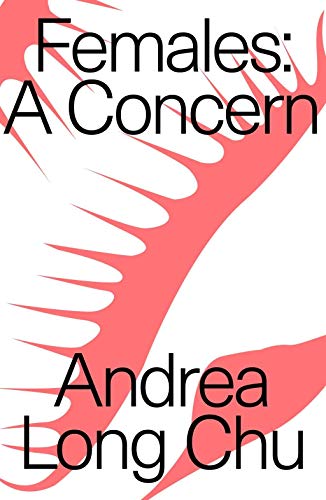

We Are All Female and We All Hate It

A new book redefines “female” as the universal experience of “let[ting] someone else do your desiring for you, at your own expense.” Rogelio V. Solis / AP

Rogelio V. Solis / AP

EVERYONE IS FEMALE.

The worst books are all by females. All the great art heists of the past three hundred years were pulled off by a female, working solo or with other females. There are no good female poets, simply because there are no good poets. A list of things invented by females would include: airplanes, telephones, the smallpox vaccine, ghosting, terrorism, ink, envy, rum, prom, Spain, cars, gods, coffee, language, stand-up comedy, every kind of knot, double parking, nail polish, the letter tau, the number zero, the H-bomb, feminism, and the patriarchy.

So begins “Females,” the first book by critic Andrea Long Chu, whom you may know as Twitter’s @theorygurl or as the author of expertly savage recent reviews in Bookforum, Affidavit, and others. As this opening indicates, “female” is an existential category for Chu, defined not by genitals or modes of performativity, but rather by the universal, constitutive experience of “let[ting] someone else do your desiring for you, at your own expense.”

Whether or not you agree with Chu’s argument is, I think, somewhat beside the point. Certainly there have been many pixels spilled by those who, in rather predictable fashion, are either with Chu or against her on the questions of trans identity and affect, biological and performative accounts of sex and/or gender, and psychoanalytic accounts of desire. In this, Chu finds herself in much the same position as one of the critical voices to whom “Females” is so attached, Valerie Solanas, a multi-hyphenate thinker best known for writing the “SCUM Manifesto” (1967) and for shooting Andy Warhol in 1968. In “SCUM Manifesto,” Solanas upended our understanding of gender, claiming that all traits culturally understood as female (e.g., passivity, vanity, frivolity, weakness) are actually male traits, and that those traits understood to be male (e.g., forcefulness, dynamism, decisiveness, courage, vitality) are actually female traits. For Solanas, the behavior of men — screwing, engaging in wars, et cetera — is an endlessly hopeless endeavor to “prove” that they are, in fact, men in the ways patriarchal culture has defined the term. Men are female, to summarize Solanas’s argument, and they hate it. Chu takes this claim and inflates it another degree: we are all female, and we all hate it. Thus, like a latter-day Solanas, Chu attracts heat from all sides: the feminists who will rankle at “female” being rendered so negatively, so abjectly (“You do not get to consent to yourself — a definition of femaleness.”), without any sort of recuperative transformation; the TERFs who will claim that a pure and holy and politically powerful femaleness is here being sullied by a trans writer who can’t possibly understand womanhood (“To be female is to be an object”); the incels and manosphere members who I can imagine furiously typing their repetitive Reddit replies to one another about a radical trans agenda of “manocide.” In effect, everyone who would be pre-programmed to dislike “Females” will find reasons to do so.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Females” at Google Books.

To be sure, Chu leaves a great deal of room for doubt throughout the text, wondering herself whether “what you’re reading is a feminist text,” whether she wants it to be a feminist text, and acknowledging a “preference for indefensible claims” that she shares with Solanas. But if we sidestep the norms of reception — questions of whether an argument is to accepted or rejected, whether it is good or bad — we are forced to sit, rather uncomfortably, with an ambivalence that beats at the heart of “Females’” reading of the interrelation between desire, power, and identity. You see, if we are all female, and we all hate it, what we actually hate is our entrapment in a structure of desire in which the central agent isn’t us, in which our desire isn’t our own, but rather someone else’s. “Gender is not just the misogynistic expectations a female internalizes,” Chu explains, “but also the process of internalizing itself, the self’s gentle suicide in the name of someone else’s desires, someone else’s narcissism.” Facing that structure of desire means facing the ways in which our agency, our power, is compromised in a culture that places positive emphasis on independence and domination (typically rendered as “male” traits in patriarchal culture) while deriding dependence and submission (typically rendered as “female” traits that we’d best avoid). To get a grip on this in a slightly different register, consider the culture’s celebration of the tomboy (the boyish girl) against its revilement of the sissy (the effeminate boy). Both step out of the rigid boxes of gender, but only one of them in a direction mainstream culture treats as potentially redeemable.

What Chu is saying is something that most of us have experienced in one way or another with more or less awareness. This is, for example, at least one part of the narrative arc of coming out: before coming out, you’re closeted and you perform as if you were merely any average cisgender heterosexual; then, in the process of coming out, you agglomerate to yourself aspects of an “out” identity that circulate in public space and media (gay slang, modes of dress, ways of holding oneself in public, cultural references and preferences) in order to advertise yourself as out, as available to the community for sex, for friendship, for yourself. Much like the hermit crab, we spend our lives collecting pieces of a self from elsewhere, and those pieces provide the protection of recognition, of being a verifiable, readable self for someone else. Think, for example, of the many decisions you make about your appearance every time you’re getting ready for a night out. This, for Chu, is the existential condition of being female: we adorn and perform ourselves in service of another, we desire to be desired by that other, and it is this condition of objectification, abjection, and submission that we abhor most because one of the foundational messages of mainstream culture is that we should desire to be otherwise: that, in the existential terms that are Chu’s frame here, we should want to be male and not want to be female. “This is the root of all political consciousness,” Chu explains, “the dawning realization that one’s desires are not one’s own, that one has become a vehicle for someone else’s ego; in short, that one is female but wishes it were not so.”

It is here where Chu’s book adds the wobble of ambivalence — namely, that we also want to be subject to another; that we may, in other words, not want power or capacity, but its opposite. This point comes out clearest in Chu’s engaging writing on sissy porn. As a genre, sissy porn can be described as porn that involves cross-dressing, male-to-female role play in which a male imagines himself as the most loathed form of masculinity: the boy who acts like a girl. For this reason, sissy porn often traffics in costumes associated with the more absurdist cultural visions of femininity: lace stockings, hot pink lipstick, schoolgirl outfits, patent leather mary janes, panties (usually lacy, and in varieties of pink or white). Sissy porn also relies heavily on narratives of forced feminization, the notion that the boy is compelled to become a girl by some other agent, often through the trope of hypnotic suggestion. What you’re watching when you watch sissy porn, Chu argues, is a narrative about what porn does to you as you consume it: it makes you into a female, it makes you into a subject for another’s desire. “Did sissy porn make me trans,” Chu writes.

At the very least it served as a neat allegory for my desire to be female — and increasingly, I thought, for all desire as such. Too often, feminists have imagined powerlessness as the suppression of desire by some external force, and they’ve forgotten that more often than not, desire is this external force. Most desire is nonconsensual; most desires aren’t desired.

Porn is important territory in this analysis because it is where we confront our desires most privately, in the sense that we select porn that appeals to us, and, at the same time, engage those desires publicly, in the sense that we are consuming videos that are feeding us desire, and feeding that same desire to any number of unknowable others getting off on the same thing.

Productive as this reading of porn is, “Females” does some of its most compelling work by way of a rather unexpected close reading of the culture of the manosphere, those parts of the internet where disaffected men (incels and Proud Boys and others) go in search of ways to more authentically inhabit a masculinity no one actually possesses. (A “Chad” — manosphere argot for a popular guy who gets a lot of girls, and thus is the envy of sexually frustrated “beta” males — is based on a vision of a muscled, and confident football quarterback that is more the denizen of movie-screen high schools than any real locker room.) In these online forums, men effectively admit that they are not men in the ways they should be: they can’t get girls, they masturbate too much, they aren’t strong, they spend (ironically) too much time online rather than being out in the world making conquests. They want to be, in other words, anything but themselves, which Chu reminds us is being female; the manosphere’s “resentment of immigrants, black people, and queers,” she elaborates, “is a sadistic expression of his own gender dysphoria.” This cis-male dysphoria intersects with transgender identity when Chu notes that the “red pill” that appears in “The Matrix,” and which serves as the term for waking up from “feminist brainwashing” in alt-right discourse, has been seen as a stand-in for Premarin, one of the earliest testosterone blocking hormones, a reading of the film that Chu argues has been ascendant among trans women since director Lana Wachowski came out as transgender in 2012. The rage of the disaffected male, here dubbed his gender dysphoria (being female, but not wanting to be), gets channeled into acts of violence meant to prove that he isn’t what he is: “a beta [male] trapped in an alpha’s body, consumed with the desire to be female and desperately trying to repress it.”

There are implicit, and perhaps unanswerable, questions here. What if we could just accept that we are all female, that we are trapped by desires not of our own making? What if our desire to be desired were not somehow rotted from the inside by the cultural scripts that tell us we must be the top, never the bottom? This is the terrain of what is sometimes called “critical bottomhood,” a series of cultural arguments that attempt to free the receptive position (sometimes called “the female role”) from its typical associations with passivity and powerlessness, replacing them with new understandings of agency and control, as it were, from the bottom. What I take away from “Females” is a sense of the internal flaw of that line of reasoning. In seeking to turn bottomhood on its head, one is merely trying to avoid the “bottom” label; the transformation from bottoming to something like bottoming-as-a-kind-of-topping is just an attempt to reclaim an agency that we are told is what we should want, is what we should aspire to above all else.

While Chu can’t get us out of this trap, and in some ways languishes in this irresolvable what-to-do question in “Females,” her pointing to it is worthwhile. And so, whether we agree or disagree, Chu gives us much to consider.

This review originally appeared at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.