leader Kim Jong Un grew up in opulent isolation. Under the long shadow of his own father, the revolutionary Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il fancied himself an artiste while surrounded by throngs of handlers ready to indulge his every delusion. At least that’s how he’s pictured by writer-directors Ross Adam and Robert Cannan in “The Lovers and the Despot,” a story so bizarre it would make for a solid fictional film if it weren’t already a remarkable documentary.

And despite his blistering disdain for practically everything about the West, not to mention for the enemy territory just to the south, even his own peculiar boy-in-a-bubble upbringing couldn’t make Kim immune to Hollywood’s charms. The power of celebrity has some serious reach, as the years since have only made more strikingly apparent — but that comes later. Back in the ’70s, as shown in Adam and Cannan’s priceless archival footage and more contemporary testimonials, the future Supreme Leader badly wanted his name in lights.

But how’s a hermetically sealed, starry-eyed dictator supposed to chase his silver-screen dreams in an international film scene thoroughly owned by foreign players? After discovering, as many a studio chief had before him, that good talent is so hard to come by, Kim went old-school strongman and decided to just steal a couple from someone else’s pool.

And we’re not talking about cultural appropriation here; in 1978, he sent his henchmen across enemy lines and detained an actual couple. A couple of exes, actually. Until a beat or two before then, producer-director Shin Sang Ok and actress Choi Eun Hee had been a real item and a really big deal in South Korea. By the time they were taken, the “Prince of Korean Cinema” and his onetime leading lady were divorced and struggling with two adopted kids and pitiless creditors.

Choi thought she was meeting a legitimate business prospect in Hong Kong and wound up on a one-way boat trip to Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital. But a trail of personal effects including one of Shin’s movie scripts that was a bit too apropos tipped off investigators that she might have defected, however unwillingly, to Kim’s domain. Shin traced her steps in Hong Kong in an attempt to find her before he, too, was seized. Their reunion in North Korea happened half a decade later, once Shin had done hard time in a prison camp as part of a brutal indoctrination sequence that Kim, in typical bureaucratic style, later blamed on his underlings.

Thus ensued what may be the strangest tale of rekindled romance and artistic slavery in movie history. With Choi’s help, Shin began their joint production of 17 films, made in just over two years and under the watch of the world’s most heavy-handed executive producer, by shooting North Korea’s first love story on film, just as circumstances conspired to bring them back together. That’s only one of several details from the documentary that might seem like gimmicky flourishes if the couple’s second act hadn’t gone down as it did.

It’s also one of many moments in the narrative when the already hazy distinctions between cinematic fantasy and reality (as in actual events, not “unscripted” entertainment) collapse. In a line that could serve as the only pull-quote necessary for promotional materials, one character observes: “When put in extreme situations, people imitate what they see in movies.” In another, Choi tells of how she experienced a particularly fateful moment as though she were acting out a scene.

Details about what eventually became of the kidnapped pair can be easily Googled. But by this point, it’s hardly a spoiler to say that what Shin and Choi, as well as Kim, wanted most was their own Hollywood ending. And in a way, all but one of them got it.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.