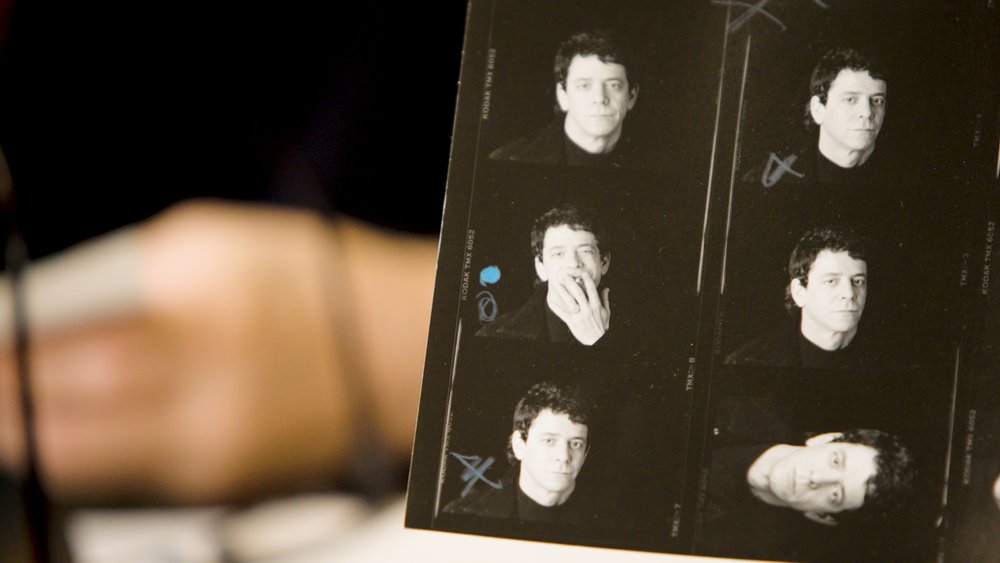

‘Uncropped’: James Hamilton’s Life in Photos

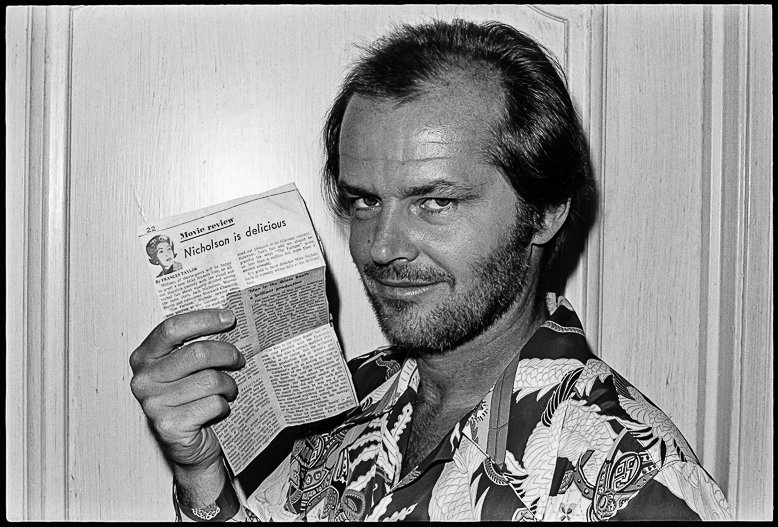

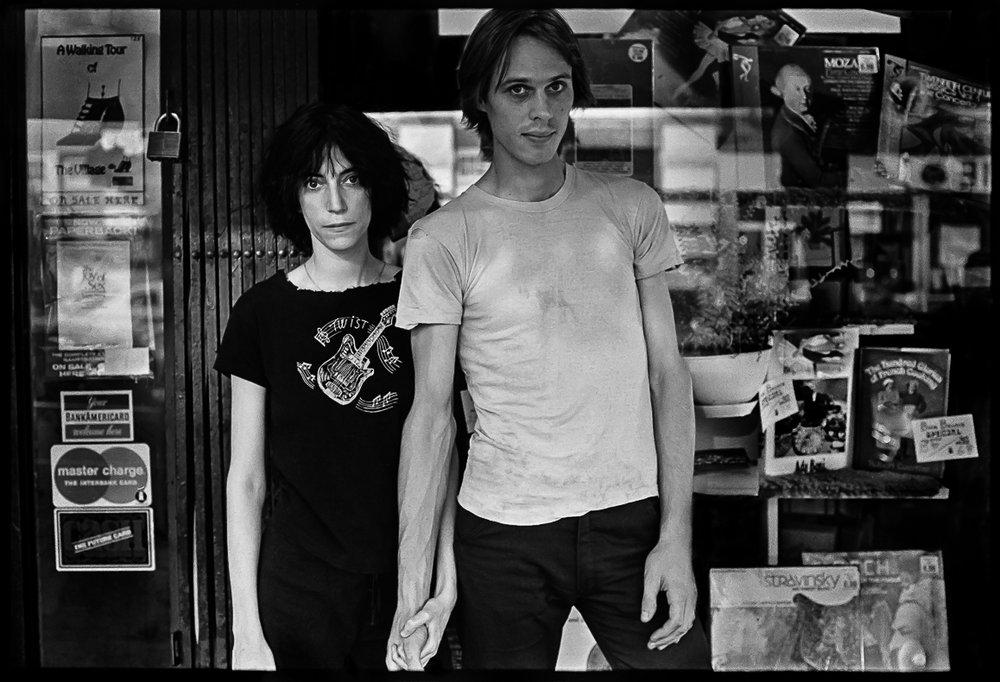

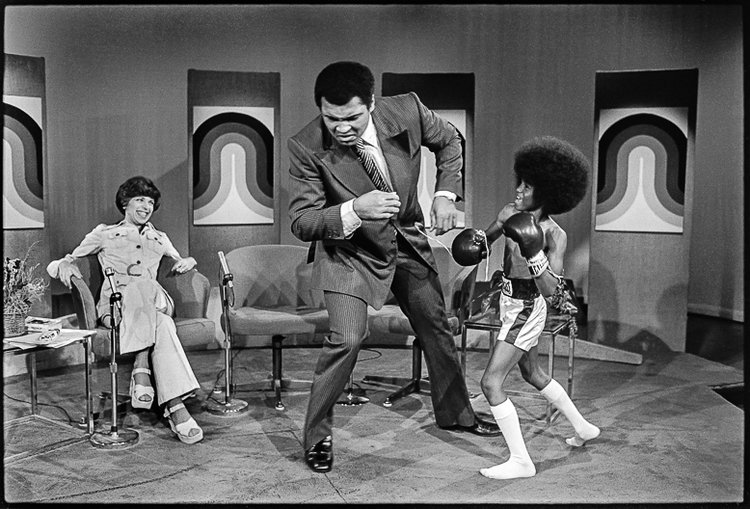

A new documentary chronicles an iconic New York photography career and the death of the media economy that nourished it. 'Uncropped' Courtesy Greenwich Entertainment

'Uncropped' Courtesy Greenwich Entertainment

“Uncropped” opens in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal, and in New York at Manhattan’s IFC Center and the Sag Harbor Cinema, on April 26.

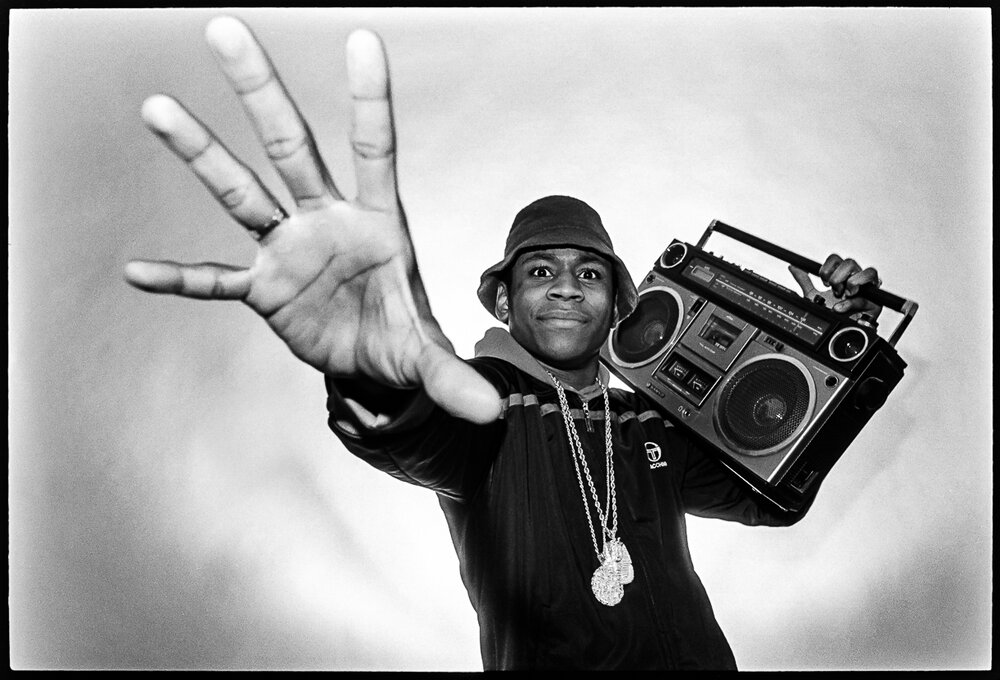

James Hamilton is a photographic auteur with a singular creative vision. In a career spanning more than half a century, he has covered war zones, revolutions and movie sets, from Jerry Garcia to Corazon Aquino to Tiananmen Square. In recent years, he has gained a new generation of admirers by posting decades of his street photography on social media. He is perhaps best known for his work for The Village Voice, the nation’s first alternative newsweekly founded in 1955 in New York City, where Hamilton has lived for six decades in the same Greenwich Village apartment.

D.W. Young’s new documentary of Hamilton, executive produced by Wes Anderson, is a rollicking and stylish portrait of its protagonist and the heyday of the alternative weekly, when classified ads subsidized hard-hitting exposes, bold feature writing and boundary-pushing art and photography. I interviewed Hamilton and Young in New York via Zoom. Our conversation has been edited slightly for length and clarity.

TRUTHDIG: What inspires someone to make a film about James Hamilton?

D.W. YOUNG: Judith Mizrachy, our producer, saw a lot of his earlier work posted on Facebook during the pandemic. She was blown away. The sense of humor. The strength of the personality, the range of emotions. Wes Anderson talks about it being very cinematic. Judith said, “This work is amazing and hasn’t been seen as much as it should be. What about a documentary about James and his photography?”

TD: James, what and who drew you to photography?

JAMES HAMILTON: In 1966, I was studying painting and drawing at Pratt. Normally, in the summer, I would’ve gone back to Westport, Connecticut, where I grew up. But a couple of my friends got an apartment in the Village and said, “Why don’t you stick around for the summer?” It was $109 [laughs] in a great neighborhood just north of Washington Square. The summer of ’66 was a great time to be in New York. I had to get a job to pay for this $109 apartment, [split] three ways, so through a friend of a friend, I got a job working for a fashion photographer who needed an assistant.

I went to see this guy who was just starting out in New York, a Roman named Alberto Rizzo who specialized in fashion and beauty and was setting up a studio. I knew nothing about photography and bluffed my way in. I didn’t know what a strobe was or anything about studio work. But we found out we both loved noir films from the ’40s and ’50s. He hired me on the spot and I learned on the job. I spent the summer wandering around the city using his camera, learning how to develop film, make prints and work in the studio. At the end of the summer, I decided this is what I’m going to do. I never went back to Pratt and I became a photographer. My roommates moved out and I still have that apartment.

TD: Almost 60 years later, how much do you pay for rent?

HAMILTON: One hundred and forty-seven dollars. Rent control.

TD: You were there for The Village Voice’s heyday, when Nat Hentoff, James Ridgeway, Jack Newfield, Wayne Barrett, were among its writers, when “New Journalism” was in vogue. What role did the alternative press play in your career?

HAMILTON: That was my fourth staff job. I’d worked at a rock and roll paper called Crawdaddy, then at a newspaper called The Herald, which was a Sunday broadsheet that had a brief life in New York. It was designed by Massimo Vignelli, it was gorgeous. Then I got hired away by Harper’s Bazaar and was staff photographer there for a few years, doing mostly portraits and endless parties. I was their kind of paparazzo. Then they did a redesign and had no more need for a staff photographer.

I started off freelance for The Village Voice, then they hired me and I stayed there for 20 years — 1973 to 1993. It was a great, great time in journalism and a great time for the Voice, and fantastic for me. When I first started, I worked half a block away, because they moved into my neighborhood.

That’s the kind of story we would do, pretty much anything we wanted. In other words, we’d come up with an idea and the next day we were on the job doing it.

I was with them all those years. That cast of characters you mentioned were all great writers. I wound up pairing off with writers, I’d go do stories with them. A lot of time I’d go off on my own. But it was great to have writers to work with, alongside. Michael Daly — who became very well known in New York as a newspaper reporter after the Voice — and I once were driving around the Bowery and noticed that there were not only elderly derelicts but young guys. So, we said, “Why don’t we do a story?” We started hanging out there; Michael actually wound up staying at flophouses. We were basically undercover. It was one of those jobs that I did very few pictures on because my camera was hidden in my coat.

That’s the kind of story we would do, pretty much anything we wanted. In other words, we’d come up with an idea and the next day we were on the job doing it. I had lots of assignments, but many of the stories we did were self-starters. If I wanted to meet somebody, like the director George Romero, I’d say, “Why don’t we do a story about George Romero?” The next day I’m flying to Pittsburgh taking pictures of Romero in the mall where he shot “Dawn of the Dead.” We became great pals, and he said, “Why don’t you become my still photographer?” So, I became the still photographer on films.

At the Fillmore East and I photographed [a lot of musicians] onstage and off: The Allman Brothers, The Doors, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jethro Tull, Big Brother & The Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Albert King, Santana, Country Joe McDonald & The Fish, The Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, B.B. King, The Byrds, Led Zeppelin, Mothers of Invention, Miles Davis, Taj Mahal, Johnny Winter, Van Morrison…

I processed all my film and printed in my apartment and kept everything I’ve ever shot. And I own everything I ever shot.

TD: The Voice’s Richard Goldstein, who’s also interviewed in “Uncropped,” describes the Voice’s aesthetic as: “The merger of art and journalism.” What does he mean?

YOUNG: I don’t want to overly interpret Richard’s take, but an additional part of that quote is key, because he talks about them being in a state of constant conflict — almost a dialectical state. They’re both present — art and journalism — but they’re never at ease with each other. That’s very important as far as the Voice is concerned, the sense that they’re both pushing. But the idea that you’re allowed to pursue aesthetic interests at the same time and that was not less valid than the political. This coexistence of the two, the uneasiness of the relationship, is what Richard is talking about.

Examples are helpful to back up Richard’s point. On the writing side, Jill Johnston writing without punctuation drove people crazy, yet she was allowed to do it. That’s not normal for a newspaper, right? Greg Tate writing about post-structuralist theory. Stuff so outside the norms of what is expected from a newspaper — it was not only allowed to exist, but to proliferate, really.

HAMILTON: I had an art background, so I thought of everything I did as my art. But I also thought of it as my personal journal, my personal history. I always had the history of my life and the life of New York on my mind when I was taking pictures. I started out taking pictures in the street and just wandering around with a camera doing all of that. Everything I did from the beginning came from the experience of wandering around and only taking pictures for myself. I was never allowed to be a hack. I was always shooting for myself, keeping all of the work close at hand, close to hand, developing and printing everything myself. I could not think of it as anything else but my art, my craft, my business, my life. Journalism was a title, but I always thought of it as my work and personal view of things.

Everything I did from the beginning came from the experience of wandering around and only taking pictures for myself.

I was allowed at the Voice to have that point of view throughout. They never cropped my pictures, ever. I had a wonderful art director who I met at Pratt. We understood each other; he loved photography. There was a co-staff [photographer] there named Sylvia Plachy, whose work was different enough from mine that we got along very well. She had the same privileges. She could do anything she wanted. She even had a page called “The Unguided Tour,” which was a picture she took of anything she wanted and it [ran] every week. So, it was that kind of freedom we were allowed. Having a great and considerate art department, and writers telling great stories all contributed to, as Goldstein said, great art and great journalism.

When Cory Aquino was trying to run the Philippines, and celebrating people’s power, the Voice actually sent Joe Conason and I to the Philippines to cover her [presidential] campaign. We came back, did the story, published the pictures and then Marcos was overthrown [laughs] and they sent us back to the Philippines. Not a lot of alternate weekly publications would have done that, I don’t think.

I covered lots of wars. Joe and I were at Tiananmen Square when it [the 1989 protests] happened. We’d been nagging them to send us there. Then, when it looked like it was all going to be over, they said, “Okay, you can go.” We went with a young woman translator and joined Chinese students, and it all happened, the massacre. We sent our film out of murdered students which ran on the cover of the Village Voice — nobody had those pictures. It was remarkable that they would do that in those days.

TD: Joe Conason says in an interview in “Uncropped,” “James was an adrenaline junkie.” What does he mean?

HAMILTON: [Laughs.] Pretty much that I was a fool. I took risks that I should not have taken. War photography did not come naturally to me, but getting the picture came naturally to me. I probably did things I should not have done. I put maybe both of us in danger.

TD: What part did Rupert Murdoch play in the demise of the Village Voice?

YOUNG: From my understanding, he didn’t play any part in it. What’s interesting, when he bought the paper [in 1977], he was actually subsidizing the [New York] Post with the Voice. Which is a crazy thing, if you think about it. Because the Voice was making a very nice amount of money for him at that point. But then he sold the paper [in 1985] and he didn’t hold onto it too long. From him, it started the chain of a succession of increasingly problematic owners that got more and more problematic. Tricia [Romano’s] book outlines that fairly well.

TD: James, you mentioned working for the New York Observer. Was that boy wonder Jared Kushner as qualified to be a publisher as he was to be a White House adviser and the head of a private equity firm financed by the Saudis? Joe Conason says in the film that Kushner “turned a broadsheet into a tabloid.”

HAMILTON: I was there 15 years. Basically, I was lured away from the Voice. They said I could do two pictures a week, anything I wanted. Same as what Sylvia had, only there were two and were quite large. It became like my column, in a sense. I called it “Two and Four,” because there was one on page two, then you turned the page, and there was one on page four. I’d make a game of it, because I had to set some limitations for myself, because I could do anything I wanted. I’d have some subtle link to each other, something about them would be ironically similar. All those years, every week — a set of two pictures. And I did all the other pictures in the paper, too. It was a lot of work and a lot of fun.

Then, the last few years, yes, Jared Kushner bought the paper and was much more concerned with business and real estate. I was photographing suits and offices, and it became no more fun. They eliminated the two pictures and made it just one picture, and it had to be a portrait of someone in town that week. I felt like I was working for the paycheck, which was something I’d never, ever done. It was a bad time in my career.

TD: Why did you title the film “Uncropped”?

YOUNG: It was my title. We struggled with titles for this, because how do you pin James down? How do you pin down all of the many facets of his work, his career, the places where he’s worked? It’s representative of the way he was able to work with so much independence and control over his work. There’s another level of meaning about the publications themselves, like the Voice, existing in a similar way.

TD: In cinema, a handful of directors have “final cut.” I guess one could say James had “final crop.”

HAMILTON: [Laughs.] David [D.W.] had final cut, too. I admire people who have final cut.

TD: James, tell us about your photographic sensibility?

HAMILTON: I always thought of the work as a history, personal and otherwise. A lot of the pictures are stories. I was always very aware of composition — that came from drawing and painting and my art background. I got past the camera to the extent that I could be very spontaneous and clear and aware of composition, spontaneously. My pictures are pretty well composed.

I learned so much in the street. I don’t call that my “street” — I call them my “random” pictures, basically pictures on the way to jobs. My background was very much wandering around New York. That’s what I loved doing most. To the point where I look back at pictures and I can’t even remember taking them, because I was always working, always taking pictures. I’m amazed sometimes when I see pictures that I just have no recollection of ever even being in that location and taking that picture.

TD: What cameras do you prefer?

HAMILTON: I started out with a Nikon F 35mm camera. I’ve only used two cameras in my career. I borrowed the Nikon Rangefinder from the photographer that I worked for and used that for a little while. Then I bought the Nikon F, and used that up until the mid-80s. Then I was doing covers and full pages for New York magazine, and the format meant that if I was going to have a full page, they would have to crop my 35mm frame. So, I switched cameras to a Pentax 645, the negative or transparency was the same format as that page, so they would not crop my pictures [laughs] if I used that camera. Then I fell in love with that camera as a medium format camera, the quality was really great. I used that from the mid-’80s until now.

I started shooting digital because I had to. I was working on a film, doing stills for a movie, and they wanted digital images. Up until then I was using this big clunky, noisy Pentax 645 without a blimp, a silencer, so I’d run in and take pictures at the end of a scene. Obviously, I wouldn’t shoot during the scene. When I was working with Wes Anderson he was fine with that. And Noah Baumbach, as well. That’s how I shot those films. Then, once I worked on a film and they required I got a digital camera, starting in 2007.

TD: Earlier in this interview, and on screen, you state that you “own everything” and “only handed in what you wanted” and publications “never touched the negatives.” Why?

HAMILTON: When I was working at Harper’s Bazaar, I’d see them throwing out prints and negatives. I just never wanted that to happen. And I’d never have anyone develop my film anyway. I did a job for the London Sunday Times, they sent me to Ethiopia to cover the war, and I said I’d do it, as long as when I finish — which turned out to be months later — I can use your darkroom to do all my own developing, and they said fine. It was that important to me that I have control over the processing of my work, prints and negatives. It’s important to me because it’s a matter of control.

TD: Where can we see your pictures now?

HAMILTON: During the pandemic, I had time to organize and edit my photos and put them online. And I did a book. After a car accident that destroyed my leg, Thurston Moore, from Sonic Youth, who publishes books, said, “Why don’t we do a book of your musicians?” While I was laid up, we did “You Should Have Heard Just What I Seen,” a line from a Bo Diddley song.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.