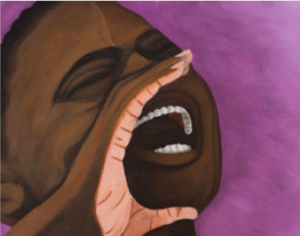

Troy Davis and the Machinery of Death

On Sept. 21 at 7 p.m., Troy Anthony Davis was scheduled to die. I was reporting live from outside Georgia's death row in Jackson, awaiting news about whether the Supreme Court would spare his life.On Sept. 21 at 7 p.m., Troy Anthony Davis was scheduled to die. I was reporting live from outside Georgia’s death row in Jackson, awaiting news about whether the Supreme Court would spare his life.

Davis was sentenced to death for the murder of off-duty Savannah police officer Mark MacPhail in 1989. Seven of the nine nonpolice witnesses later recanted or changed their testimony, some alleging police intimidation for their original false statements. One who did not recant was the man who many have named as the actual killer. No physical evidence linked Davis to the shooting.

Davis, one of more than 3,200 prisoners on death row in the U.S., had faced three prior execution dates. With each one, global awareness grew. Amnesty International took up his case, as did the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Calls for clemency came from Pope Benedict XVI, former FBI Director William Sessions and former Republican Georgia Congressman Bob Barr. The Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in granting a stay of execution in 2007, wrote that it “will not allow an execution to proceed in this state unless … there is no doubt as to the guilt of the accused.”

But it is just that doubt that has galvanized so much global outrage over this case. As we waited, the crowd swelled around the prison, with signs saying “Too Much Doubt” and “I Am Troy Davis.” Vigils were being held around the world, in places such as Iceland, England, France and Germany. Earlier in the day, prison authorities handed us a thin press kit. At 3 p.m., it said, Davis would be given a “routine physical.”

Routine? Physical? At a local church down the road, Edward DuBose, the president of Georgia’s NAACP chapter, spoke, along with human rights leaders, clergy and family members who had just left Davis. DuBose questioned the physical, “so that they could make sure he’s physically fit, so that they can strap him down, so that they could put the murder juice in his arm? Make no mistake: They call it an execution. We call it murder.”

Davis had turned down a special meal. The press kit described the standard fare Davis would be offered: “grilled cheeseburgers, oven-browned potatoes, baked beans, coleslaw, cookies and grape beverage.” It also listed the lethal cocktail that would follow: “Pentobarbital. Pancuronium bromide. Potassium chloride. Ativan (sedative).” The pentobarbital anesthetizes, the pancuronium bromide paralyzes, and the potassium chloride stops the heart. Davis refused the sedative, and the last supper.

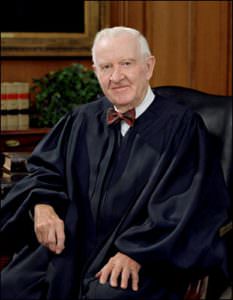

By 7 p.m., the U.S. Supreme Court was reportedly reviewing Davis’ plea for a stay. The case was referred to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who hails from Pin Point, Ga., a community founded by freed slaves that is near Savannah, where Davis had lived.

The chorus for clemency grew louder. Allen Ault, a former warden of Georgia’s death row prison who oversaw five executions there, sent a letter to Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal, co-signed by five other retired wardens or directors of state prisons. They wrote: “While most of the prisoners whose executions we participated in accepted responsibility for the crimes for which they were punished, some of us have also executed prisoners who maintained their innocence until the end. It is those cases that are most haunting to an executioner.”

The Supreme Court denied the plea. Davis’ execution began at 10:53 p.m. A prison spokesperson delivered the news to the reporters outside: time of death, 11:08 p.m.

The eyewitnesses to the execution stepped out. According to an Associated Press reporter who was there, these were Troy Davis’ final words: “I’d like to address the MacPhail family. Let you know, despite the situation you are in, I’m not the one who personally killed your son, your father, your brother. I am innocent. The incident that happened that night is not my fault. I did not have a gun. All I can ask … is that you look deeper into this case so that you really can finally see the truth. I ask my family and friends to continue to fight this fight. For those about to take my life, God have mercy on your souls. And may God bless your souls.”

The state of Georgia took Davis’ body to Atlanta for an autopsy, charging his family for the transportation. On Troy Davis’ death certificate, the cause of death is listed simply as “homicide.”

As I stood on the grounds of the prison, just after Troy Davis was executed, the Department of Corrections threatened to pull the plug on our broadcast. The show was over. I was reminded what Gandhi reportedly answered when asked what he thought of Western civilization: “I think it would be a good idea.”

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

Amy Goodman is the host of “Democracy Now!,” a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 900 stations in North America. She is the author of “Breaking the Sound Barrier,” recently released in paperback and now a New York Times best-seller.

© 2011 Amy Goodman

Distributed by King Features Syndicate

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.