The West Has Islam Dangerously Wrong

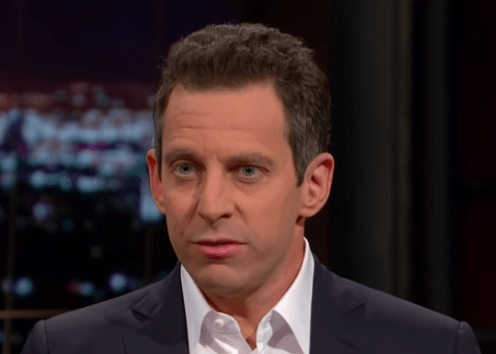

University of Michigan professor and author Juan Cole explores our biggest misconceptions about the world's second-largest religion. (Pictured: author Sam Harris.) Author and philosopher Sam Harris has advanced the idea that there’s something uniquely dangerous about the Muslim religion. (YouTube screen grab)

Author and philosopher Sam Harris has advanced the idea that there’s something uniquely dangerous about the Muslim religion. (YouTube screen grab)

Listen to his interview with Scheer or read a transcript of their conversation below:

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence.” And the intelligence comes from my guests, but also, more importantly, education. And I’m talking to Juan Cole. This is a man who has the courage actually to treat the history of the people of the Middle East as significant as any other region. So why did you decide at this point in your career to write a book, “Muhammad: Prophet of Peace Amid the Clash of Empires”? And basically you present Muhammad as a reaction to the destructiveness of all of this violence, war, tribalism that have been going on, that the Romans had brought in but that was exacerbated by regional conflicts and what have you. And he himself was an orphan, thrust in the middle of all of this. So the book argues, what, is it a provocative thesis?

Juan Cole: Well, I don’t think it’s provocative for most Muslims; the things that I say are well-known in that community. But I think it’s maybe provocative for an American and European audience, in the sense that there have been enormous numbers of polemics against Muhammad, and accounts of his life that, let us say, reflect poorly on him, which have discounted this emphasis that the Qur’an clearly has on peace-building, peace-making, striving against violent conflict. And I think it’s very central to the Qur’an, and as you say, the Iranian empire of the day invaded the Roman Empire in 603. And the Iranians invaded the Roman Near East, and a war ensued that lasted ‘til around 630. So most of Muhammad’s life was lived during that, what I call a 7th century world war. During the war, many of the Roman sources maintain that there was violence between Jews and Christians in the Near East, because Jews are alleged to have tilted toward Iran, having not been very well treated by the Roman Christian empire. And that there were synagogues destroyed, or churches destroyed in turn. And the Qur’an complains about this; it says nobody should go into any house of worship except reverently, and should not be interfering with people worshiping there, and should not be destroying those houses of worship, implying both churches and synagogues should be held holy. So I think that verse is referring to this turmoil among the Christians and Jews of this period.

RS: Reading your book, you really have a great sense of—that this is life. And it’s life in all of its complexity, with or without religion. It’s laced with religion, but religion is not coherent, really; it’s what people want to make of it, or how they interpret it in different areas. Religion is held out to be very important, in a sort of organizing idea—and then it isn’t. [Laughs] It’s divisive; Muslims fight with each other, right? They end up splitting into major splits. But we’ve seen it with other religions; Ireland, where the Protestants and Catholics find a lot to fight about. It was a Jewish assassin who killed Yitzhak Rabin in Israel. So what comes from your book is a great tale of life, but not any coherent sense of ideology from religion or power or clarity about the meaning of life or anything else.

JC: I tried to evoke the era, and to put together a meaningful narrative about the rise of the Muslim religion, which was very much embedded, I think, in the structures of its day. The Qur’an ideologically is a plea for a couple of things, centrally; one is a notion of the divine as unitary, so it is a very strongly monotheistic preaching. But a kind of world parliament of religions, or of monotheistic religions, is implied, because it promises salvation not only to believers in Muhammad’s mission, but to Jews, Christians, and anybody else who believes in the one God. As you say, however, that message still was controversial in Arabia, where I think there’s evidence of a survival of paganism. People in Arabia and Jordan were actually worshiping, still, Zeus and Athena in their local manifestations. And those people minded, apparently, Muhammad’s teaching of monotheism. But I imply that there was also a political dimension to this, because I believe the Qur’an sides heavily with the Roman Empire against the Sasanian Zoroastrians, and that the Pagans tended to be pro-Iranian. So there was, you know, a division on which horse you were backing in this big world war, as well.

RS: You know, this is going to offend you. Maybe it won’t. But I kept thinking, every time I read a book like this I think of the “Life of Brian” Monty Python movie, and I think of the whole scene of different prophets and different appeals and different claims. And reading your book, there just is a sense of a sort of teeming life—evolved around trade, around survival, around getting things from the areas where you had water to where you couldn’t grow anything, or keeping your shrine going because you could supply water. What is so great about this book, there is really a sense that life went on, and life involved a lot of haggling and a lot of difference and a lot of survival, and a lot of trying to get by. That he was thrust into the middle of all that.

JC: Oh, absolutely. Well, I’m not offended; I think John Cleese is one of the geniuses of the age, and it’s an honor to be in any way compared with him. But I think it is true that there was a lot of jostling of religious conceptions in this era. There are many arguments in this book that are not normally made, so I should signal to readers that that is—I think of it as original, but some people might consider it a departure. But one of the arguments I’m making is that the Christian Roman Empire of the 500s was still very diverse. You had a big Jewish community in Galilee and places like Tiberius. And then you had various kinds of Christians, which were not necessarily on good terms with one another. And then you still had this survival of Paganism. And not just of worship of the old gods in the rural areas, but also of Neoplatonism; you know, very sophisticated kinds of non-Christian thinking about God. And I believe that the Muslim religion emerged from that maelstrom of these various strands. And then of course, over in Iran, you had the Zoroastrian religion, which we no longer hear much about because it declined. But at that time, it ruled half the world, and also was a prophetic religion believing in a supreme deity. So this was a very, as you say, a vivid world of many religious ideas jostling with one another. It was a time of enormous imperial conflict. And the Muslim religion emerged in an attempt, I think, to solve some of these difficulties. So for instance, the Christian Roman Empire increasingly demoted Judaism, almost treating it like a form of Paganism, putting restrictions on Jews. And a couple years after the Prophet Muhammad’s death, the Roman Empire actually forbade Judaism altogether, and seemed like it was going to try to make all the Jews convert to Christianity. So there was a great deal of intolerance in that world. And one of the features of the Qur’an which I think is too little appreciated is that it’s a counterargument; it’s an argument for tolerance, at least of the monotheistic religions, of Christianity and Judaism and, I would argue, things like Neoplatonism that were monotheistic in character, and Zoroastrianism. And that, this ecumenical argument for all living together—and even, I think, it calls upon for tolerance of pagans, as long as they’re not trying to kill you, as they sometimes were. So I think it’s an extremely ecumenical book, the Qur’an, and the Prophet’s preaching of it. And that is something that’s been lost, not only in Western conceptions of the religion, but often among some believers as well.

RS: The task before you, and I’ve read some of the critical comments of readers, there seems to be a felt need to be hostile to Islam in general, whatever that means; to hold Islam accountable for most of our problems, whether they’re in France or elsewhere, and to demonize this particular religion. As an outside observer of all of these religions–let me be candid here—I think they’re all capable of nuttiness; they’re all capable of intolerance; they’re all capable of tolerance. And so I just want to basically ask you the question, should we be studying religion? Is it important to grasp it, other than to counter obvious slanders about a religion? Is there great insight? Does reading the Qur’an or studying Muhammad give us an insight into what is the meaning of life, or how to live it better, or—what is your kind of rough answer to all that?

JC: Well, with regard to the study of religion, that’s been my life, so I would defend it. I think actually that the main European and American intellectual traditions that came out of the Enlightenment often underestimated religion and, I would say, religion and spirituality as important elements in people’s lives. I’m not talking about whether they’re true or not true; I’m just talking about how important they are. And I think people like Voltaire—who was not an atheist; he was a deist—but he really had a great deal of contempt for conventional religion. And someone wrote to him and asked him what he thought about conventional religion, and they meant mainstream Roman Catholicism of the 18th century, and he said “Ecrasez l’infame”—“Crush the infamous thing.” And I think there’s a lot of that kind of attitude in the subsequent social sciences and mainstream thinking of a lot of European and American intellectuals that’s just hostile to the phenomenon in ways that are not helpful for understanding it.

RS: [omission for station break] We’re back with Juan Cole, the author of “Muhammad: Prophet of Peace Amid the Clash of Empires.” I want to stress to people listening to this, this is a really great read. You clearly love describing the lives of people—really, you can almost smell the food and hear the music. And we’re going to run out of time, and I want to get to the controversy here. The very idea of taking Muhammad, let alone the Muslim religion, seriously—as anything but a threat, as anything but a source of madness and violence and so forth. But I was reminded of a panel I tried to moderate for Truthdig where we had Sam Harris, who’s sort of made a career of criticizing the Muslim religion, in a debate. Sam Harris actually seems to have—and he’s not alone, of course—advanced the idea that there’s something uniquely dangerous about the Muslim religion. That it is—they used to argue about communism; now we have communist China, it’s not, evidently they have a different kind of communism. There was sort of an idea that this particular religion has to be hostile to others, has to be intolerant. Now of course your book challenges that idea. But it’s still probably a dominant idea, is it not?

JC: Oh, I think it’s a very widespread idea in Europe and the United States, and becoming more widespread, much to my dismay; the opinion polling is horrible. They just did a poll in Germany where they found 44 percent of Germans think that Islam should not be practiced in Germany. I think Sam Harris is not only saying something that’s factually incorrect, but also something that’s very dangerous. Any time you single out a group of people as different from others, and as posing a unique kind of danger to society, that leads in very bad directions. And we have seen over and over again in modern history the directions that it can lead. So it’s wrong, and it’s wrong-headed. And the evidence on which Sam Harris bases what he says is just misinterpreted. So for instance, there are these verses in the Qur’an which authorize what I argue is defensive war, self-defense. The first part of the Prophet’s career in his hometown of Mecca was characterized by this emphasis on peace-building, and really what you can only call turning the other cheek in the face of harassment and ridicule and humiliation. But then the community and the Prophet are under such severe pressure that they emigrate in 622 to the nearby city of Medina. And then the militant pagans come after them there, and you know, attempt to invade the city and kill them. I would argue that the first part of the Prophet’s mission, the community was more or less pacifist. But then the Qur’an starts speaking about the need to defend themselves on the battlefield if they’re attacked. And these verses about self-defense have been twisted around, not only by Western polemicists, but by Muslim extremists, to seem as though they are commanding violence. So you know, in the New Testament, Jesus at one point says don’t think that I have come to bring peace; I have come to bring a sword. And it’s as though you had Christian extremists who then went around killing people because Jesus said that. Well, it’s not what Jesus meant, and these verses are not what Muhammad meant; that is to say that the Qur’an is not arguing for aggressive action, it’s arguing for self-defense. It says, it explicitly says defend yourselves but don’t commit aggression. And it says if the enemy sues for peace, you have to make an armistice. Well, if you were fighting an aggressive war, wouldn’t the enemy always sue for peace? I mean, the only way that this verse makes any sense is that it was a defensive war. And what I argue is that there’s this peculiar blindness in Western writing about the Qur’an, and about early Islam, in this regard. That all the Qur’an is really saying is exactly what the church fathers had said. So if you read St. Augustine or St. Ambrose, or the people who formed Roman Christianity after Constantine’s conversion, they say the same thing. They say that there’s such a thing as just war, and with Augustine he was arguing against a sect called the Manicheans, who were pacifists. And the Manicheans would throw up Jesus’ words about turning the other cheek, and Augustine said well, yes, that’s true; you should turn the other cheek, but you shouldn’t take it too far, you know? If people are trying to kill your children or your family, you have to defend yourself. And the Roman army is there for that purpose. So I don’t think that actually the Qur’an is any more in favor of war than the church fathers were. And in both cases, they argued for what is called just war, which is to say wars of self-defense or of involving demands for rights. And these verses of the Qur’an are picked up by people like Sam Harris, and presented without any context whatsoever, and made to look as though Muslims are being commanded to go out and just kill random people anytime. And you know, this has had an effect on U.S. policy. So Muslims in the town of Murfreesboro in Tennessee wanted to expand their mosque, and the local city council wanted to stop them from doing that on the grounds that they might be better able to plan out murders from the mosque if it were bigger. And this is to the point of ridiculousness, and it’s one of the things that comes out of this Islamophobia of people like Harris.

RS: You know, it’s interesting, because what it reminds me is, you can say this about any group, any movement, any ideology. I mean, just take China right now—you could say, well, if you read Lin Biao’s report to the—or if you read “The Little Red Book,” or if you read—then you’d know why they want to chop everyone’s head off! And well, no, it turns out they’re brilliant capitalists. So you get these stereotypes, and it really galls me, you know, when you mention about Germany. My goodness, if there’s ever a laboratory for suggesting that a religion that some people think is a religion of peace, you know, Christianity, could also be an incubator for the most extreme violence in modern history, right? The idea that 44 percent of the people in a country that committed the worst, or inspired the worst barbarism in modern history, can now say that they can’t live with Muslims?

JC: Yeah, no, it’s very disturbing. And I brought up the statistic because I’m disturbed by it. And you never want to hear the Germans think that a religious minority shouldn’t be there, because they have a track record. Yes, it’s true, there’s false equivalencies and hypocrisy involved in this charge of Muslims being peculiarly violent. And I argue that if you took Europe in the 20th century, that between direct action and indirect consequences, they probably polished off about a hundred million people. And that the Muslim world probably only polished off two or three million in the same period. So for the Europeans to claim that the Muslims are peculiarly violent is statistically weird. Now, it is also true that the Europeans had industrialized warfare before everybody else, and also that the Muslims were mostly under European colonial rule, and so weren’t in a position to act as the Europeans did. But nevertheless, I don’t think—the idea of peaceful Europeans and violent Muslims flies in the face of everything we know about the 20th century.

RS: Let me end this by bringing it up to the present. Because when I was reading your book, I got that whole sense of, we’re always going to argue about religion, and there are always going to be—obviously—there are always going to be these intense feelings. But it struck me how the tone seemed to be very close to the present situation, particularly the Shiite-Sunni argument. Not in its exact description, of course, but the passion—who’s the false God, and who betrays the religion. And right now, when I look at the current situation, we’re being whipped around—by “we,” I mean much of the world—over what is kind of a very old argument between two branches of this Muslim religion. Right? Isn’t American policy, and even Israeli policy now, very closely aligned with Saudi Arabia and its particular view of Islam, which has been very much, very powerful, because it’s backed by money and so forth? On the other hand, you have the one that Donald Trump would like us to hate most, and Muslims the most, are the Shiites that are allied with Iran. What was your message of your book to these two groups? That they should both embrace peace and find common ground, if they really believe in Muhammad?

JC: Well, that’s certainly the case, that is to say that the Qur’an itself deplores the sectarianism of Christianity, which was rocking the known world at that time. The imperial religion in Constantinople of the Christian Roman Empire was the Chalcedonian branch of Christianity. And it had a particular definition of Jesus’ humanity and divinity and relationship to God the Father. But most people at that time in Syria and Egypt followed the Miaphysite branch of Christianity, which had a different definition of all those things. And they came to blows, and there was persecution and bloodshed over these doctrinal pronouncements. And so the Qur’an castigates the Christians for being so sectarian, and warns the Muslims not to fall into sectarianism. And within years of the Prophet’s death in 632, schisms started growing up in Islam. And as you say, one of the most enduring and fateful was the difference between the Sunnis and the Shiites. Shiites favored the Prophet’s son-in-law and cousin Ali as the rightful vicar of the Prophet, and the Sunnis believed in a series of communally chosen leaders, which included Ali, but not exclusively. And over these sorts of things, sectarian divisions emerged that still define relationships between the two. But the thing I would like to underline is that sectarian identity is not fate, and there have been large periods of time in which Sunnis and Shiites did not make their sectarian identity a basis for communal violence. In fact, if you go back and read Iraqi newspapers in the fifties and sixties, the big question is, are you communist or not. And you know, do you favor the peasants or the landlords. And it’s only after the Gulf War and the American invasion that power vacuums grew up where politicians could mobilize these religious identities for political purposes. But the divisions are there, and they can be used for those purposes. I think the message of the Qur’an is that they shouldn’t be; that is to say, that Muslims should attempt to pull together across these sectarian divisions.

RS: Well, let me end on that, because I brought up my own, you know, that I went to Egypt at the time of the Six-Day War, and that I was in Israel, and I was in other places. And I’ve certainly never been an expert on the region or on these religions. But when I was in Egypt at that time, despite the fact that there had been this horrible, destructive war—a very short duration, but still had done damage and so forth—I interviewed Jewish people in Cairo who seemed to live in Egypt and have a different sense of history. And I found the big argument, whether I was talking to Muslims or the few Jews I found, or Christians, was more about whether Nasser and the other colonels were corrupt, or whether they were going to be real revolutionaries, or whether they were going to distribute wealth, or what they were going to do about the water. And I just want to end, really, on sort of what is the value of scholarship, let alone journalism? Because I mean, it seems to me what you’re dedicated to in your book on Muhammad is really answering the question, what do we know about the origins of this religion? What do we know about its content? What are the implications, are people misusing it, what can be said? Basically, the opposite of demonization; basically, understanding and enlightenment. And I just wonder, what’s your report card on how we think about Muhammad and Muslims?

JC: Well, I think it’s certainly the case that the rise of Israel, and the Arab-Israeli conflict, has had an unfortunate effect on relationships between Jews and Muslims. Not always and everywhere, but often. And that one of the things that I find in the book is that the Qur’an is remarkably pro-Jewish. It talks about Jews, frankly, as God’s chosen people; it defends synagogues from attack. And towards the end of the book, it says that Muslims may intermarry with Jews and Christians, and may have communal meals with them. So you know sociologists define ethnicity as having to do with who you will marry and who you won’t; people with a particular ethnicity only marry into that ethnicity. But the Qur’an is creating kind of an ethnicity of Abrahamians, of people who follow the one God, and includes Jews. And in Roman law of that time, Jews could not marry Christians, and indeed were they to do so it was a death penalty. So the Qur’an has this enormously enlightened view of the relationship between the monotheistic religions, and has a warm embrace of many aspects of Judaism, of the Bible; it says that there’s light and guidance in it. There does seem to have been some conflict at some points with some Jews and some Muslims, but that’s not made a matter of principle in the book. So I wish people could get past the geopolitics, which after all is ever-changing, and go towards principle. And the principle that the Qur’an is teaching is an ecumenical one, including towards Jews. And I think there is that ecumenical sense in much of the Bible, if you think about Isaiah and his hopes for peace, and for the lion and the lamb–which Jesus also quoted. That there’s much value in these scriptures if you want to think about getting along.

RS: I don’t want to simplify this, but I got the feeling—you describe the caravans, you describe trade, you describe the necessity of trade. That if you don’t get food from where it can be grown to where people need it, and so forth, life is not sustained. So one actually gets from this a sense that some notion of order and tolerance and peace is required for survival. And if you can’t maintain that, everything is going to go haywire. Here, you know, is young Muhammad, actually being judged by how effectively he can escort a caravan, right? And so the test for him, really, is can he negotiate through hostile communities; can he get along with people who are of different religion or different ethnicity or different this or different that—and somehow still exchange what he’s brought to what is needed, that trade. And when people look at this world, we think well, why can’t we all just do that? Why can’t we all just get along? Why can’t we do that? And then the question, really, about religion—is religion, to what degree is it an obstacle to doing that and dividing people and creating hatred, and to what degree does religion show a way of getting along with some common purpose of survival and living a good life, and maybe getting to the reward of some kind of afterlife or judgment? Maybe the problem with the Muslim religion is we’re afraid that some people believe in it when we don’t, most of us don’t believe in any religion.

JC: Well, I think that can certainly be the case in societies like the Netherlands, which are really post-religious, and where Protestants and Roman Catholics and Jews mostly don’t practice anymore, but have a sense of broad tolerance among their ethnic religious communities. The arrival of Moroccans and Turks who actually still practice Islam, I think, is a little bit of a challenge to that system of tolerance, which also kind of depends on people being post-religious. But I think that you put your finger on it, that because of where and when the Qur’an emerged, and the early Islam emerged, you know, it was a violent society all around them, these Roman-Iranian wars and the tribal raiding. And the people who spoke Arabic in western Arabia had attempted to deal with this by declaring some months to be months of peace, where you couldn’t raid, you couldn’t fight, and declaring some places like Mecca to be sanctuaries, where it was a zone of peace and worship. And they, I think they used that, the Arab traders, to make an argument to the tribes that they ought not to attack during those times and places. And in a way, I would argue that what Muhammad wished for was to expand that zone of peace that he conceived in Mecca, to encompass the whole world.

RS: Well, that’s a powerful message. And my hat’s off to Juan Cole, professor at the University of Michigan, great scholar, for reminding us of the richness, the variety within the Muslim religion, its long history, and why there’s a very, very large group of people in the world, maybe most of the people who really still care and have religion, believe in that faith. So, thanks for doing this.

JC: Thanks so much, Bob.

RS: Well, that’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. Our engineers at KCRW are Mario Diaz and Kat Yore. Our producers are Isabel Carreon and Joshua Scheer. And see you next week.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.