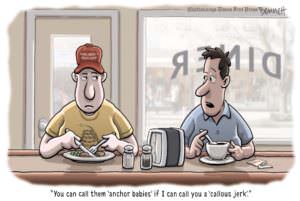

Trump’s War on ‘Anchor Babies’

It’s no laughing matter. A small yet influential collection of academics actually supports his position. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump waves to the crowd after speaking at the National Federation of Republican Assemblies in Nashville, Tenn., on Saturday. (Mark Humphrey / AP)

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump waves to the crowd after speaking at the National Federation of Republican Assemblies in Nashville, Tenn., on Saturday. (Mark Humphrey / AP)

If Donald Trump has learned anything during his long and overblown career as a real estate mogul and reality TV huckster, it’s that flamboyance, belligerence, vulgarity and the allure and promise of supremacy sell.

Truth, fairness and justice—abstract eggheaded concepts all—don’t sell, and have little to do with Trump’s concept of success. All that matters is winning and outperforming the competition. As Trump was recently quoted as saying in an Aug. 15 op-ed by New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd: “I always win. … It’s what I do. I beat people. I win.”

No doubt Trump would have added, had he been asked directly, that the people he beats include babies—or more precisely, “anchor babies,” the pejorative du jour used to describe the U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants, who become citizens at birth under current legal doctrine. Trump wants to wage war on anchor babies and strip them of their American citizenship. He’s made that war the cornerstone of the anti-immigration platform that has vaulted him to the top of the Republican presidential polls.

Say what you will about the Donald, but the man isn’t stupid. When he announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination June 16 and declared that Mexico was “sending” drug smugglers and “rapists” into the U.S., he knew exactly what he was doing. He wasn’t just bemoaning the presence of an estimated 11.3 million undocumented immigrants in our midst, or simply tapping into our long and sorry traditions of nativist scapegoating; he was accusing Mexico of deliberately staging an invasion of the United States. The invasion thesis operates at the center of Trump’s campaign, whose motto is “Make American Great Again.” The thesis is spelled out in greater detail in the “immigration reform” policy the campaign posted on its website in mid-August, and it is central to the thinking behind the policy.

“For many years,” the policy statement proclaims, “Mexico’s leaders have been taking advantage of the United States by using illegal immigration to export the crime and poverty in their own country. … They have even published pamphlets on how to illegally immigrate to the United States.”

To turn back the invasion, Trump’s policy calls not only for tripling the number of immigration agents and conducting mass deportations of the undocumented, but also building the much-ballyhooed 2,000-mile-long impenetrable wall along our southern border, which Trump has vowed Mexico will be forced to fund should he attain our nation’s highest office.

But of all the proposals tendered by the Trump campaign, none is more far-reaching politically or dependent, in a strict legal sense, on the invasion argument than the call for ending “birthright citizenship” for so-called anchor babies. Birthright citizenship, the policy contends, “remains the biggest magnet for illegal immigration.”

But can it be done? Wouldn’t the repeal of birthright citizenship require a constitutional amendment, or more specifically, an amendment to the 14th Amendment of 1868? Amending the Constitution is a cumbersome, time-consuming and highly uncertain process. It’s been done only 27 times before.

Although the Trump campaign’s immigration policy is silent on the amendment issue, the candidate himself, as might be expected, has not been. In an Aug. 19 town meeting in Derry, N.H., Trump told a crowd of ardent supporters that “many of the great scholars say that anchor babies are not covered” by the 14th Amendment. “We’re going to have to find out” by means of a court challenge, he said.

Like many other students of constitutional law, I dismissed Trump’s remarks as little more than the usual hot air and red meat that Republican pols and their echo chamber at Fox News regularly spoon-feed their base. But as the PolitiFact project of the Tampa Bay Times subsequently reported, a small yet influential collection of academics, such as Yale Law School professor Peter Schuck, actually supports Trump’s position. It has also been endorsed by at least one highly respected federal judge—Richard Posner of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Both the legal proponents of birthright citizenship and their opponents begin their interpretations with the text of the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause, which reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.”

The amendment was adopted to overturn the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857, which invalidated the Missouri Compromise and held that African-Americans, whether enslaved or freed, could never be U.S. citizens. Both sides in the current debate agree that the amendment’s central purpose was to confer citizenship upon newly emancipated slaves.

However, when it comes to other groups of people, the two sides disagree sharply over the meaning and purpose of the clause that limits citizenship to people “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S. Those who align with Trump maintain that the clause pertains only to people who declare unswerving allegiance to America and to no other sovereign. It is for this reason, they argue, that children of foreign diplomats born in this country do not receive citizenship at birth.

Nor would the children of foreign occupying forces born here receive automatic citizenship, birthright opponents insist. Although Mexico has not, of course, declared war on America, the Trump campaign regards today’s illegal Mexican immigrants as a de facto invading force. As one anti-immigrant organization—the Colorado Alliance for Immigration Reform—explains the current nativist position: “The correct interpretation of the 14th Amendment is that an illegal alien mother is subject to the jurisdiction of her native country, as is her baby.”

Birthright opponents further buttress their interpretation with invocations of the “original intent” of the framers of the 14th Amendment, cherry-picking various anti-immigrant sentiments expressed during the Senate’s 1866 debates over the measure. They also cite the Supreme Court’s 1884 decision in Elk v. Wilkins, which declared that Native Americans were not citizens under the 14th Amendment, even though they were born within the geographic limits of the U.S., because they owed their allegiance to tribal nations that had their own reservations.

Birthright opponents emphasize that the Elk ruling was effectively overturned with passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. No constitutional amendment was required. Thus, they conclude, if Congress had the power to pass legislation and alter the citizenship status of America’s indigenous population without a constitutional amendment, Congress can also pass new laws to take away the citizenship of anchor babies.

Fortunately, the great weight of legal scholarship is to the contrary. As University of Baltimore Law professor Garrett Epps, the Congressional Research Service and others have shown, the ratification debates taken as a whole indicate that the 14th Amendment was designed to extend citizenship to all people born in the U.S. regardless of the race, ethnicity or alienage of their parents.

Any doubts in this regard were laid to rest by another landmark Supreme Court decision handed down in 1898—United States v. Wong Kim Ark—in which the high tribunal held that the 14th Amendment had to be read according to English common law and the principles of jus soli (Latin for “law of the soil”). Under those principles, people born within the territorial dominion of a nation were recognized as citizens at birth. Construing the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause, the court held that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” referred to anyone who is required to obey U.S. law rather than those formally swearing their allegiance.

Although the Supreme Court has had few occasions to revisit its Wong Kim Ark opinion, it has since expressed its approval of birthright citizenship twice: in 1982 in Plyler v. Doe concerning the right of undocumented children to attend public schools, and again in 1985 in the case of INS v. Rios-Pineda, a deportation proceeding.

In the face of the overwhelming legal authority against them, you might expect Trump and his minions to let anchor babies off the hook and declare a truce in the war against them. Don’t count on it.

If you had asked legal scholars back in 2007 if they thought the National Rifle Association and its allies had a snowball’s chance of persuading the Supreme Court that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to bear arms, most would have smiled and referred you to the vast body of literature and prior case law that advised that the Second Amendment protected gun ownership only in connection with service in a state militia.

Then, along came Justice Antonin Scalia. With Scalia writing for a 5-4 majority, the court purported to divine the original intent of the framers of the Bill of Rights and succeeded in turning the Second Amendment on its head in District of Columbia v. Heller, recognizing an individual constitutional right to bear arms.

I’m not prepared to say that the same kind of turnabout could happen with the 14th Amendment. But neither am I prepared to say it won’t or it can’t.

So stay tuned. Donald Trump’s war on anchor babies is no laughing matter. It’s serious, and it’s just getting started.

Your support is crucial...

As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.