The Smoke Is Clearing

This week marks a decade since a consortium of state attorneys general negotiated the landmark settlement of lawsuits against tobacco companies. The results are in: Cigarette consumption has declined by 28 percent in the past 10 years.It was “a sophisticated, white-collar crime instigated by contingency-fee lawyers in pursuit of unimaginable riches,” according to the libertarian Cato Institute. Or perhaps it established “entrepreneurial private litigators as a fourth branch of government,” as Reason magazine warned.

This week marks a decade since a consortium of state attorneys general negotiated the landmark settlement of lawsuits against tobacco companies. The deal stirred conservatives into such a froth that they all but promoted the Shakespearean proposition that we kill all the lawyers.

The lawyers survived, and that is a good thing. The settlement they engineered is helping to save millions of lives and billions in health costs. It may well be the most significant advance in the campaign to curtail tobacco use since the 1964 surgeon general’s report.

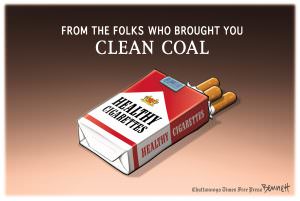

The agreement, at bottom, forced the companies to stop lying about their record of spreading death and disease for profit. It put public health ahead of private gain, a rare achievement in an era that has been shaped so indelibly by the pursuit of wealth rather than the promotion of the general welfare.

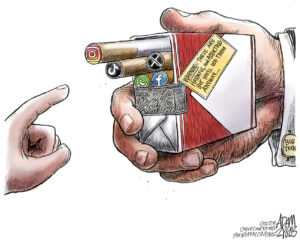

The settlement drastically limited the industry’s ability to market cigarettes to young people — the strategy Big Tobacco was using to hook new generations of smokers in order to replace those who were dying off. The pact also banned outdoor advertising, promotions in public transit facilities and the use of cigarette brand names and logos that commonly festooned merchandise as if the killer products had the same cachet as a designer’s initials.

The results are in: Cigarette consumption has declined by 28 percent in the past 10 years. The proportion of 12th-graders who are smoking is at a record low of 22 percent — down from the 37 percent high reached in 1997. “The landscape around tobacco use has shifted significantly,” says the American Legacy Foundation, an anti-smoking group funded with money from the settlement.

Travelers this holiday season will fly on smoke-free planes — a clean-air environment so expected now that it’s startling to recall that smoking aboard aircraft was permitted as recently as 2000. Most major airports will be smoke-free.

Sixty percent of Americans now live in localities that have clean indoor air laws, according to Cheryl Healton, president of the American Legacy Foundation. In fact, the steepest one-year drop in cigarette consumption occurred between 2006 and 2007 — one possible result, Healton says, of a quickening in the trend toward municipal regulation of indoor smoking.

“Basically there are fewer and fewer places where you can smoke, and people are feeling more and more guilt about smoking at home or allowing people to smoke in the home,” Healton says. “There is a lot of data that shows even in a home with a smoker, the smoker is smoking outside.”

No single, positive development is solely attributable to the controversial litigation that the states undertook. In particular, government studies confirming the health consequences of breathing second-hand smoke were crucial to the enactment of indoor air rules.

Yet without the forced disclosure of thousands of pages of tobacco industry documents that showed the unseemly truth behind the companies’ relentless marketing campaigns aimed at the young, it is difficult to imagine that the industry would have been forced to limit even its most disturbing tactics. Indeed, the current advertising restrictions are not without loopholes: Public health officials are incensed at a current Philip Morris campaign to promote Virginia Slims Super Slims Lights in pink “purse packs,” a lure transparently aimed at young women.

There is, however, a certain justice in having the industry forced to finance anti-smoking campaigns directed at the young. And justice, in the best and most democratic sense, is why the tobacco lawsuits were brought to begin with.

For decades, no amount of health research was frightening enough to force Congress’ hand. No expenditure to treat smoking-related diseases through Medicare, Medicaid or other health programs was sufficiently enormous to catch the attention of most lawmakers. They dawdled in the haze of obfuscation the industry created.

There was no get-rich-quick scheme concocted by greedy lawyers that prompted the states to pursue Big Tobacco in court. The impetus was a failure of democracy, and the outcome has been both democratic — and healthy.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2008, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.