The Paradox of a McKinley Populism

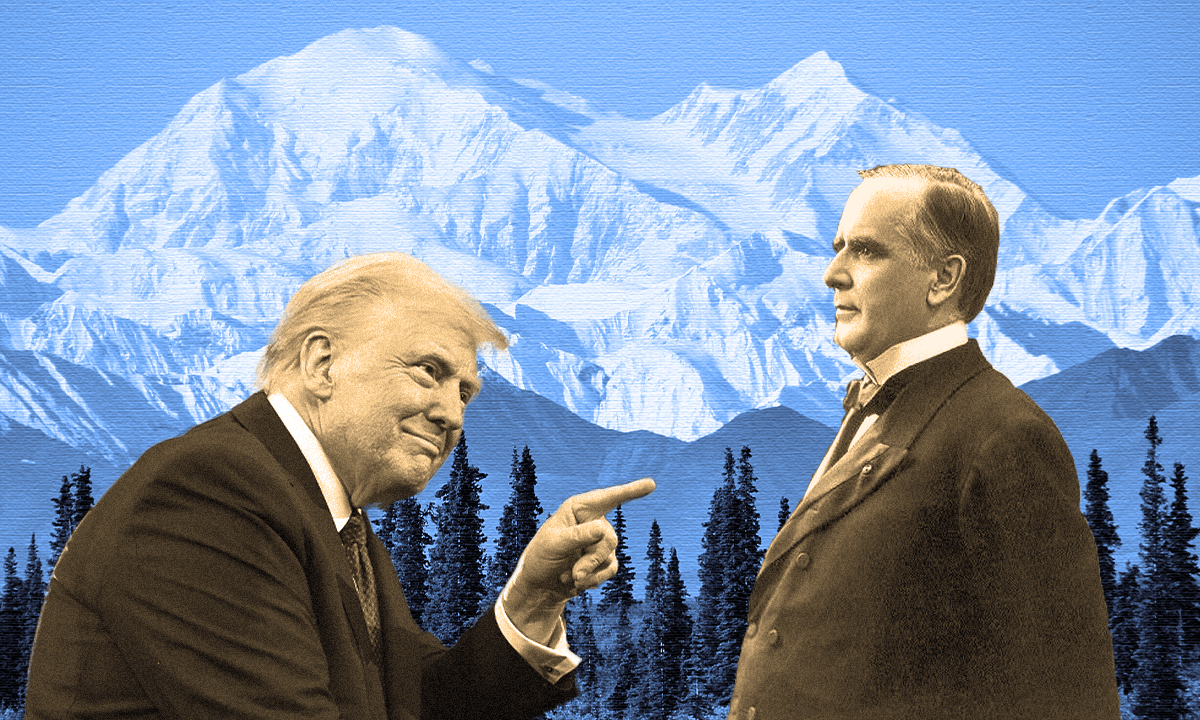

Trump’s idea of a new American golden age looks very much like the 1890s. That's not good news. What does Donald Trump's obsession with William McKinley mean for his brand of populism? (Graphic by Truthdig. Images sourced via AP Photo and Adobe Stock)

What does Donald Trump's obsession with William McKinley mean for his brand of populism? (Graphic by Truthdig. Images sourced via AP Photo and Adobe Stock)

During his first term as president, Donald Trump often pointed to Andrew Jackson as his favorite predecessor. He hung the seventh president’s portrait in the Oval Office, visited the Hermitage to commemorate Jackson’s 250th birthday and even delayed the planned removal of Old Hickory from the $20 bill. Trump looked to the 19th century leader as a model for his own presidency and proudly compared his surprise victory to the rise of Jackson, who led his own populist revolt against the “elites” in the 1820s. In his second term, however, Trump may find the blueprint for his new administration in another president of the 19th century.

Trump has been very open about his admiration for the “great” and “highly underrated” William McKinley, who he has frequently invoked in support of his plans for his second term. While the 25th president can hardly be considered a proto-Trumpian figure in terms of his personality or political style, his political and economic legacy has much that appeals to the newly elected president. Throughout his campaign, Trump presented McKinley’s economic program — particularly his commitment to protectionism — as a model for his own. While outlining his own plan to raise tariffs across the board in an address to the Economic Club of New York last September, Trump quoted McKinley as saying that tariffs made “the lives of our countrymen sweeter and brighter.”

But Trump’s fascination with McKinley goes deeper than just tariffs. Indeed, Trump is not just a fan of McKinley but of the entire McKinley era. He has often made historically and economically dubious claims about the final decades of the 19th century, depicting the period as a kind of golden age for American capitalism. “You go back and look at the 1890s, 1880s, McKinley, and you take a look at tariffs, that was when we were proportionately the richest,” Trump said in October.

Trump is not just a fan of McKinley but of the entire McKinley era.

This singular focus on the final decade of the 19th century as a period worth emulating is an especially curious choice for a politician who has long been billed as a populist. Far from the idyllic period that Trump seems to think it was, America at the end of the 19th century was an era consumed by class conflict and staggering levels of inequality. It also witnessed one the worst economic downturns of the 19th century.

“The United States suffered a devastating economic depression after the Panic of 1893, the result of mis-investment in the railroad industry,” economic historian and author of “Ages of American Capitalism,” Jonathan Levy, told me. “It was a decade marred by high unemployment, bankruptcies and deflation.” Though Trump never specified what he means when he says that the U.S. was at its “richest” in the 1890s, the available data doesn’t even come close to supporting this claim. The United States’ per capita gross domestic product actually declined in the mid-1890s, falling to less than $6,000 (in 2017 dollars), compared to roughly $66,800 per capita in 2023 (also in 2017 dollars).

Today, the Gilded Age is mostly remembered for its titanic inequalities and the robber barons who epitomized the period. This may be another reason why Trump — a rich plutocrat whose inner circle includes modern-day robber barons like Elon Musk and Marc Andreessen — looks back fondly to the McKinley years. Late 19th century America is particularly appealing to our current plutocrats for its lack of income and corporate taxes as well as the almost nonexistent regulation of business. In the 1890s, we were “a smart country,” Trump said on the campaign trail, because we had “all tariffs” and no “income tax.” There’s no reason why we can’t do this again, he suggested.

This fantasy of replacing income taxes with higher tariffs is a deeply unserious proposal that would trigger retaliatory tariffs, runaway inflation and possibly a global recession. But it does shine a light on the motivations behind Trump’s economic project and the right’s obsession with dismantling the “administrative state.” It is worth remembering, said Levy, that “the movement to replace the tariff with an income tax in the U.S. largely focused upon using the income tax to assault concentrated corporate power, which increased after the Great Merger Movement.” If the movement to replace tariffs with income taxes as the main source of government revenue was part of a broader effort to curb corporate power and inequality in the early 20th century, then the goal of reversing it comes from the obverse impulse: to further entrench corporate power and enrich the wealthiest among us.

Trump’s nod to McKinley isn’t limited to his push for a return to 1890s-style economic policies. Indeed, the president-elect’s threat to forcibly annex the Panama Canal and Greenland this month echoes an even darker feature of the McKinley years, when the country embarked on its first real imperialist adventures abroad. “During a ravenous 55-day spree in the summer of 1898, the United States seized control of five far-flung lands with a combined population of 11 million: Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba,” recalled journalist and historian Stephen Kinzer in a recent column responding to the president-elect’s expansionist threats. Trump appears eager to “go back to the old days when the United States simply grabbed what it wanted in the world,” wrote Kinzer.

In those days, expansionists were eager to present their overseas adventures in benevolent terms. McKinley defended the invasion of the Philippines by insisting that the Americans were “emancipators” acting “under the providence of God and in the name of human progress and civilization.” While multiple forces drove American imperialism at the turn of the century, expansionism was widely seen by elites as an opportunity to open up markets overseas. By mid-decade, notes one prominent historian, “many individuals and groups were stressing the importance of expansion as a way to solve domestic economic problems.” The Philippine War would last over three years and leave hundreds of thousands of civilians dead — far more “than in three and a half centuries of Spanish rule,” Kinzer writes in his book ”The True Flag.”

Though Trump has described his expansionist goals as necessary for national security and “protecting the free world,” the real reasons are similarly economic in nature. Greenland, in particular, could yield lucrative opportunities for U.S. companies in the near future. The world’s largest island is rich in essential natural resources such as oil, lithium and rare earth metals, and they will become increasingly accessible as climate change melts its bordering ice sheets. The disappearing ice caps in the Arctic could also open up trade routes in the years ahead, making Greenland even more strategically important.

If Trump’s vision of a golden age looks anything like the 1890s, it promises a grim future.

Before refusing to rule out using force to annex the Panama Canal and Greenland during his recent press conference, Trump confidently proclaimed that we are “approaching the dawn of America’s golden age.” But if Trump’s vision of a golden age looks anything like the 1890s, it promises a grim future. The most “obvious parallel” between that decade and today, Levy tells me, is “the influence of unchecked corporate power and, through this vehicle, the extreme amassing of power and wealth by a select few individuals.” If anything, today’s oligarchs have already amassed more wealth and power than the robber barons of McKinley’s day, and their grip will only tighten under the new administration. What looks like a golden age for the billionaire elite resembles a new Gilded Age for everyone else.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.