The Near Future Could Be Hotter Than Anyone Expected

Climate scientists are haunted by a global temperature rise 56 million years ago, which could mean much more heat very soon. Shutterstock

Shutterstock

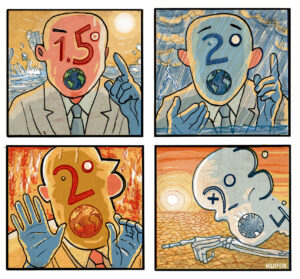

We could in the near future be experiencing much more heat than we now expect. As carbon dioxide levels rise, global warming could accelerate, rather than merely keep pace with the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

This is a lesson to be drawn from new computer simulations of the conditions that must have precipitated a dramatic shift in global climate 56 million years ago, when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rose at least 1000 parts per million (ppm) and perhaps substantially higher.

For most of human history, carbon dioxide levels stood at around 285ppm. They have now passed 400ppm. By the century’s end, if humans go on burning ever greater quantities of fossil fuels to drive global heating, then these could reach 1000 ppm.

The last time that happened, during a period known as the Early Eocene 56 million years ago, the surface temperatures became up to 9°C hotter than today. The period has been repeatedly explored as a lesson for the pattern of events that might follow from global heating by profligate combustion of fossil fuels.

“The temperature response to an increase in carbon dioxide in the future might be larger than the response to the same increase in CO2 now. This is not good news for us.”

The polar ice melted. Antarctic ocean temperatures reached 20°C. Sea levels rose dramatically, oceans became increasingly acidic, mammals evolved to smaller dimensions and crocodiles haunted the Arctic.

It is a principle of geology that the present is a key to the past – and it follows that the past must contain lessons for the future. So climate scientists have always taken a close interest in the Early Eocene.

US scientists report in the journal Science Advances that, for the first time, they were able to simulate the extreme surface warmth of the Early Eocene in a computer model. After decades of geological investigation, there is not much argument about the real conditions 56 million years ago, and the immensely high levels of carbon dioxide. What is not clear is quite how the link between atmosphere and temperature in that vanished era must have played out.

Research of this kind is based on mathematical simulation, which is only a tentative guide to what might actually happen on a rapidly changing planet, but the scientists count their results a success. Previous attempts have simply been built around the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Temperatures too low

This study managed to incorporate models of water vapour, cloud formation, atmospheric aerosols and other factors that would have set up a system of feedbacks that might lead to the sweltering tropics and the very warm polar regions of the era.

“For decades, the models have underestimated these temperatures, and the community has long assumed that the problem was with the geological data, or that there was a warming mechanism that had not been recognized,” said Christopher Poulsen, of the University of Michigan.

His co-author Jessica Tierney of the University of Arizona said: “For the first time a climate model matches the geological evidence out of the box − that is, without deliberate tweaks made to the model. It’s a breakthrough in our understanding of past climates.”

Other scientists have already predicted that what happened in the Early Eocene could turn out to be a lesson for what is happening now. The finding may play into the larger puzzle of something called “climate sensitivity”: that is, how so much extra carbon dioxide might lead to so much average global temperature rise?

Risk of underestimation

Researchers have assumed that one would be in step with the other. But the latest finding also raises the possibility that warming might indeed accelerate as carbon dioxide concentrations rise. So far, the world has warmed by around 1°C in the last century, with the planet perhaps on track to pass 3°C by 2100.

But more recent studies have warned that this could be a serious underestimate. The lesson of the Early Eocene, a period of change that played out over hundreds of thousands of years, is that the questions of climate sensitivity have yet to be settled.

“We were surprised that the climate sensitivity increased as much as it did with increasing carbon dioxide levels,” said Jiang Zhu, of the University of Michigan, who led the study.

“It is a scary finding because it indicates that the temperature response to an increase in carbon dioxide in the future might be larger than the response to the same increase in CO2 now. This is not good news for us.”

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.