The War of the McCourts

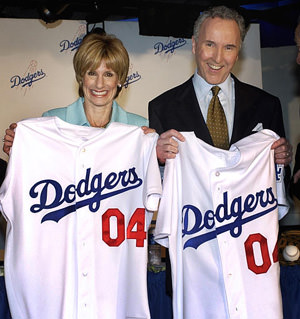

The story of Frank and Jamie McCourt, who turned the Dodgers into their own piggy bank, lived a life of mortgaged royalty and then decided to destroy one another, is like something out of Tom Wolfe.The story of Frank and Jamie McCourt, who lived a life of mortgaged royalty and then decided to destroy one another, is like something out of Tom Wolfe.

In 1964, 29-year-old Ken Kesey finished “Sometimes a Great Notion,” a saga of a defiant Pacific Northwest logging family that was his last novel for 25 years.

To celebrate, Kesey and some friends painted an old bus the way a kindergarten class would have — starting a fashion trend for the decade — and took off for the publication of the book in New York with Neal Cassady, the model for Jack Kerouac’s hero in “On the Road,” at the wheel.

Subsequent voyages headed to Haight-Ashbury, where Kesey, who had discovered LSD as a Stanford student in a CIA-sponsored study, and his Merry Pranksters threw one of their “Acid Test” parties where you really had to watch out for the punch and where the Grateful Dead, a former jug band setting out in a new direction that would be called “acid rock,” played its first gig.

Their adventures became the basis of Tom Wolfe’s “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” If it was hard to tell what it all meant, it clearly meant something.

The War of the McCourts is like that, a lusty (with whomever), brawling (through their $1,000-an-hour lawyers) saga of a strong-willed New England family whose idea of running its new baseball team in Los Angeles includes hiring a Russian spiritualist — no, not Rasputin, he’s dead, we think — while turning the franchise upside down and shaking it like a piggy bank.

Unfortunately, at that point, the McCourts’ story takes a turn for the worse.

Frank and Jamie, who would still be fine if they had done nothing worse, split up and set out to obliterate each other.

This is about more than a lost Dodger season. This is Wolfe’s “Bonfire of the Vanities” with Frank and Jamie as dueling Sherman McCoys, and Jamie’s driver, Jeff Fuller, as Maria Ruskin, the Other Person.

If the Dodgers wound up on the bonfire, it could have happened to anyone.

Actually, it did.

Reality intruded on their blue leveraged heaven in 2008 as the housing bubble burst, threatening to melt down the financial system in what looked like Great Depression II.

Of course, Frank and Jamie lived in a galaxy far far away from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which the GOP blamed for the fall for making loans to poor people with minimal down payments.

Unfortunately for the poor, who always get the least portion and then the blame, it was hard to get into Georgetown U, where Jamie met Frank, let alone the Sorbonne and MIT, where Jamie continued her education.

Otherwise, the poor might not have put any money down … then borrowed on the property to buy more … like Jamie and Frank!

If schadenfreude is wrong — no, really — this is an extreme test after seven seasons in which it was always about them as Frank finessed the truth while doing Dodger Blue over in Boston Red Sox (Grady Little, Nomar Garciaparra, Manny Ramirez), Jamie co-owned visibly and befriended movie stars (Barbra Streisand) and image concerns were addressed by going through five publicists including Derrick Hall, who became president of the Arizona Diamondbacks; Camille Johnston, who became Michelle Obama’s spokesperson; and Dr. Charles Steinberg, now senior adviser to Commissioner Bud Selig.

Now for the big finish, a mushroom cloud rising over Dodger Stadium.

If you’re looking for someone besides the McCourts to blame … consider Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo.

If he hadn’t discovered California, the state would not have inherited the Spanish civil code and there would be no such thing as community property [so] Frank and Jamie wouldn’t have had to sign a contract when they moved here from Massachusetts … [and] wouldn’t have anything to fight about.

–Gene Maddaus, LA Weekly

If it’s hard to tell the difference these days, this isn’t a series about fictional characters, but real people named Jamie and Frank McCourt, or people who once appeared real.

How could this have happened, in general, and to them?

Unfortunately, it was simple.

No laws of man or nature had to be overcome. The devil didn’t have to come up from hell to seduce Frank and Jamie into risking all they had and then go even deeper in debt to live like the movie stars around them.

The system, or systems (legal, banking, baseball), weren’t subverted. Actually, they made it possible.

Just one thing separated Frank and Jamie from the other Type A’s running amok: They had a Major League Baseball team.

It wasn’t just any team, but the iconic Dodgers, in their iconic stadium, atop a hill overlooking downtown, where they opened the gates and 3 million people showed up.

In the seven pre-McCourt seasons — the sainted Peter O’Malley’s last and six being ignored by Rupert Murdoch, a more callous, devious scourge by far — the Dodgers had three No. 2 finishes, four No. 3s (in a five-team division) and averaged 3.2 million in attendance.

Entering the House Rupe Raped, Frank and Jamie would have been greeted like the Prince of Wales and Lady Di.

Instead, Dodgers fans got a preening Yuppie husband-and-wife team, poseurs as baseball executives, lacking in clues, sensitivity and resources.

Frank and Jamie weren’t lacking in brains, though. They knew they had this covered.Even if they had to run the Dodgers — who once shattered racial barriers and blazed trails — like a middle-market team, this wasn’t the AL East with the Yankee payroll at $200 million and the Red Sox at $150 million.

The NL West had mom-and-pop stories all in a row, even in boom times like 1993-2002 when the expansion Rockies averaged 3.6 million, or 2000-2003 when the Giants averaged 3.3 million in Pac Bell Stadium.

Scaling payroll back from $105 million to $95 million in the McCourts’ 2004 debut to $83 million by 2005, they remained 1-2 in the NL West, where no rival would venture past the $90 million mark until the 2010 Giants.

So Frank and Jamie didn’t need Branch Rickey to rise from his grave to win the NL West their first season and four of their six together.

Even if the Dodgers went quietly each time, 4-20 in four post-seasons, the establishment came around, as it always does.

Wrote USA Today’s Jill Lieber in a feature on Jamie in their second season:

Don’t think McCourt was given her position only because she is the owner’s wife. She’s running the show because she has the goods: a bachelor’s in French from Georgetown, a diploma from La Sorbonne in Paris, a J.D. from the University of Maryland School of Law and an M.S. in management from MIT. …

She also practiced law for 15 years … and raised four boys. Drew, 23, has a degree in astrophysics from Columbia and is the Dodgers’ director of marketing. Travis, 22, recently graduated from Georgetown and just joined the frontoffice. Casey, 18, will be a freshman at Stanford. Gavin, 15, attends Harvard-Westlake School in Los Angeles and was a nationally ranked tennis player.

Quite simply, McCourt is a 5-2, 100-pound, golden-blond tornado in size-0 designer miniskirts and 3-inch heels.

If Frank and Jamie were also cutting-edge New Age thinkers, they wisely kept it to themselves, as when they hired their spiritualist to send positive energy.

That was 71-year-old Vladimir Shpunt, an émigré Russian physicist who helped Jamie get over an eye infection and went on the payroll.

Shpunt didn’t claim to know anything about baseball and didn’t attend games, sending the Dodgers energy while watching them on TV from Boston.

Few team officials or players are thought to have known about Shpunt. The Los Angeles Times’ Bill Shaikin broke the story before the trial, which was confirmed by another Jamie biggie, entertainment lawyer Bert Fields (Beatles, Michael Jackson).

Not that it was an issue between the McCourts. The Times quoted Frank after clinching the NL West in 2008, e-mailing Shpunt’s agent:

“Congratulations and thanks to you and vlad. Also, pls pass along a special ‘thank you’ to vlad for all of his hard work.”

Energy wasn’t everything. The Phillies then dispatched the Dodgers, 4-1.

This was also their house-acquisition phase … a $20 million mansion and a $6.5 million cottage next door for a guesthouse in Holmby Hills across from the Playboy Mansion … adjacent homes on the beach at Malibu at $19 million and $17 million … a $4.6 million lot in Cabo San Lucas … to go with those in Brookline, Vail and the $20 million one on 100 acres in Cape Cod.

Their debt level was staggering but times were booming and they owned the Hope diamond of properties, which they had picked up in a garage sale.

Buying the Dodgers had helped Murdoch pre-empt a Disney challenge to his regional sports networks, but became a PR debacle and, he claimed, a financial one.

Since Murdoch was effectively taking money from the Dodgers and giving it to Fox, no one could tell how much — or if — he was losing.

Murdoch himself couldn’t have cared less but he did let his lieutenants atop his media empire take a crack at running the team. Six weeks into the season, they traded catcher Mike Piazza — who wanted a new $100 million deal after averaging .334, 33 home runs and 105 RBIs in his first five seasons — to Miami after calling the Marlins to discuss a TV matter.

After six years of screwing the pooch, Murdoch secured the TV rights for 10 more years in a sweetheart deal — with himself — and went looking for a buyer, even one he had to loan half the $421 million purchase price, it turned out.

What cash the McCourts needed came in loans on their 24-acre parking lot in Boston. Essentially they traded it for the Dodgers, with a promise to pay off the difference.

What could go wrong now?

Selig, partial to leveraged owners who wouldn’t run up $200 million payrolls, embraced the McCourts, vetting their complex transaction and showing no interest in L.A. white knight Eli Broad’s late overture.

Sure enough, raising revenue was a snap for Frank and Jamie, who wrung every last dollar out of every square inch, whether it was real or an accounting device.

Parking was hiked from $10 to $15, infuriating fans who lived miles away, had to drive and had two choices: fork up or stay home.

They could charge their own team $14 million to play in its own stadium, spun off to a McCourt-owned entity called Blue Land.

Like so many other scoops, the rental was revealed before the trial with David Boies, Jamie’s lead lawyer, telling Shaikin, “It’s a way of taking money out of the Dodgers and putting it into a place they can access it.”In court papers, the McCourts were alleged — by Jamie’s lawyers — to have taken out $108 million in personal distributions.

There was only one thing Frank and Jamie apparently didn’t do — break any law.

Amazingly, despite the scope of the wheeling and dealing, there have been no allegations they did anything illegal.

Suppose you were so slick, no matter how many hundreds of millions you owed, you could go out and borrow hundreds of millions more.

You just might try to find out how many yachts you could water-ski behind, like Gordon Gekko, Frank and Jamie.

Where do companies turn when you-know-what hits the fan? Say for example, when FBI agents invade your offices or an out-of-state bank refuses to renew your credit line that is keeping the company and the economy afloat? Two companies with these actual problems had one answer: Michael Sitrick.

— CFO magazine

And just as amazingly, no one was on their trail.

No one would have even known about the McCourts’ wanton juggling act if they had done only one thing …

Stay together.

Unfortunately, it can be hard to split the loot with the heat coming down on you, as times changed and the boom burst.

Now the marriage, which had featured stormy confrontations, had a crack in its foundation.

Upon buying the team in 2004, Frank and Jamie had signed a property agreement in which she gave up any claim to the Dodgers for title to all their other property, which may be why they bought so much more property.

In later years, Jamie, aware the team’s value would skyrocket in 2014 when it regained its TV rights from Fox, pressed Frank to reapportion their property.

Frank was willing but estate planning foundered on the issues of Jamie’s claim to the team, and the team’s value.

As in any negotiation, there was a doomsday scenario — divorce — although Jamie’s estate lawyer, Leah Bishop, advised her client (in an e-mail that would be filed in court papers) that that was “the nuclear option.”

Only Jamie and Frank know when they had it with each other, and their versions differ by 180 degrees.

In any case, while figuring out who got what, they split up.

In 2009, they took separate vacations. Jamie went to Cape Cod with Fuller.

A day after the Dodger season ended, Frank fired Jamie from her $2-million-a-year CEO post, noting “inappropriate behavior with regard to a direct subordinate.”

Jamie tacitly acknowledged the affair with Fuller, telling the L.A. Times’ T.J. Simers that it didn’t begin “until the marriage broke up.”

So started the Mutually Assured Destruction phase.

Within weeks, TMZ reported Jamie had called 911 to keep Frank from entering their Holmby Hills home.

Frank’s lawyers issued a statement saying he was jogging by when he found “his wife swimming in the pool and her personal ‘security assistant,’ Jeff Fuller, was also at the residence.”

Jamie’s lawyers denied Fuller was there.

On Aug. 30, after 10 months of not settling this before it really got ugly, the trial began, making up in sensation what it seemed to lack in merit.

Jamie’s case is based on her insistence that she didn’t understand the 2004 property agreement — incredible as that sounds, as Jamie herself noted.

In a 2008 e-mail to the Boston attorney who drafted the document, and backed Frank’s understanding, Jamie wrote:

“Don’t forget, I was a divorce lawyer there and I am really clear on what the intended distributions were to be.”

In the same e-mail, Jamie acknowledged that it was “my fault, I guess, for not having read the post marital document and believing that you were preserving the status quo.”

This seemed to leave Boies a who-are-you-going-to-believe-me-or-your-eyes defense with worse odds than he had with Al Gore before a Supreme Court with five justices wearing “W.” buttons.

Jamie went for it anyway, pouring hundreds of thousands of dollars into a vintage Sitrick PR campaign, sitting down with anyone who mattered, even Simers, who had referred to her as “the Screaming Meanie.”

(As Kathleen Turner sneers in “The War of the Roses” when Michael Douglas tells her to get a good lawyer, “Best your money can buy.”)

With Frank silent, stories tended to be sympathetic narratives of what went through Jamie’s mind when this and that happened, which hardly changed the basic equation.

Wrote ESPN magazine’s Molly Knight of Jamie’s ability to remember the exact time she saw Frank’s e-mail firing her on her BlackBerry, but not where she was:

“She was alone in her home, yes, but which one? It was hard to keep them straight.”

So much for the PR war.

If defendant and claimant were pariahs, the trial was a gift from the gods as the cream of U.S. jurisprudence acknowledged their own clients’ excesses, secrets and lies.

It was Steve Susman, Frank’s lead attorney, who asserted the McCourts put “not a penny of cash” in the purchase, making the point that it was prudent for Jamie to trade her claim to the team for their other property.

Another of Frank’s lawyers, local divorce biggie Sorrell Trope (Elin Nordegren, Hugh Grant, Cary Grant), compared Jamie to Marie Antoinette after Jamie’s attorney, Dennis Wasser (Tom Cruise, Clint Eastwood, Steven Spielberg), set him up, detailing the royal lifestyle to justify Jamie’s request for $1 million a month.

“They lived in seven lavish homes … flew in private jets … had hairstylists come to their house every day,” said Wasser.“Every need, every want these people had was met. …

“It’s not our province to say, ‘That’s too much, that’s too little, who lives like that?’ ”

The hairstylists, it was revealed, cost $150,000 a year.

Taking it on himself to say, “Who lives like that?” Judge Scott Gordon gave Jamie $637,000 a month.

She’s still getting it, perhaps explaining why the most sensational war of attrition in divorce history was still going this week.

As Yogi Berra said, it ain’t over until it’s over.

With the trial resuming after a two-week break, Yahoo’s Tim Brown reported the two sides will begin settlement talks.

In other words, having dined on each other for a year, Frank and Jamie would now divide all they own, as everyone knew they would have to all along.

Manager Joe Torre, the team’s professionalism totem, had already resigned, noting it wasn’t necessarily a retirement.

In other words, if the Mets want him, he’s there.

Ramirez, the one Red Sox relic the McCourts brought from Boston who made a difference, was recently waived. Manny was Manny, all right, lighting up Dodger Stadium (turned into Mannywood), getting busted for steroids and no-showing in his farewell season.

People come, people go, but not systems.

Demands for meaningful federal financial reform in the wake of the economic meltdown perished in the political crossfire.

Selig has remained mum despite reports that he’s fuming at the spectacle.

Too bad Frank and Jamie let Bud down, after he escorted them to power, vouching for the viability of their offer, which turned out to have included “not a penny of cash.”

Of course, baseball runs on hope, which arises in spring. Even if Frank keeps the team, he’d have to sell it to give Jamie half their estate, unless, of course, she trusts him to run it for her.

In all likelihood, Jamie will be as anxious to see Frank sell the team as its fans are.

Rupe II, anybody?

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.