The Unbreakable Bond of Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell

The sportscaster and boxer were cut from the same cloth. While Cosell didn’t dodge punches like Ali, both men lived with unflinching integrity.

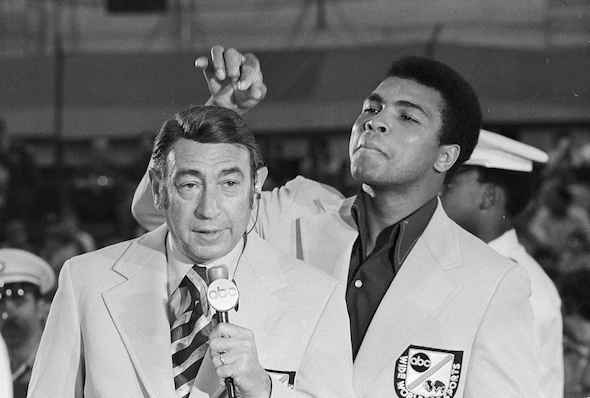

Muhammad Ali jokes with television sports commentator Howard Cosell before the start of the Olympic boxing trials in West Point, N.Y., Aug. 1972. (AP)

I wonder how many young people watching news coverage in the wake of Muhammad Ali’s death could identify the balding, sharp-tongued fellow holding a microphone to Ali’s face at nearly every important juncture of the champ’s career. Like Cassius Marcellus Clay, Howard William Cohen changed his name and became famous.

As Howard Cosell’s best biographer, Mark Ribowsky, put it in “Howard Cosell: The Man, the Myth, and the Transformation of American Sports”: “There can be no overestimating how unique and even unprecedented Cosell’s fame was by the middle of the 1970s. He had done no less than make himself a one-man industry by turning scabrousness into an endearment.”

No big fight from the late 1960s through the early 1980s — most of them on “ABC’s Wide World of Sports” — was complete without Cosell’s erudite and abrasive commentary. In some of them, he used phrases that have gone into the lexicon, such as his raucous cry of “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” when George Foreman won the heavyweight title from Joe Frazier in 1973.

“Monday Night Football” became an institution with Cosell as lead commentator from 1970 to 1983. He irritated so many viewers that as soon as the theme song began to play, millions of American males would threaten to watch the game with the sound turned down. But I never turned the sound off, and admit it, neither did you.

We watched because he was willing to talk about issues that other sportscasters avoided. And also because he had a wonderful, self-deprecating sense of humor that delighted in giving a platform to those who mocked him. Once, on a Monday night game, the camera zoomed in on a bed-sheet banner, which read, “Will Rogers Never Met Howard Cosell.” (Rogers, the humorist and social commentator of the 1920s and early 1930s, had once said, “I never met a man I didn’t like.”)

Off camera, you could hear a chuckle followed by Cosell’s only comment: “Just make sure you spell the name right.”

Arrogant, tempestuous and brilliant, Howard Cosell dragged sports journalism kicking and screaming into an era when electronic media began to supplant print.

Born in 1918 to Isidore and Nellie Cohen and raised in Brooklyn, Cosell studied law at New York University but floundered for years, trying to find his niche. He finally found it in 1956 with a radio show, “Speaking of Sports,” sponsored by a relative who owned a shirt company.

After waiting so long for his break, Cosell pursued stardom with a vengeance, bringing the big guns of a scathing, contrarian wit and bludgeoning pomposity to bear on sports’ sacred cows, such as International Olympic Committee head Avery Brundage and baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn. He made more enemies than friends with his aggressive interviewing style—New York Yankees manager Ralph Houk famously compared Cosell to excrement, telling him, “You’re everywhere.”

Cosell didn’t care. A tireless self-promoter, he ignored his critics and pressed onward. But if you paid attention to him, you couldn’t deny that there was a hard kernel of integrity in his bluster.

He wasn’t alone in supporting Muhammad Ali in his fight against the U.S. government to avoid the draft, but he was the most vociferous, and since he had just begun to broadcast television sports for ABC, he had the most to lose. He called the former Cassius Clay by his new name, Muhammad Ali, before anyone else except Ali and his mentor, Malcolm X, and received death threats for doing so, just as Ali did. But unlike Ali, Cosell had no bodyguards.

In 1970, he supported Curt Flood, who sued Major League Baseball in an attempt to become a free agent. In 1982, when Larry Holmes won a sickeningly one-sided decision over Randy “Tex” Cobb, Cosell decried the ethics of boxing commissions that would allow such matches. He swore to quit broadcasting boxing and kept to his word.

The irony of Cosell’s life is that he became rich and famous broadcasting sports but yearned for the more serious journalistic work that probably would have stifled his individuality. He lost the “Wide World of Sports” job to the much more pleasant Jim McKay and never got over the bitterness when his longtime supporter at ABC, Roone Arledge, chose McKay again instead of him to cover the massacre at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Sportswriter Jerry Izenberg, who often ghostwrote Cosell’s radio and TV commentary, thought, “It ate him up that he wasn’t the focal point when it all happened.”

Cosell was so truculent—to use one of the words he often called Muhammad Ali—that when ABC arranged a farewell dinner for him in 1986, he told the network head, “I don’t want to be honored. If you want to talk about my departure, talk to my lawyer.”

He had no successors. “His coda,” Ribowsky wrote (correctly, I think), “more than anything else is his singularity—a long-lost quality in the postmodern culture that has wiped men like him off the slate.” Cosell made his own mold, and then broke it. He had any number of imitators, most notably ESPN’s Chris Berman, who co-opted—though in obvious homage—Cosell’s signature call of a long touchdown run: “He could … go … all … the … way!” Some called him a parody of himself. Many comics did spot-on Cosell impressions. The best were SCTV’s Eugene Levy (watch him here with Rick Moranis as Dick Cavett) and Billy Crystal (here recalling his favorite Ali-Cosell moments for David Letterman).

None, though, could do Cosell with the same zeal and élan as Cosell himself. Woody Allen, a fan, knew it and chose to cast Cosell as himself in both the opening and closing scenes of “Bananas” (1971).

Allen also took an affectionate jab at him in his 1973 film, “Sleeper.”

Late in 1994, a few months before Cosell died, Frank Deford wrote of visiting him at his New York apartment. Cosell, he wrote, was “wandering” aimlessly around, picking up framed photos and mementos he had accumulated over a lifetime in sports. Occasionally he would pick something up and mumble a “few meaningless words” and move on to something else.

Then Cosell picked up a statue of Ali and held it to his chest, “Life,” Deford wrote, “came to his eyes, and he even spoke my name.”

“Frank, Muhammad gave me this. Muhammad Ali. He did. Himself.”

I don’t buy it. Incidents like this used to spring up in many of Deford’s stories, sentimental anecdotes that only Deford was there to hear, in which the subject uttered his first name, thus pulling the writer into the story.

Still, there’s probably something to Deford’s tale, if only that Cosell cherished his friendship with Ali to the day he died and that he lost his heart for boxing when Ali quit the ring. (Cosell’s much-publicized departure from boxing broadcasts came less than a year after Ali’s last fight in 1982.) When Ali died two weeks ago, ABC World News noted their special relationship.

There were times Cosell seemed to imply that they were equally immortal, but that, of course, could never be. Muhammad Ali’s image is everywhere with us—on TV, in books and on the internet. Howard Cosell, despite his undeniable impact on sports for nearly a quarter of a century, has largely faded from popular culture.

George Bernard Shaw once noted that the reputations of even the greatest stage actors of his time were, no matter the actor’s stature, “writ on water.” So it is with sportscasters. But Ali would have been the first to concede that those who pay tribute to him should pause and nod in the direction of Howard Cosell who — even if he didn’t dodge punches — at least dodged some of the same bullets as his friend.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.