The Unwomanly Face of War

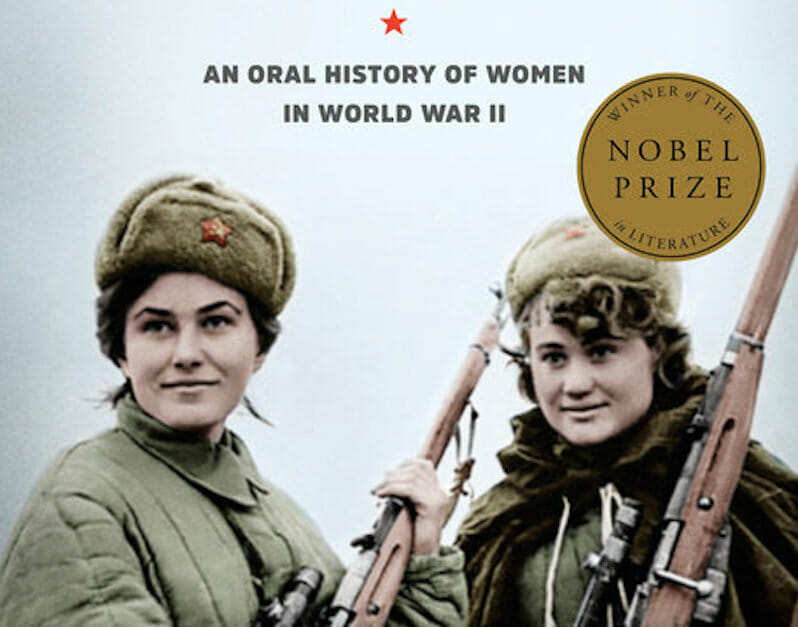

Svetlana Alexievich's first book, a harrowing oral history of women in World War II, is now available for the first time in English. (Penguin Random House)

(Penguin Random House)

| To see long excerpts from “The Unwomanly Face of War” at Google Books, click here. |

“The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II” A book by Svetlana Alexievich, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Reviewed by Elaine Margolin

Nobel-Prize winning author Svetlana Alexievich grew up in Belarus, the daughter of a father consumed by certainty and a sense of purpose. He fought in the Battle of Stalingrad where he lost two brothers during the Second World War. He was an enthusiastic Communist until his death. He saw the socialist vision as a noble one that valued self-sacrifice and concern for the weak and rejected wealth and materialism. One of Alexievich’s most troubling memories is confronting her father as a young woman when her zeal for Communism collapsed. She had just finished writing a masterful work about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The book, “Zinky Books: Soviet Voices from a Forgotten War,” recounted the massive Soviet casualties suffered, and the state’s continued lies about the numbers of the dead. The book also delved into the other atrocities committed by the Soviet Army. When a young Alexievich told her father what she had discovered, and her new feelings about the Soviet regime, he turned away from her silently. He remained steadfast to the system he had devoted his life to.

The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II

Purchase in the Truthdig BazaarAlexievich was born in 1948, shortly after the war, to a Belarusian father and a Ukrainian mother. Her parents were both teachers. Eleven of their relatives, including children, were burned to death by the Nazis in a village church. Alexievich was fascinated by the war and its aftermath as a young child. She would listen to the village women discuss it at night. Their stories made her want to know more. She was distressed when perestroika arrived and the citizenry seemed unable to move quickly enough to make the changes so desperately needed to their decaying society. She believed they simply did not understand how to go about creating a democratic world; it was foreign to them and they were mortified by the chaos and anarchy that quickly followed.

She tells us that even after records were unsealed in the 1980s and horrific secrets spilled out about the gulag and collectivization and forced resettlements, most of them remained loyal to the Communist dream. It was all they knew. Even today, she informs us that there is a new cult of Stalin percolating amid university students who believe the dream still lives on. She connects Putin’s popularity to the Russian craving for order and pride and greatness that has now been sprinkled with Russian Orthodoxy for good measure.

In her book, “Second-Hand Time,” Alexievich attempted to penetrate the mystery of the Soviet soul. She wrote, “Communism had an insane plan: to remake the ‘old breed of man,’ ancient Adam. It really worked. Perhaps it was Communism’s only achievement. More than 70 years in the Marxist-Leninist laboratory gave rise to ‘Homo sovietus.’ Some see him as a tragic figure. I see him as a Sovok. I feel I know this person; we’ve lived side by side for a long time. I am this person. And so are my acquaintances, my closest friends, my parents. Homo sovietus isn’t just Russian: He is Belarusian, Turkman, Ukrainian, Kazakh. Although we now live in separate countries and speak different languages, you couldn’t mistake us — we’re easy to spot. People who have come out of socialism are both like and unlike the rest of humanity: We have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes and martyrs. The stories we tell ourselves are full of jarring terms — ‘shoot,’ ‘execute,’ ‘eliminate’ — or typically Soviet varieties of disappearance: ‘arrest,’ ’emigration,’ ’10 years without the right of correspondence.’ ”

In another one of her seminal works, “Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster,” she wrote about the fallout from the infamous explosion. Once again, the Soviet authorities uttered countless lies about the disaster to cover their tracks, lies that exacerbated the suffering of those in the radiation zone. Alexievich spent years interviewing the survivors. One man who was called to the Chernobyl site for cleanup came home and placed his fireman’s hat on his 5-year-old son’s head. The child died soon afterward from the radiation his father’s hat emanated.

Alexievich’s books are brilliant and painstakingly constructed montages of oral testimonies. For each project, she generally interviews between 500 and 700 people, often visiting them more than once. She then begins to edit and compress their testimonies into a narrative that preserves the integrity of their voices. She blends journalistic inquiries with literary flourishes, creating her own unique blend of narrative. The results are spellbinding — a chorus of voices that are usually presented with little context; often just a name and occupation, and sometimes not even that. She is interested in the pivotal moments of people’s lives — the incidents that emotionally shaped them.

In her first book, “The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II,” now available for the first time in English in a translation by Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear, she writes movingly about the 1 million women who served in the Red Army as snipers, medics, foot soldiers, pilots, tank drivers, mechanics and other vital jobs. She explores difficult terrain. What is it like to kill someone? What were they most afraid of? How have they dealt with their traumas? What effect has their war experiences had on their children and grandchildren?

She observes that women remember war differently. They do not focus on heroics or the intricacies of battle as men do. Little moments remain etched in their memory and change them forever. This is what interests Alexievich, who calls herself a “historian of the soul.” The book was written in the early 1980s, but had to wait for Gorbachev to be published, after which it sold millions of copies in Russia. Its new English release overwhelms the reader with its harrowing memories recorded four decades after the service of the women in the book’s pages. One woman cannot speak about it and only whispers softly into Alexievich’s ear, “I killed so many…” before asking Alexievich to leave. Another woman recalls the magnificent beauty of the silent mornings before battle. Still another remembers how upsetting she found it that she didn’t ever see flowers or birds during the war, only blood and darkness. Many others are more than willing to talk, often for hours upon hours, relieved to finally unravel what they have long repressed.

Antonio Grigoyevna Bondareva weeps about losing her husband in 1941. After his death, she volunteered to serve, leaving her daughter with her husband’s parents. She explains her decision with a still resonant clarity: “The Motherland was everything, the Motherland must be defended.”

Yenia Sergeevna Osadcheva volunteered in 1942 and admits she “changed so much during the war that when I came home, Mama didn’t recognize me.” She believes the trauma she suffered is now etched into her physical being, claiming “I live in Crimea. … Here everything drowns in flowers, and every day I look out the window at the sea, but I’m worn out with pain, I still don’t have a woman’s face. I cry often, I moan all day. It’s my memories. …”

Very Borisovna Sapgir addresses the perpetual guilt that never leaves her. “Fortunately I … I didn’t see those people, the ones I killed … but … all the same …now I realize I killed them. I think about it … because … because I’m old now. I pray for my soul.”

Natalya Ivanovna Sergeeva, who served as a nurse, speaks about finding empathy in her heart for a captive German soldier, explaining how she once felt compelled to break off a piece of bread and hand it to him. Another woman who is unidentified remembers that the “war had three smells: blood, chloroform, and iodine.” Yet another remembers that upon finally arriving home, she was obsessed by dreams of the pleasure she would reap sleeping in her own bed on white sheets while eating entire loaves of bread. But the reality was that for many years after the war she felt tormented by her memories.

Not all of the women had regrets. Tamara Lukyanovna Torop was a private and construction engineer during the war. She explains that she and her father were both weaned on the love of Soviet power and Stalin. She writes candidly: “Papa’s long gone, but I continue to love him. I don’t believe it when people say that men like him were stupid and blind, believing in Stalin. Fearing Stalin. Believing in Lenin’s ideas. Everyone thought the same way. Believe me, they were good and honest people, they believed not in Lenin or Stalin, but in the Communist idea. In socialism with a human face, as they would call it later. In happiness for everybody. For each one. Dreamers, idealists — yes; blind — no. I’ll never agree with that. Not for anything! …”

Alexievich’s presence, like the most skilled of documentarians, is often barely felt. Occasionally, she offers some direct commentary, describes to us how a woman is sitting, or the expression on her face. She notices that when men are present, women speak less candidly. When many people were in the room, certain patterns emerged. The woman would usually become more defensive and her testimony would be passionless and sterile. She would try to gently steer the conversation back to the incomprehensible truths that guided their lives during and after the war. We sense her empathy competing only with her curiosity.

Svetlana Alexievich today lives in Minsk, Belarus, near her adult daughter. She takes pleasure in being near her child and granddaughter. She won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015. Yet she is officially unrecognized by the state, and Putin ignores her due to the harsh criticisms of his regime that are scattered throughout her many groundbreaking books. She has said in interviews that she has spent too much time immersed in the sadness and grief of others, and would like to write a book about love — something she admits she has not always been lucky at. But one senses she will drift back to telling the story of the Soviet state and the many Soviet souls who feel unmoored from its demise. It is her father’s lost world, and her own.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.