VIDEO: Chris Hedges: In Extreme Times, ‘Liberals Are a Dead Force’ (Part 1 of 3)

On The Real News Network's "Reality Asserts Itself," Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges discusses the significance of Thomas Paine, why we did not carry out an American "Revolution," and three reasons why liberals cannot "propel resistance forward."

On The Real News Network’s “Reality Asserts Itself,” Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges discusses his book “The Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt” with Paul Jay. In part one of a three-part series, they focus on the revolutionary significance of Thomas Paine, why we did not carry out an American “Revolution,” and three reasons why — in moments of extremity — liberals cannot “propel resistance forward.”

“…I think that rebels are absolutely vital,” Hedges says. “You know, I use that concept from Reinhold Niebuhr about sublime madness. And Niebuhr writes correctly that in moments of extremity, liberals are a dead force. They are too ineffectual, too little emotional, too intellectual in order to propel resistance forward, that you need people who are possessed of that sublime madness.

“And the figures that I seek out in the book–Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, Lynne Stewart, the great civil rights attorney, herself sent to prison and then released because she has stage IV cancer, Mumia Abu-Jamal, they are figures who I think are possessed of this sublime madness.” (Transcript follows the video below).

Truthdig is pleased to announce the upcoming DVD release of Hedges’ complete talk about his latest work, “The Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt.” The DVD will include a moderated discussion by Truthdig columnist and “Uprising” host Sonali Kolhatkar.

–Posted by Jenna Berbeo

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself.

In his new book, Wages of Rebellion, Chris Hedges writes the following: Rebels share much in common with religious mystics. They hold fast to a vision often they alone can see. They view rebellion as a moral imperative even as they concede that the hope of success is slim, at times impossible.

Further down, he writes: Revolutions take time. They are often begun by one generation and completed by the next.

Towards the end of the book–I should say, at the conclusion of the book, Chris writes: We must grasp the harshness of reality at the same time as we refuse to allow this reality to paralyze us. People of all creeds and people of no creeds must make an absurd leap of faith to believe, despite all the empirical evidence around us, that the good draws to it the good.

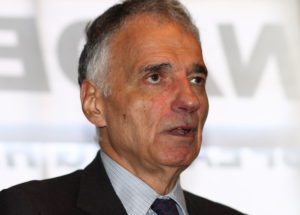

Now joining us to discuss his book in the studio is Chris Hedges.

Thanks for joining us, Chris.

CHRIS HEDGES, JOURNALIST, ACTIVIST, AND AUTHOR: Thanks, Paul.

JAY: So everyone knows Chris. Chris is a regular contributor on The Real News Network, also at Truthdig. But just quickly, he’s a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. His books, 11 books, include Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, and The Triumph of Spectacle, and War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. His latest book, which we’re going to be talking about today, is Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt.

And he’ll soon be hosting a new show, a TV and internet show, Wages of Rebellion, for teleSUR that will also appear on The Real News Network.

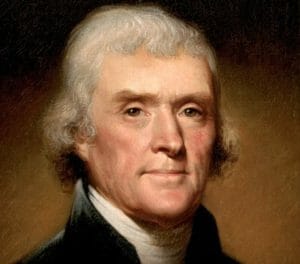

So this book is so rich and layered, and we can just start getting a crack at it. There’s a figure in the book about two-thirds of the way through, and you make the basic argument, essentially–I mean, I would phrase it that the current elite is simply not fit to rule and that the capitalist system–and in various ways you show how it’s ruining peoples lives. And then you jump to a historical figure. You talk about Tom Paine. And why is Paine of such significance in this story? And what do we learn from his life today?

HEDGES: Because he is the only authentic revolutionary that we’ve created, although he didn’t come to the United States until he was 37. We’ve produced a slew of great anarchists–Berkman, Goldman, both born in Russia; great resistance figures, Sitting Bull, Frederick Douglass; but very, very few revolutionaries. It is not within our DNA. And so Paine is an extremely important figure, especially at the advent of what we call the American Revolution, although I think that’s a misnomer. The American Revolution was a colonial war overthrowing the major imperial power of its day, Britain, and had the characteristics of a classic fight by an oppressed colonial population against a colonizer.

But Paine understood power in a way that Benjamin Franklin, Jefferson, all of the leaders leaders, Adams, didn’t, because if you go back and look, when they began their revolt, they were hoping to make an accommodation with the British Crown. And Paine said, you don’t understand how imperialism works, you don’t understand the hubris that comes with that kind of power, you don’t understand that these people are not interested in making an accommodation with you. And so he served many vital functions, not least of which was articulating the call for revolution, not only in Common Sense, but in the Crisis papers. He was by far the most read author of the 18th century, both in Britain and the United States.

JAY: Very important in terms of mobilizing the American working class to fight for the revolution.

HEDGES: Yes, and he consciously wrote in the language of the working class, unlike Edmund Burke, his nemesis, who wrote in that classic kind of florid style that academics still use today. And that’s why we can’t even count the numbers of sales of Common Sense, because you would have large numbers of people who were illiterate who were being read Paine. And Washington at Valley Forge had that, you know, “These are the times that try men’s souls”, had all this stuff read out to his troops who were fleeing in droves that winter.

So Paine is an extremely important figure. And I like Paine as a kind of model, because he was a revolutionary or a rebel to the core. So as soon as the slaveholding–he was an abolitionist, by the way, and condemned the American revolutionaries for not abolishing slavery, if we’re talking about freedom while large numbers of African Americans were enslaved.

And so once–and the only reason the elites worked with him is because in Pennsylvania, the entire colonial government remained steadfastly pro-British. And so it was always an uncomfortable alliance. But Paine was all they had.

JAY: Now, Paine in your book emerges as sort of a person that represents this kind of revolutionary that you’re describing, but he did support a successful revolution. It wasn’t without–.

HEDGES: But it wasn’t a revolution. I mean, we call it a revolution, but it wasn’t. It was the overthrowing of a colonial occupier and the replacement of that occupier with the native aristocracy. And that’s not what a revolution is. That’s more akin to what we saw in Algeria overthrowing the French occupier and replacing it with an indigenous Algerian government. So I think that’s an important distinction. We did not carry out a revolution.

JAY: Well, in the leftist literature, they would call it a bourgeois revolution.

HEDGES: But it’s not even a revolution. It’s a colonial war. I mean, we had Prussian mercenaries. We had the largest armada that Britain had ever amassed besieging New York. It was really an example of an uprising against a foreign imperial power.

I mean, [incompr.] Paine. You know, what makes Paine a rebel is that after the Revolution, he names the crimes of the elite, including Washington, who became, arguably, the wealthiest man in America by speculating on Indian lands, seizing native lands across the dividing line and then selling them. And so he became a pariah after the Revolution because he remained a revolutionary.

JAY: And they didn’t need him anymore.

HEDGES: No, and he was–he did not buy into the disenfranchisement of not only African Americans, but Native Americans, women, and certainly white men without property. This was all an anathema. He was as close to, at that time period, we could come to having a socialist. And he talks about social programs and pensions and all that kind of stuff.

So when he dies, I think about 1806, in New York after going to France and being imprisoned for denouncing the regicide and the reign of terror, six people, three of whom were black, came to his funeral. He was a completely forgotten and neglected figure because he held fast.

JAY: Because he held fast, he was so marginalized. So what do we learn from that?

HEDGES: Well, we learn a lot of things. We learn that when you hold fast to that moral imperative long enough, you’re going to pay a price, that elites, even elites that you may initially support, once they are in positions of power, they don’t want that kind of critique around.

JAY: Why did he lose his popularity in the American working class? Or did he? I mean, why does he end up with only six people at his funeral after being one of the most read authors during the revolutionary period?

HEDGES: Because he was vilified in the press through really vicious forms of character assassination because he was an atheist. And they found a point within his writings that would allow him to be demonized to the wider public. That’s why. That’s The Age of Reason, which he wrote when he was in Britain fighting Pitt.

JAY: And why does he become this very important figure in your book in terms of what we learn from that today?

HEDGES: Because he holds fast to the moral imperative of revolt and he’s willing to pay the price. I mean, I think that we have to look back at history and realize that most rebels don’t succeed. We remember the ones that do, but they’re the exception. Most people who rise up and rebel against monolithic systems of power get crushed. And that doesn’t mitigate the magnificence of their lives and their resistance. That’s just a reality. You know, if you take that path, the odds are against you. And yet I think it’s the path that we have to take, because rebellion, especially when we face this monolith of corporate power we call radical evil, there is a moral imperative to stand up to that power with the realization that in all likelihood, especially in a prolonged act of resistance, that power will crush us.

JAY: Isn’t there a danger in that, which is, if you don’t set your sights on winning, whatever that path to winning is–and I’ll take you back to the quote your book, that sometimes it needs to be one generation handing off to the next; you know, however long it takes, if you don’t do what’s historically possible as the next steps towards winning and create a vision for winning, it’s very hard for people, especially if you’re trying to develop a mass movement, that people are going to go into something saying, we’re going to lose, but let’s go anyway. People need a vision to fight for. And you’ve said it yourself, and we talked about this in one of our earlier interviews, that one of the great weaknesses of the American left is they’ve never articulated a viable vision of socialism, so there’s nothing to fight for.

HEDGES: Right. Well, you certainly need a vision, and you need to believe on some level that that vision is attainable. On the other hand, it doesn’t help you as a rebel not to be able to read the reality in front of you, because then you’re reacting to an illusion, you’re reacting to kind of happy thoughts.

Hannah Arendt, I think, grasps this when she looks back on her own resistance to the Nazis. I mean, she leaves the University of Heidelberg and she says that she had to unlearn everything she had been taught by Heidegger in the University to become a moral human being. And then she joins–she was not a Zionist, but she joins a Zionist underground movement to smuggle German Jews to Palestine. She’s eventually picked up by the Gestapo, stripped of her German citizenship, becomes stateless–she was almost killed by the Gestapo–and ends up in France as a stateless person.

But she says, number one, I look back on that time period of my life and I say, thank God that I wasn’t innocent, that to be innocent in a time of radical evil is to be complicit, number one. And number two, she says those who are most effective at resisting or not those who say, we shouldn’t do this, this oughtn’t to be done, but those who say, I can’t. And I think there’s something within the DNA–that’s why rebels are very poor–. Once power is attained, rebels very rarely are able to rule, because they have that inability to compromise. You saw it with Che Guevara. I interviewed Ronnie Kasrils in the book, who founded the armed wing of the ANC with Nelson Mandela and becomes the deputy defense minister under Mandela, and he starts criticizing the corruption, the creation of what would be called the new class among the ANC. And then they fire on the miners who are striking–the largest massacre since the Sharpeville massacre–and he denounces his own party, a party that he spent 30 years underground at the risk of his life fighting for. That’s a rebel.

And Kasrils makes an interesting point in the book. He said, I was a rebel, because he’s white, he’s Jewish, he walks out on his own, he actually literally walks into a township–you’re not, as a white person, allowed to be in a township after ten at night–and he doesn’t go back, and he never goes back. And he said, I was a rebel; Mandela was a revolutionary, in the sense that he didn’t rebel against his own. And I think that’s right.

But I think that rebels are absolutely vital. You know, I use that concept from Reinhold Niebuhr about sublime madness. And Niebuhr writes correctly that in moments of extremity, liberals are a dead force. They’re are too ineffectual, too little emotional, too intellectual in order to propel resistance forward, that you need people who are possessed of that sublime madness.

And the figures that I seek out in the book–Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, Lynne Stewart, the great civil rights attorney, herself sent to prison and then released because she has stage IV cancer, Mumia Abu-Jamal, they are figures who I think are possessed of this sublime madness–and Jeremy Hammond’s in the book. A lot of these interviews are in prisons because they also remind us of the price, that when you effectively defy the state, the price that you often have to pay, which is why the book was called Wages of Rebellion.

JAY: I find perhaps a little contradictory in the book, the revolutionaries have a faith. Well, I guess it seems to me they have a faith they will win. They don’t always win. I think there’s a certain faith that eventually the people, the people’s interest, will triumph, and if we don’t succeed now, we’ll move the football a little further down the field and we’ll succeed next time, which it seems to me you do have a sense of that. On the other hand, it’s we fight fascists because they’re fascists, even though we’re probably going to lose.

HEDGES: Oh, I didn’t write that.

JAY: Close.

HEDGES: I wrote, you know, I fight fascists not because I’m going to win, but because they’re fascists, that it’s the wrong question. Obviously we want to win, but ultimately we have a moral imperative to fight, let’s call it again radical evil, because even if we fail–at this point talking about climate change, talking about the creation of a kind of global neo-feudalism, the most frightening form of totalitarianism in terms of the security and surveillance state, the militarization of police, etc., the stripping away of our most basic civil liberties, it’s all been taken from us. And it comes down to something as visceral as being a father. I have four children. So I may fail. But I at least want my children to look back and say they tried. We are squandering the future of the succeeding generations, and we have a moral imperative of revolt. I’m going to try every way possible to win. But if I fail or if we fail, if we descend into a very frightening dystopia that people like Julian Assange and cypherpunks have predicted, that doesn’t invalidate resistance, because finally you resist not for what you achieve, but for who it allows you to become.

And in kind of theological terms, the forces that we are battling are forces of death. They are exploiting and exhausting human beings, the natural world, until there’s nothing left. And that makes those of us who are resisting these forces battling, in essence, on behalf of life. And that’s a moral imperative. And yes, we want to be–I mean, I fought the black bloc over these issues, over what’s effective, what isn’t [incompr.] those are important issues.

But we can’t allow the certainty of success to be that which drives us forward, because the moment we make a setback, it becomes easy to become demoralized or cynical or fallen to despair. And that’s what I think all great rebels or revolutionaries have is a faith. I mean, ultimately you have a belief, as I write at the end of the book, that the good draws to it the good. It may be that we don’t see success in our lifetime. There’s nothing empirically to justify this belief. I mean, the Buddhists call it karma. But it is an absurd leap of faith. But it’s real, and I do believe it, and even though I can’t justify that rationally.

JAY: I guess that’s where we differ, ’cause I think it is leap of faith, but you can justify it rationally. Like, we were having an argument off-camera what the title of Chris’s new show is going to be, ’cause we’re involved in producing it. And Chris was going to call it–wanted to call it–well, I think–I don’t know if you were half joking–Into the Abyss. And I would say, how about Out of the Abyss? And that, like, if you look at personally why do I keep going, you know, I’m hoping The Real News plays an important role in this transformation we’re trying to achieve. We picked trying to break through in Baltimore as the point where we can perhaps do something original and get to a mass audience and maybe help change the political culture here. Does it succeed in the first five years, the first 15 years, the first 50 years? I have no idea. Does it succeed at all? I have no idea. I think we have a good shot at it.

But I guess the context for me is we’re on this very, very long journey from ape to human, animal to human, and we’re very small way down that road. And the sentence I was really struck by here, which is this we do need to pass this struggle on to the next generation, but in a very conscious way. Like, we need to build some stuff now that our kids–our kids are going to make their own choices, but the next generation can then have something to build from, ’cause people in our generation, you and me, we weren’t left very much. Like, the 1960s almost had to start all over again.

HEDGES: Right. Well, that’s right. I mean, it’s a kind of patrimony. It’s a patrimony I was given by my father, who was an activist in the ’60s in the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, and finally the gay rights movement, for which the church kind of pushed him out. And that is a patrimony. And it’s something that I want to give to my own children.

I want to succeed. I do everything possible to succeed. But that’s not finally what’s important. It’s important that you resist, because if you don’t resist, you are complicit with the obliteration of everything that is about justice, everything that has to do with the sacred, everything that has to do with our stewardship over the ecosystem, to make it possible for future generations to survive, and not just human beings, but all species. I mean, in many ways, this is the kind of fight for our life.

Yet if you go back and look at studies of how civilizations have collapsed, Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies, Redmond’s ancient environments and their impacts, and Ronald Wright, A Short History of Progress, and all this stuff, you see that we are devolving the way civilizations always devolve: corrupt elites, extraction of scarcer resources at a higher cost, increased repression to keep the masses in place, retreat into magical thinking. You know, you can just tick it off. The difference is that when we go down this time, the whole planet goes with us. Why–I don’t think human nature has evolved that much that just on a purely kind of coldly intellectual level we should be any different. I pray and hope that we are, and I’m fighting in every way possible so that we don’t go that route.

On the other hand, it’s not helpful to fall into a kind of Pollyannish, you know, victory is assured, which is a form of self-delusion. You know, you saw that with early Marxism, where everybody was convinced–you know, Bakunin, Trotsky–everywhere else, that revolution was going to sweep over Europe, and the industrial might of Germany would be wedded with the agrarian might of–I mean, it was insane. They stopped being able to read reality, because they were mesmerized by their own ideology, their own self-delusion. And those of us who are resisting cannot allow that self-delusion to take over, because once we’re unhinged from reality, we become ineffectual in terms of our ability to resist.

And that is the existential struggle of our time. To just ingest the reality of what climate change will do to the human species even if we stopped all carbon emissions today is extremely frightening, to understand that, the magnitude of losing the Arctic, the polar ice caps, which is happening as we watch.

And what is the response of the elite, courtesy of Barack Obama? It’s to send Shell oil up there to drop half billion dollar bits to profit off the death throes of planet Earth. That is the reality that we live in. And all of the force and all of the momentum is on the side of those who are killing us.

JAY: Okay. We’re going to continue this discussion. Please join us for the continuation of our chat with Chris Hedges on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.