What College Students Can Teach Us About Beheadings and Our Own System of Capital Punishment

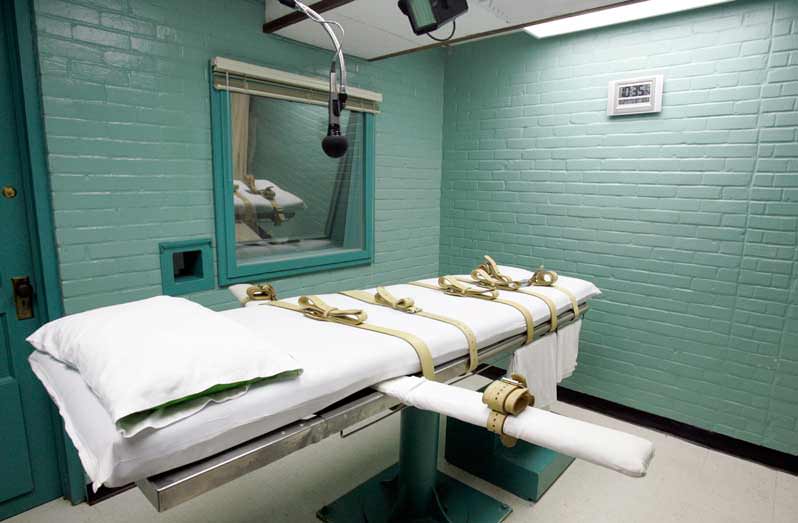

Last week, something happened to disrupt the Western superiority narrative of Middle Eastern beheadings, at least for me: I went back to college. The death chamber in Huntsville, Texas. AP/Pat Sullivan

The death chamber in Huntsville, Texas. AP/Pat Sullivan

Like everyone this side of a serial killer, I was repulsed by the videotapes showing the beheadings of captured American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff by a knife-wielding masked executioner of the Sunni jihadist organization that now calls itself the Islamic State. And like most, I was also moved by the dominant American narrative that both condemned the slayings and asserted the moral superiority of Western culture and the value we supposedly place on human life in contrast to the debasements and depravities promoted and practiced by the radical terror group.

But last week, shortly after news of the second beheading broke, something happened to disrupt the narrative, at least for me: I went back to college — not as a student, but to speak at a small undergraduate seminar on ethics and communication taught by Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer at USC.

I arrived on campus without much advance information about what we’d be discussing, told only that the class would be an informal gathering of no more than 15 students, and that I should just show up and be prepared to “schmooze” about my career in the law and as a writer. I had no idea until shortly before the first student poked her head inside the classroom that the topic du jour would be beheading. The students had even less of a hint.

Scheer began the class by reminding his charges that in their previous session they had examined conflicts between ethics and the law, and the fact that despite what we hear in the media and from our political leaders, the law often fails to live up to its ideals. And then he asked, point blank, “Does everyone know about the beheadings?”

The question at first was met with an awkward silence. This was a collection of juniors and seniors, mostly communication majors, all in their early 20s, racially diverse and, with one exception, female. They were accustomed to hearing and taking notes on their professors’ points of view. Now, they were being challenged to express their own views on an issue none had anticipated.

It took a long moment for all of us to focus, but slowly a full-throated discussion ensued about the death penalty and what lessons Americans might take from the killing of the journalists for their own system of capital punishment.

No one suggested the beheadings were in any sense justified or that as a method of execution, decapitation was anything other than gruesome, disgusting and unacceptable. “But if that’s true,” I asked, trying to earn my salt as a guest lecturer, “is there any ethical way for the state or those in power to take a human life?” I reminded the students that even with lethal injection — the preferred and purportedly more humane method used in this country’s recent executions — there have been reports of botched procedures in Oklahoma and Arizona, producing long and agonizing deaths.

To my surprise, the answers that sprang up around the room closely mirrored the classic debates on capital punishment that have long taken place in American courtrooms and society at large. Perhaps the death penalty is warranted for murder, one student suggested, invoking the “eye-for-an-eye” rationale of the ancient code of Hammurabi, and incidentally paralleling the current holdings of the Supreme Court, which restrict our death penalty to murder cases. Others, however, took the opposite position, arguing categorically that it was never proper for the state to kill, regardless of the manner of execution, once a prisoner has been taken into custody.

From there, the dialogue’s scope widened to take account of such factors as racial discrimination in the administration of the American death penalty, the absence of any hard proof that the penalty deters would-be killers, and the preponderance of poor and undereducated inmates generally among the more than 2.4 million held in our jails and prisons.

One particularly thoughtful student, reflecting on the beheading videos, suggested that our modern practice of performing executions in cloistered prison settings served to shore up popular support for capital punishment by removing its savage realities from public view. By releasing the videos for all to see, she reasoned, the Islamic State unwittingly might have done opponents of capital punishment in the U.S. a service.

Not everyone agreed that televising or otherwise turning American executions into public events (which they in fact once were) would be a good thing. But nearly all were receptive to another and even more important idea that is a feature of every system of capital punishment, whether enforced by hooded militants of the Islamic State or anonymous civil servants working for the federal government or for Texas or Florida or any of the other 30 states where the death penalty remains on the books. This is the concept of “otherness,” the notion reinforced by death-penalty regimes across the world and the organs of mass communication that serve them that dehumanizes those sentenced to die, removing the condemned both physically and morally from the larger community, rendering their executions not just acceptable but turning them into acts to be celebrated.

The day after the seminar, I thought about what our little group had accomplished, probing and exposing the hypocrisies and weaknesses of the dominant narrative of capital punishment and American exceptionalism. But as pleased as I was, I knew, of course, that our accomplishments were small and merely theoretical.

Across the country, there are still more than 3,000 prisoners housed on death row, waiting to meet their ends. An estimated 4 percent of defendants sentenced to death in the U.S. since 1976, according to a new study, have been innocent. Over two-thirds of the world’s nations have abolished the death penalty, but no sitting member of the Supreme Court has ever written in an official opinion that capital punishment in this country should be declared unconstitutional.

In the meantime, while our major news networks showcased the slaughtering of Foley and Sotloff, they blacked out a story that Saudi Arabia had beheaded an Iranian and three Syrians convicted of attempting to smuggle hashish, bringing the number of people decapitated the past month in the oil-rich kingdom to 30. The barbarity of the Saudis, our friends and close allies in the Middle East, apparently isn’t part of the dominant narrative, which only underscores the urgency to change the narrative and put an end to the death penalty everywhere, once and for all.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.