Trump, Xi Jinping and the Tariffs

The collision between China’s commitment to export-driven industrialization and Trump’s fixation on protectionist tariffs was set on course four decades ago. In this 2019 photo, U.S. President Donald Trump, left, meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

In this 2019 photo, U.S. President Donald Trump, left, meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

In 2011, Donald Trump spoke before an audience of about a thousand in Las Vegas, teasing a prospective, if fanciful, presidential run. Halfway through a rant over Middle East policy and oil prices, he digressed for a moment on trade with Asia:

China, I said the other day — very, very hard to buy anything, outside of China. Certain other countries also, but China’s, you know, the one. And somebody said, “What would you do? What could you do?” So easy. I drop a 25 percent tax on China [applause]. And you know, I said to somebody that it’s really the messenger. The messenger is important. I could have one man say, [falsetto] “We’re going to tax you 25 percent.” And I could say another: “Listen, you motherfuckers, we’re going to tax you 25 percent!”

Since long before he became president, Trump has flip-flopped constantly on the standard presidential topics, from the Middle East to health care to abortion. But give him this: he has been remarkably consistent on tariffs, a centerpiece of both his domestic and foreign agenda. “This is something that has been stuck in his craw since the ’80s,” a friend and former steel executive told the New York Times. “It came from his very own core belief.”

“To me, the most beautiful word in the dictionary is ‘tariff,’” Trump declared a few weeks before the 2024 election. During his first term, Trump’s team initiated a series of major duties on Chinese imports. Starting with solar panels and washing machines, they soon extended to steel and aluminum, then nearly half of all goods from China, worth roughly $200 billion. By late 2019, the average tariff rate reached 21 percent. Trump had been true to his word.

“This is something that has been stuck in his craw since the ’80s.”

Trump’s tariffs have been panned by economists, who warn that they increase inflation and hurt farmers and middle-class households above all. But Democrats have been reluctant to undo them. The Biden administration not only maintained but expanded Chinese duties last spring, now aimed at electric vehicles, silicon chips and lithium batteries. Today, anti-China policies are a rare point of bipartisan consensus. Popular opinion on China has steadily soured since the 2000s, first among business owners, then the public. Pew polling shows that some 80 percent of Americans view the country unfavorably, a historic low. Enrollments in Mandarin courses at U.S. universities, which climbed steadily after 1978, have been falling since 2013.

Trump helped set the tone when he announced his candidacy for presidency in 2015 at Trump Tower, naming restrictions on Chinese trade as his first priority. That day he also, infamously, warned of “drugs,” “crime” and “rapists” being sent from Mexico. Trump’s current brand of racism appears to revolve around these two countries: “There are no jobs,” he declared, “because China has our jobs and Mexico has our jobs.”

Still, on revisiting that 2015 speech, there is a surprising appearance by a third country, sandwiched between China and Mexico: Japan. “When did we beat Japan at anything?” Trump railed. “They send their cars over by the millions, and what do we do? When was the last time you saw a Chevrolet in Tokyo? It doesn’t exist, folks. They beat us all the time.” Commentators at the time laughed at Trump’s Japan fixation. They called it “anachronistic,” “out-of-date” and “odd.” But Japan has in fact been foundational to Trump’s worldview, as historian Jennifer M. Miller has argued, dating back to his emergence as a national figure in the ’80s. In fact, Japan even provided the template for his views on China, which, decades later, hold massive consequences for the rest of the world.

* * *

When Trump published “The Art of the Deal” in 1987, U.S.-Japan tensions were at their height. Rising imports of Japanese durable goods, especially automobiles, had coincided with the decline of U.S. manufacturing. In the 1970s, global oil shocks had pushed American drivers to buy leaner, more efficient cars from Toyota, Honda, Mazda and Subaru. Trump promoted the book on Larry King and Oprah Winfrey, testing out lines that sound awfully similar to his 2011 Vegas speech — and his rhetoric as a politician since:

We’re a debtor nation. Something’s going to happen over the next number of years in this country, because you can’t keep on losing $200 billion … and yet we let Japan come in and dump everything right into our markets. It’s not free trade. If you ever go to Japan right now and try to sell something, forget about it, Oprah. Just forget about it. It’s almost impossible. They don’t have laws against it. They just make it impossible. They come over here, they sell their cars, their VCRs, they knock the hell out of our companies.1

Trump’s views were far from extreme at the time. In 1985, the New York Times Magazine ran a cover story by Theodore White, a prize-winning journalist who had covered the Pacific War, titled “The Danger from Japan.” Accompanying it was an ominous full-page photograph of a Nissan sedan being unloaded at a port in Elizabeth, New Jersey. White wrote,

Today, 40 years after the end of World War II, the Japanese are on the move again in one of history’s most brilliant commercial offensives, as they go about dismantling American industry. Whether they are still only smart, or have finally learned to be wiser than we, will be tested in the next 10 years. Only then will we know who finally won the war 50 years before.

A few months later, the U.S. hosted a summit of European, American and Japanese finance officials at New York’s famed Plaza Hotel (which Trump would purchase in 1988). The resulting Plaza Accords came amid a flurry of bilateral deals meant to “voluntarily” reduce Japanese exports while opening Japan’s market to the world’s goods, thereby driving up domestic consumption — much like American prescriptions for China today. Under pressure from the G5, Japan’s finance ministry lowered interest rates and banks greenlit construction projects. The easy money, combined with fewer exports, pushed Japanese businesses into speculative real estate.

At the height of the ensuing bubble, a square foot in Tokyo could sell for up to 350 times as much as one in Manhattan. The Imperial Palace was nominally worth as much as all of California. From 1987 to 1994, the two richest people in the world, according to Fortune, were property magnates Tsutsumi Yoshiaki and Mori Taikichirō. And in 1989, Mitsubishi Estates purchased Rockefeller Center. That same year, when Trump was asked by a reporter about his net worth, he replied, “Who the F knows? I mean, really, who knows how much the Japs will pay for Manhattan property these days?”

If Trump was getting a bad deal, then so was the entire nation.

Since the ’80s, Trump has never made much distinction between his personal business experience with incipient globalization and his policy prescriptions. If Trump was getting a bad deal, then so was the entire nation. In a 2018 interview with the Wall Street Journal, he recalled the origins of his trade platform: “I just hate to see our country taken advantage of. I would see cars, you know, pour in from Japan by the millions.” As the center of Asian economic dynamism has shifted to China, so has the target of Trump’s ire. “Very, very hard to buy anything,” Trump said in his Vegas speech, “outside of” Chinese goods. When he tried to purchase American-made glass and furniture for his properties, he found only Chinese factories. Before 2016, Trump had never visited China, but he had sent his children there to secure licenses for his brand or to negotiate real estate deals, only to be stymied each time.

In 1982, at the peak of the Japan panic, two white Chrysler employees, one recently fired, confronted and killed a Chinese American named Vincent Chin in Highland Park, Michigan, the birthplace of Henry Ford. The episode symbolized, not for the first time, the fungible threat of Chinese, Japanese and otherwise exotic Asian capital in American minds. Trump’s pivot to China has only demonstrated it more bluntly. As he told a reporter during his first term, he saw Japan as “interchangeable with China, interchangeable with other countries. But it’s all the same thing.” His embrace of tariffs has likewise been a constant, even as their target has shifted. “Where are my tariffs?” Trump declared in meetings with advisers early during his presidency. “Bring me my tariffs.”

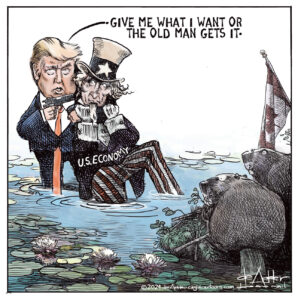

In his second term, Trump has only widened the tariff net to include neighbors and ostensible allies Canada and Mexico. Both countries, Trump insists, will be subject to a 25 percent tariff unless they halt flows of migrants and opioids across their borders with the U.S. Meantime, in his first week in office, Trump threatened tariffs of up to 50 percent against Colombia after two airplanes with repatriated Colombians were blocked from landing; he has brandished similar threats against Denmark in a harebrained push to purchase Greenland. Who knows how real these threats are? In December, Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., a Trump surrogate, tried to reassure an audience of jittery CEOs that they were merely “an effective negotiating tactic.” Tariffs against China, on the other hand — “that’s a horse of a different color.”

* * *

In 2012, not long after Trump’s rant in Vegas, the Chinese Communist Party selected a new leader, 59-year-old Politburo member Xi Jinping. In histories of the current trade war, Xi will no doubt be remembered as Trump’s counterpart in nationalist escalation. But in the early years of his rise, U.S. observers were cautiously hopeful that he would be a reformer, receptive to American-style liberalism. The Wall Street Journal reported that in 1985, as a party official in Hebei province, Xi Jinping had stayed with a family in Muscatine, Iowa, on a tour of corn production techniques. His daughter was attending Harvard. He liked Hollywood movies. And he had met Magic Johnson and David Beckham.

Journalists also leaned on what they know about his father, Xi Zhongxun. The elder Xi had joined the party in the 1920s, rising to high-ranking positions by the 1950s and claimed revolutionary status to the end of his life. He was also purged during the Cultural Revolution, with severe consequences for his young son. In 1978, Xi Zhongxun was rehabilitated by the newly ascendant Deng Xiaoping: a leaked U.S. intelligence cable reported that he was “actually closer to Deng than to Mao.” When he was appointed party secretary of Guangdong, Xi Zhongxun’s first task was to mobilize capital from Hong Kong, then still a British colony, “northwards” into the southern province. He helped establish the first experimental “special economic zones” along China’s coasts, including the crown jewel of the SEZs, Shenzhen.

Xi Zhongxun was aligned with the two reformers, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, who spearheaded political and economic liberalization in the 1980s. At the end of the decade, when Hu and Zhao were attacked by party hardliners — culminating in the violent Tiananmen crackdown — he defended them privately. No wonder U.S. observers hoped Xi Jinping would follow in his father’s footsteps. As one veteran American businessman put it: “We all hope the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

Economically, Xi’s arc can indeed be seen as a continuation of his father’s final legacy.

On the political front, Xi Jinping has disappointed liberals. He has restricted political expression, spearheaded the repression of Xinjiang, and reasserted state control over the economy and much of everyday life. Yet on the economic front, Xi’s arc can indeed be seen as a continuation of his father’s final legacy. Returning from his trip to Iowa in 1985, Xi Jinping became deputy mayor of Xiamen, Fujian, the SEZ with the closest ties to Taiwan and Taiwanese capital. He moved to the eastern province of Zhejiang in 2002 before being appointed as Shanghai party secretary in 2007. He was credited with helping U.S. companies establish a foothold in China, including FedEx, Citibank and McDonald’s. From the ’80s to the 2000s, Hong Kong and Taiwan were the top two sources of foreign investment in China, totaling hundreds of billions of dollars. Looking back in 2018, Xi Jinping declared that China’s rise to the world’s second-largest economy “has to be chalked up to our Taiwan compatriots and Taiwan companies.”

Like that of Trump, seven years his elder, Xi Jinping’s economic worldview can be traced to formative experiences in the 1980s. Both men’s political careers were shaped by the rapid global ascent of Japan and the Asia-Pacific region. For Xi, it was the party’s turn toward the regional model of exporting consumer goods across the Pacific. In coastal cities like Shenzhen and Xiamen, officials positioned themselves as successors to the postwar cycle of Asian “miracles,” most directly by way of Hong Kong and Taiwan, but always anchored in the pioneering experience of Japan. For Trump, meanwhile, Japan represented a formative encounter with threatening foreign capital, a national trade deficit and the decline of American industry. He presciently seized on a national backlash against a postwar Asia-Pacific alliance that had morphed from a provisional security arrangement into an economic monster.

* * *

In 1987, before his appearance on Oprah, Trump placed an ad in the country’s major papers that railed against U.S. security guarantees and military aid to allies such as Saudi Arabia and Japan:

Over the years, the Japanese, unimpeded by the huge costs of defending themselves (as long as the United States will do it for free), have built a strong and vibrant economy with unprecedented surpluses. They have brilliantly managed to maintain a weak yen against a strong dollar. This, coupled with our monumental spending for their, and others, defense, has moved Japan to the forefront of world economies.

The U.S. occupation of Japan began immediately after its 1945 surrender. Early on, Gen. Douglas MacArthur imposed a series of New Deal-style policies, supporting labor unions and women’s rights while dismantling the imperial war machine and the gigantic holding companies that had powered it. However, starting in 1947, State Department officials intervened and reoriented U.S.-Japan policy toward a military and economic strategy of Communist containment.

What historians call the “reverse course” was not made out of consideration for the Japanese people, whom many U.S. officials still hated for Pearl Harbor, and against whom they had unleashed such awesome violence. (President Harry Truman called the Japanese “vicious and cruel savages.”) The priority was regional strategy. Initially, officials proposed exporting U.S. raw goods to Japan, lowering barriers to imports, and encouraging Japan to bolster a perimeter of anti-Communist influence stretching “from Hokkaido to Sumatra” — or, as Secretary of State Dean Acheson put it in 1950, a “defensive perimeter” from the Aleutians to the Philippines.

By the 1950s, the U.S. and Japan had built a regional anti-Communist alliance.

The Korean War brought this vision closer to reality. The U.S. permanently expanded its military presence in Korea, Taiwan and Japan, aided by “special procurement” orders for Japanese metals, textiles, vehicles and machinery. The spending jumpstarted Japan’s dormant industries and revived them to wartime levels; Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru called them a “gift of the gods.” Yoshida also pushed the U.S. to assume Japan’s military responsibilities — as Trump would later complain — freeing up the country for single-minded pursuit of economic growth. By the 1950s, the U.S. and Japan had built a regional anti-Communist alliance, largely along the contours of the imperial Co-Prosperity Sphere vanquished just a few years earlier. John Emmerson, an American diplomat who arrived in Tokyo in 1945, recalled taking over an office building formerly occupied by Mitsui executives. On his way out, one employee “pointed to a map on the wall depicting Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere. ‘There it is,’ he said smiling. ‘We tried. See what you can do with it!’”

In the original vision, Japan’s industrial growth was a means to an end, subordinated to American security. Starting in the 1960s, however, the capitalist Asia-Pacific grew into something different altogether. From 1965 until 1990, it was by far the fastest-growing economic region in the world, led by Japan; the four “small tigers” of South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan; and the southeastern “newly industrializing economies” of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. For its champions, the newly christened Pacific Rim was an “international capitalist utopia.” But whether it appeared as “miracle” or “menace,” political scientist Meredith Woo argued, the orientalism of the time overlooked the harsh realities of the region’s military-economic dependence on the U.S. Japan could never become “number one” (as sociologist Ezra Vogel famously predicted in a bestselling 1979 book), but was consigned, Woo wrote, to “continue to play second fiddle.” No wonder Japan, when pressed at the Plaza Hotel to curb its exports, had little leverage to resist. Today China so scares Washington not only because of its uncanny resemblance to the Japanese miracle, but also for its key geopolitical differences: there will be no Chinese Plaza Accords.

* * *

If Trump’s China tariffs are now a bipartisan position, their intellectual backbone comes from Michael Pettis, an American finance professor at Peking University who has influenced both the Trump and Biden administrations. The root of the China problem, Pettis alleges, is the country’s excess savings, low consumption and industrial “overcapacity,” externalized into exports that are “dumped” onto the rest of the world. To U.S. observers, it is obvious that China should pivot from exporting goods to developing its home market — just as Japan did in the ’80s. The Communist Party’s intransigence can only result from aberrant psychology. Paul Krugman described Xi Jinping as “bizarrely unable” and “bizarrely unwilling” to shift accordingly. In the Wall Street Journal, Lingling Wei blamed Xi’s “deep-rooted philosophical objections to Western-style consumption-driven growth,” which he views as “wasteful,” “welfarism” and simply at odds with China’s ambitions for global power.

Pettis, however, does not see China’s strategy as bizarre. He notes that moving away from export-driven growth is risky. Any measures to “reverse” the ongoing transfer of wealth from households to government, by redirecting it to wages and welfare, would come with trade-offs. China’s manufacturing would suffer greatly in the short term, creating a “painful” economic contraction without any guaranteed payoff in the long term.

Rather than psychology, then, explanations for Chinese political strategy can be found in recent history. Foremost are the lessons of Japan and East Asia, in both their successes and limitations. As Chinese reformers embraced export-led industrialization in the ’80s, they reasoned that because the country was still a closed circuit, efforts to promote domestic consumption — through higher wages and social welfare programs — would come at the cost of industrial investment. Planners realized they could instead follow the model of their East Asian neighbors by using the markets of the U.S. and other rich countries to subsidize their own growth.

In 1990, heterodox economist Alice Amsden clarified the stakes of the East Asia experience. Asia’s economies, she argued, had broken with the U.S. model of mass production and mass consumption, that is, Fordism. Instead, for “late developers” like those of East Asia, the problem was

not that of too little effective demand but of too much, as different income groups and social classes struggle over the distribution of a puny pie. … What [governments] must raise is more foreign exchange, savings and public revenues; for these, and not effective demand, are the constraints on increasing the pie’s absolute size.

Chinese economic thinking has largely adhered to these principles, including a long-standing fear of domestic inflation alongside the long-standing belief that, rather than redistribution and balance, the key is to grow “the pie” — and the pie grows when technology improves. Today, China prioritizes innovation under the title of “high-quality productive forces,” entailing clean technology, electric vehicles, semiconductors and artificial intelligence — targets of the Biden tariffs — that rely as much as possible on domestic supply chains. The strategy claimed a major victory this week, when the Chinese startup DeepSeek shocked the world with an AI model that outperformed OpenAI and Meta’s models but at a fraction of the cost (the announcement also cost the U.S.’s five major tech stocks about $750 billion in market value). China’s government is aware that moving further into capital-intensive industries means cutting bait on cheaper, labor-intensive ones such as clothes and toys. Still, Xi has emphasized to officials that the economy must first “establish the new before breaking the old.”

At the same time, Xi’s China is wary of the threat of “Japanification.” The credit bubble that helped drive Japan’s runaway growth in the ’80s, and which so irked Trump, finally popped in 1990, and Japan’s own foreign investment contributed to the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Today, Japan is in the midst of its fourth “lost decade” of sluggish growth and population decline. This is the specter now hanging over China, which for all its impressive performance, remains nowhere near as rich per capita as ’90s Japan.

The 1997 crisis largely spared China, which was not yet enmeshed in regional and global capital flows. But that would soon change. By 2001, the U.S. helped shepherd China into the World Trade Organization, legitimating its place in the new, unipolar world order. That push was led by the “Shanghai faction” of Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji, against doubts from local and rural leaders. Soon, Chinese firms were accumulating a trade surplus with the U.S. Once again following Japan’s path, the People’s Bank of China began to buy up U.S. treasury bills, at times accumulating up to $1.3 trillion during the 2010s. The strategy was to keep down the value of the renminbi, suppressing prices and wages and ensuring the competitiveness of Chinese goods globally. Chinese credit also became a lifeline to U.S. consumers, who, despite stagnant real wages, continued to buy Chinese goods.

Xi’s China is wary of the threat of “Japanification.”

The 2000s were a golden age of US-China integration, an optimism symbolized by the extravagant 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, which were overseen by an ascendant Xi Jinping. Still, these years also saw signs of discontent toward globalization, even before Xi’s and Trump’s rise to power. In the U.S., labor unions had opposed China’s entry into the WTO, marching in protest during the 1999 Seattle meetings. Economists estimate the U.S. lost about 2 million manufacturing jobs in the first years after the “China Shock.” Meanwhile, fearing competition from U.S. firms, China’s provincial leaders used interventionist measures to bolster local industries, technically breaking the rules of the WTO.

As early as 2007, Chinese policymakers, wary of stoking international tensions, began talking about “rebalancing” toward domestic consumption. Efforts were expedited after the 2008 U.S. subprime mortgage crisis, when, like the U.S., the Chinese government rushed a bailout package, worth about 4 trillion RMB, or nearly $600 billion. Here China followed the path of Japan once more, as loose money led to a real estate bubble. From 2011 to 2021, about a quarter of the nation’s GDP comprised transactions in property construction, absorbing roughly half the country’s savings.

The bubble burst during the first year of the pandemic. Sensing danger, Beijing announced the “three red lines” policy, under which, in order to access more credit, companies must control their ratio of debt to cash, equity and assets. Crossing all three thresholds was the Evergrande Group, the world’s highest-valued developer. At its peak the company was worth over $40 billion, but with liabilities of more than over $270 billion. It was also a former business partner of Trump, with failed plans to build a massive skyscraper in Guangzhou. Cut off from government support, Evergrande collapsed in the fall of 2021 and was ordered last year to liquidate.

China has thus already been burned by pivoting too hastily to domestic consumption, only to be rewarded with a crisis that has saddled the country with trillions of dollars in losses. Many fear China is already in the same trap of overleveraged paralysis (“balance sheet recession”) as its neighbors. If anything, it is precisely because of the catastrophe of pro-consumption policy that Xi has turned back to the classic East Asia model. Both he and Trump are doubling down on the decades-old political views that first gave rise to the Asia-Pacific trade wars. Neither appears likely to change course soon.

* * *

A major throughline in this saga has been the automobile industry. In the ’80s, Trump took his cues from Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca, who had publicly attacked Japanese industries. (The two went on to become business partners after Iacocca purchased a condo in Trump Plaza.) These days, the new threat is Chinese electric vehicles. Last year, China’s industry leader, BYD (short for Build Your Dream), surpassed Tesla as the world’s top EV seller; the company is making rapid inroads in the European market, but has been banned from the U.S. Meanwhile, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has become the new Iacocca in Trump’s inner circle and has the president’s ear — at least for now. On an earnings call with analysts last January, Musk was already warning that BYD’s technology was “extremely good,” and that without “trade barriers” in place, the automaker would “pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world.” To Musk’s delight, Trump has since vowed even higher tariffs on Chinese EVs than those put in place under Biden.

The global car industry’s evolution is really a microcosm of changes in the past century of capitalism, whether in Michigan, Aichi or Guangdong. Car-making combines deep technical knowledge of chemical, electronic, metallurgical and logistical processes. Though a capital-intensive industry, it shares unusually intimate connections with civil society, as both a major source of employment and of final goods that shape consumers’ daily lives. Even today, new developments in car making, and in the kinds of society it produces, are a variant of Henry Ford’s original century-old vision.

But Fordism’s legacy is complicated. For Ford himself, the meaning of the system lay in controlling every aspect of production, including acquiring and recycling raw materials such as coal, iron, gas and scrap metals. “The greatest development of all,” Ford wrote, “is the River Rouge plant,” a massive complex built near his childhood home in Dearborn, Michigan, complete with its own shipyards, rail lines, power stations and blast furnaces. Ford’s obsessiveness led him to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where he felled timber, and even the Brazilian Amazon, in pursuit of rubber. “Fordlandia” failed spectacularly in the harsh tropical climate and was abandoned by 1945. Still, for businesses around the world, Fordism symbolized the awesome powers of standardization and vertical integration.

Within the tradition of social theory, however, Fordism’s significance lay in its high wages, famously $5 per day starting in 1914 (equivalent to about $20 per hour today). Rather than class beneficence, Italian politician and writer Antonio Gramsci argued, Fordist wages were part of a system of labor discipline and a means to reduce worker turnover, thereby boosting profits. They had the added benefit of aiding mass consumption — even Ford workers, it was said, could afford Ford cars — dovetailing with the emergent Keynesian dictum that boosting effective demand would soften the inequalities of industrial capitalism and keep the whole machine chugging along.

Chinese exports may suffer setbacks, but they are not disappearing from the global market anytime soon.

By the 1970s, capitalist East Asia had presented a challenge to this Fordist-Keynesian orthodoxy of mass consumption. Today, China draws the ire of mainstream economists for much the same reason. Curiously, however, China’s comparative advantage also marks a kind of return to Ford’s prized vertical integration. The sprawling integrated factory went out of style starting in the ’70s, outwitted by Japan’s “Toyota system” and its lean, just-in-time supply chains. Yet today China boasts the world’s best-integrated production systems, reinforced by recent mandates to “indigenize” and insulate value chains from foreign tariffs. BYD was founded in 1995 in Shenzhen, Xi Zhongxun’s old stomping grounds. The company first made lithium-ion batteries for smart phones before venturing into EVs. Its expertise in making low-cost, highly efficient batteries, as well as silicon chips, distinguishes it from Tesla, which purchases parts from suppliers. (In a curious historical coincidence, or farce, BYD also recently expanded to the Amazon, only to be expelled — this time not by diseases and insects but by local officials, who discovered slavery-like conditions on its construction sites.)

While China is nearing the end of its national miracle, then, its latest industries have just begun the initial stages of their product lifecycles — a historical mishmash of early and late. (BYD’s vertical manufacturing may soon cede ground to leaner rivals, as its technical monopoly evaporates.) The uncanny parallels with the experiences of the U.S. and Japan can deflate sensationalist claims about the unprecedented specter of China. Still, 2025 is not 1985, and recognizing these underlying cycles should only make us more vigilant in discerning old from new, form from content, and viewing the present with greater precision.

What is becoming clear today is that Chinese exports may suffer setbacks, but they are not disappearing from the global market anytime soon. The U.S. has already begun to import less from China relative to Mexico, Taiwan, Malaysia, India, South Korea and Vietnam. But this trend reflects, in part, the migration of Chinese capital to get around U.S. tariffs. In 2023, the Taiwan-owned Foxconn, whose production was centered in Henan, opened an iPhone factory in Chennai, India. Both Chinese and U.S. vehicle, tire and car battery factories have set up shop in Mexican cities such as Coahuila, Guadalajara, Monterrey and Tijuana. This work-around, known as “nearshoring,” worries the Trump administration, which believes China could exploit NAFTA and export Chinese cars through the “back door” of Canada and Mexico. The fear helps explain Trump’s unexpected tariff threats against hemispheric neighbors. Meanwhile, China has quietly built an “alternative trade architecture,” according to the Financial Times, in which 40 percent of its exports now go to countries with whom it shares bilateral free trade agreements, excluding the U.S. and European Union, mostly across Asia, but also Australia, Canada and South America.

Nobody can predict what happens next. But if current trends continue, we are living through a collision of economic trajectories, positioned on either side of the Pacific, set in motion 40 years ago: Xi Jinping’s attachment to export-driven industrialization pitted against Trump’s decades-long fixation on protectionist tariffs. This contradiction is the terrain on which much of the world must now maneuver. Something has to give, but tidy resolutions are hard to imagine, for all the same reasons that China differs from Japan. At some point, even Trump’s most vocal skeptics will have to concede that his ideas, in conjunction with Xi Jinping’s, have ushered in a new economic epoch. What began as the rantings of a minor celebrity, first on daytime television and later captured on a camera phone in Las Vegas, now helps to shape the world. The 1980s are dead; long live the 1980s.

- Oprah followed up by asking Trump whether he would ever consider running for the White House. He demurred: “Probably not.” When I show this clip to my undergraduates, their jaws drop. One remarked, “He’s exactly the same guy.” ↩︎

As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.