This Is As Good As It Gets?

The despair of lower-income voters was seen as a political problem rather than an empirical reality. President Joe Biden, with his fingers crossed, speaks to reporters after being asked a question about a Gaza ceasefire on Nov. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

President Joe Biden, with his fingers crossed, speaks to reporters after being asked a question about a Gaza ceasefire on Nov. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

“The U.S. economy is currently near perfect.” So wrote the economist Jennifer Harris — “the quiet intellectual force behind the Biden administration’s economic policies,” according to the New York Times — in a post on X in mid-July. The post has since been deleted, but Harris’ view was hardly idiosyncratic at the time. In the months before Donald Trump’s victory, not just elected Democrats but countless wonks and columnists were celebrating the Biden administration’s macroeconomic successes: sustained low unemployment, strong GDP growth, falling inflation and rising wages. This is the stuff of economists’ dreams — and as close to fulfilling labor’s long-held hope of full employment as the country has come in nearly half a century. Under contemporary U.S. capitalism, this is about as good as it gets.

Around the same time that Harris was celebrating the economy, a heated exchange broke out in Congress. Rep. Ann Wagner, R-Mo., berated Secretary of State Antony Blinken for the delayed sales of weapons to Israel that “just happen to be made in the St. Louis metropolitan area, in St. Charles, in my district.” She scolded Blinken: “My constituents … rely on these jobs to pay for their mortgages, their car payments, their day care costs, and they can’t afford to lose their jobs to support this partisan stall tactic.” In response, Blinken seemed flustered but, for once, honest enough: He insisted that there were no intentional delays; Israel would be armed, as it wished; St. Charles would have jobs, as it should; Palestinians would die, as they seemingly must. This encounter prompts a question: How could the economy be “near perfect” if U.S. military largesse was the only thing saving an entire congressional district from immiseration?

“Credit card delinquencies for the youngest households have risen sharply.”

On Nov. 5, the American electorate offered one kind of answer. A majority voted for Trump, and cited the economy and immigration as deciding factors. The puzzle, from the vantage of Joe Biden’s advisers and allies like Harris, is why. The topline economic indicators are no mirages, nor should their implications for workers’ lives be dismissed. No other developed country has emerged from the pandemic with a better record of GDP growth, inflation and employment than the U.S. Workers continued to get laid off and fired, but the hell of prolonged unemployment has been largely avoided. All this is nothing to scoff at. The problem is that it’s only part of the story.

For some professional observers — those tasked with making money rather than policy — there were signs of trouble all along. In June, analysts with the asset management firm Apollo published a mid-year outlook report ominously titled “An Unstable Economic Equilibrium.” They acknowledged the “stamina,” “resilience” and “underlying strength” of the American economy, which showed no signs of recession, despite doomsayers’ prognoses. For two years, the Federal Reserve had managed to hike interest rates without tanking the job market — the famous “soft landing.” Then, in December 2023, Fed committee members signaled that rate cuts were coming, breathing new life into financial markets: “bond issuance surged, [mergers and acquisitions] activity awakened, risky assets rallied,” the report reads. For the investor class, these were heady times.

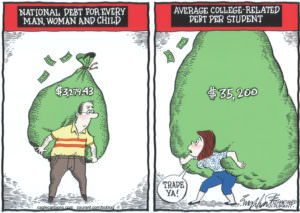

But under the frothy surface, trouble was stirring. “Credit card delinquencies for the youngest households have risen sharply,” notes the Apollo report, “and are approaching rates last seen during the Global Financial Crisis.” Likewise, “people in their 30s and below are falling behind on their auto loans at a faster pace than during the pandemic,” nearing rates “almost as bad as … at the peak in 2008.” Even when not crushed by debt, workers simply have less money. Those making less than $45,000 a year hold less in savings and checking accounts than they did before the pandemic; middle-income households are faring only marginally better. For all the media talk of real hourly wage growth, political scientist Thomas Ferguson and economist Servaas Storm have found that the lowest-paid workers had suffered a “cumulative loss in real average weekly earnings” of 2.5 percent as of March. Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Cost Index, they tracked real wage growth for major private industries from 2019 through the beginning of 2024 and found declines nearly everywhere, with exceptions in retail trade and leisure and hospitality. The Fed’s serial interest rate hikes might not have spurred mass unemployment, but they helped crush low-wage workers nonetheless.

Elite consumption is so lopsided that it appears to be driving much of the economy, while the rest barely hang on.

For those focused on short-term macroeconomic indicators like growth and unemployment, that immiseration has been hard to see — and voters’ cries of misery beggared belief. How could so many people be drowning when GDP growth was so robust and unemployment so low? The Apollo report was clear-eyed. The post-pandemic recovery was “a story of two cohorts.” One group owes money and has been crushed by high interest rates; the other owns assets and has never been better off financially. For the latter, inflation was a nuisance at worst; it was hard to believe anything was fundamentally wrong. But as the Financial Times noted on the eve of the election, “the bottom 40 percent by income now account for 20 percent of all spending while the richest 20 percent account for 40 percent”—“the widest gap on record.” Elite consumption is so lopsided that it appears to be driving much of the economy, while the rest barely hang on.

The much-touted wage gains received by the bottom decile of earners appear to be only the bare minimum needed, as the cost of rent and food exploded, by more than 17 percent and 19 percent respectively from 2020 to 2023. Furthermore, even as hourly wages rose from 2021 into 2024, average weekly working hours declined. In a sense, workers are being paid more but taking home less: comparing between 2017-2019 and 2021-2024, Ferguson and Storm found average real weekly earnings fell across all wage classes, with disproportionate declines in the median, the third quartile, and the ninth decile of earners. These, of course, are the very income bands in which Trump made inroads in 2024.

Still other crises were hiding in plain sight. After the rollback of pandemic-era welfare measures — from expanded child tax credit, Medicaid, SNAP and unemployment insurance benefits to eviction moratoriums — rates of homelessness and child poverty predictably resurged. Yet since this was in effect simply a return to the pre-Covid norm, it seems to have barely registered at the highest levels of the Democratic Party. The despair of lower- and middle-income voters was seen as a political problem rather than an empirical reality, an irrational and irritating sideshow to an otherwise “near perfect” economy. Ideologically on its deathbed, neoliberalism lives on in practice, shaping social life and configuring the boundaries of political economy.

* * *

Given all this, a plausible case can be made that any incumbent would have lost to any challenger, almost regardless of strategy, messaging or platform. As many commentators have noted, in the past year incumbent parties around the world — including in Argentina, France and India — have suffered political defeats attributable to the pain of inflation. One notable exception to this trend, however, is Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist and leftist Jewish woman who won over a deeply Catholic, oil-producing and still profoundly patriarchal country hit by an even worse bout of inflation than the U.S. Her triumph shows that the substance of politics actually matters: the impressionistic abstractions of comparative social science should offer little comfort to American liberals. Incumbents aren’t interchangeable variables, but rather actors that create particular kinds of social politics as much as they are created by them.

But Biden’s incumbency, embraced happily by the Kamala Harris campaign, created no durable politics. Trump’s first presidency clearly did. Yet it is notable how indecisive Trump’s recent victory was: he secured fewer votes than Biden did in 2020 and is on track to win the popular vote by a slimmer margin than Clinton in 2016. This is no credit to the Democratic Party, but rather a reminder of how repellent Trump rightly remains to so many people. As in 2016, no faction appears capable of achieving hegemony. Nevertheless, Trump is undeniably the more consequential figure, forcing a bipartisan about-face on trade and a revival of anti-immigrant fervor. This has made the shift toward Trump among fractions of the traditional Democratic base, especially Latino voters, all the more confounding.

Joe Biden’s incumbency, embraced happily by the Kamala Harris campaign, created no durable politics.

So far, this nascent electoral formation has provoked more clichés than analysis. Those that attribute the rightward shift of Latino men to their essential conservatism have no convincing answer for what occurred just across the border in Mexico. And those that take the same shift as proof of the irrelevance of racism in the Republican coalition betray either naivete or cynicism. The pat academic slogan that “Latinos are not a monolith” likewise says nothing useful about Latinos or the social worlds they inhabit. You’d learn more from standing on any corner near Mexico City’s Zocalo and observing who can patronize brand-name stores and who is forced to sell fruit and flowers on the streets — or from asking any affluent Puerto Rican what they think about Haitians. Racist assumptions of social hierarchy among immigrants or their U.S.-born children don’t disappear simply because the American commentariat doesn’t see them. Cesar Chavez opposed undocumented immigration, as did the League of United Latin American Citizens. Race holds no permanent guarantees of virtue or vice, for it is historically and ideologically constituted precisely to justify evolving social hierarchies.

But more significant, for Latinos as for most voters, was the profound social unmooring wrought by the cost-of-living crisis. The GOP capture of 12 out of 14 heavily Latino counties along the Texas-Mexico border was unprecedented in recent U.S. political history. Fabiola Rodriguez, a young single mother in the region, told the New York Times that she doesn’t take her “children to the grocery store because I know I won’t be able to afford what they want.” Another formerly reliably Democratic voter complained that “Democrats are saying the economy is really strong. But really, the metrics are not there to reflect what people are feeling.” Conservatives have pounced. Gary Groves, a lifelong Republican from the region interviewed by the Times, was eager to show constituents a video “in which a woman complained that her husband, a Latino immigrant who had recently become a citizen, could no longer get a construction job because local contractors were hiring only unauthorized migrants, who generally worked at lower wages.” Another local Republican cynically said that they “were talking about prosperity and hope while the Democrat Party was talking about pronouns.”

A mother’s fear of embarrassment in front of her children; a husband’s fear of losing his livelihood and, with it, his manhood. As Melinda Cooper explained of the 1970s, inflation is often read as an index of moral disorder as much as it is an index of economic disorder. And as with the 1970s effort to restore capital’s value, today’s fight over restoring the dollar’s value is expressed simultaneously as a restoration of conservative family values.

The left must not be cowed into a narrow politics of income inequality and redistribution; it must look further, toward democratic control of capital itself.

By themselves, strong growth and low unemployment cannot wash away social divisions, any more than they can empower labor enough to substantively increase wages, to say nothing of raising the labor share of national income. The left must not be cowed into a narrow politics of income inequality and redistribution; it must look further, toward democratic control of capital itself. But doing so means forging a broad and deep culture of solidarity, something that in turn cannot be done by waving away the problems of racism, misogyny, xenophobia and transphobia in favor of simple economic populism. The question haunting the latter is always: Who makes up the populace in populism? Perhaps nothing illustrates the problem with this approach more than the right’s anti-immigrant economic nationalism and liberal acquiescence to it. Immigration is seen unfavorably by most voters today, even as low unemployment has eased competition for jobs. But this is a politically contingent fact, not a law of nature. As recently as 2020, Gallup reported that more Americans wanted an increase in the number of immigrants to the country than wanted a decrease. The Democratic Party squandered the opportunity to build a politics from that moment, but this does not mean that defeat is permanent.

One can look to the recent history of immigrant worker organizing for a glimpse of what might be possible. One of the few bright spots amid the long decline of organized labor was the SEIU’s remarkable Justice for Janitors campaign in California in the 1990s. At the time, custodial services in the state had been hollowed out by subcontracting, producing unlivable wages and appalling work conditions, particularly for women, who faced the threat of sexual harassment and assault. California was also fertile ground for nativism: in 1991, a year after the launch of the Los Angeles Justice for Janitors strike, Republican Gov. Pete Wilson won election with a rabidly anti-immigrant campaign that promised to bar undocumented immigrants from public schools, hospitals and other social services. Yet despite their daunting vulnerabilities, undocumented janitors worked alongside resident and citizen workers to organize, march and eventually win both a union and a dramatic pay raise. This was not just a case of people “realizing their interests,” but instead a reconstitution of the very core of who “the people” were, and how they thought of and related to one another.

* * *

Maladies such as racism, misogyny, nativism or transphobia cannot be treated as static impediments, best ignored for the sake of “real” class interests. A broader class politics is, in fact, impossible to forge without confronting those malignant forces: Where there is a workplace, there are women underpaid in their jobs, Black people denied interviews, trans people humiliated and facing homelessness, weary immigrants fearing deportation. These are comrades, not inconveniences.

The left must come to terms with how people understand their own turmoil and work to mobilize them on different ideological terrain. That means pressing on the countless contradictions that riddle the right’s fragile coalition: Elon Musk’s neo-Chilean dreams of making the U.S. economy scream with trillion-dollar federal budget cuts and the deep precarity already felt by the working class; the bipartisan commitment to Israel’s genocidal campaign, and the social desire to end needless wars; the desperation for cheaper food and the dreams of ethnically cleansing the exploited hands that bring it to you; the fear and distaste for immigrants, knowing that you were once one too. The left can’t mock or wish away these contradictions while shouting for more “bread and butter.” We must face them directly if we are to find the political opportunity and strategic leverage needed to overcome them.

The task will not be easy. These are grim times — enough to compel some to reach for the 1850s or 1930s or Jim Crow as analogies to describe our moment and lend it moral gravity. In their crudest form, these comparisons substitute history for moralizing time travel. Their appeal is plain, not only in their comforting conclusions — slavery liquidated, Nazis vanquished, Jim Crow dismantled — but for the identifications they enable: we can be abolitionists, antifascists, freedom fighters. But the past needs no pedestal; the gravity of our own moment is enough. Rebuilding the left, with or without the Democratic Party, will require us to face the problems that workers are actually confronting, rather than explaining them away — still less daydreaming about the inevitable moral goodness of a victory yet to come.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.