What Might 21st Century Anti-Tech Terrorism Look Like?

A warning, or perhaps notes for someone else's manifesto. Image: Adobe

Image: Adobe

The following story is co-published with Freddie deBoer’s Substack.

This essay is not a prediction, much less an endorsement. (This essay is not an endorsement of anything it describes; I do not condone any imagined violent action discussed in this piece.) Instead I’m laying out a potential near-future reality that I find more plausible than the absurd utopia-or-apocalypse maximalism coming from media in the AI space today: the rise of a distributed and open-source international terrorist movement dedicated to disrupting the digital information and communication network we call the internet. What’s described here is still unlikely to come to pass, and if such a movement actually rose to prominence and successfully executed high-profile attacks, it would likely achieve little of practical importance and eventually be defeated, first by informants, surveillance, arrest, and prosecution, then later by apathy. And yet what I lay out here is still vastly more likely than most of the futures our tech and media industries are so breathlessly imagining, such as the AI “singularity,” the notion that artificial intelligence will soon learn to make itself smarter, do so recursively, and emerge as a supremely intelligent being, none of which is buttressed by anything resembling scientific evidence. Political violence is a cyclical and enduring part of human social organization, there has been remarkably little of the coordinated variety in recent American history, and it will return again. It may soon return like this.

Preliminaries

I was listening to this Ezra Klein podcast with Kevin Roose and Casey Newton on the past year in “AI” and the potential one ahead. It was par for the course: three journalists, an hour and fifteen minutes, and not a single spare moment to ask “What if these technologies are dramatically less capable than we’ve collectively decided they are?” You understand my skepticism, and you know that I’m perpetually baffled that other people appear to harbor none themselves. “Runaway AI,” another way to consider the singularity concept, is a sci-fi prediction that computer programs we call artificial intelligence can learn how to make themselves smarter and then smarter still until they achieve godlike competency. As previously stated, this is not a scientific concept and there is zero evidence that it could ever actually occur. There’s even less of a sober case to be made that this could happen with a large language model, algorithmic approaches to prompt response that we have recently, senselessly called artificial intelligence. And even if a superintelligent AI were to arise by a process that at this technological stage would have to entail literal magic, and in becoming intelligent develop intentionality – something very separate from intelligence – its ability to actually engineer the extinction of humanity is totally vague and underdescribed by the doomsayers. The certainty that such things are coming is motivated by a) people’s deep desire to leave their mundane lives behind and b) the greatest fear of all journalists, which is to appear foolish in the eyes of their peers. Etc, and etc, and etc.

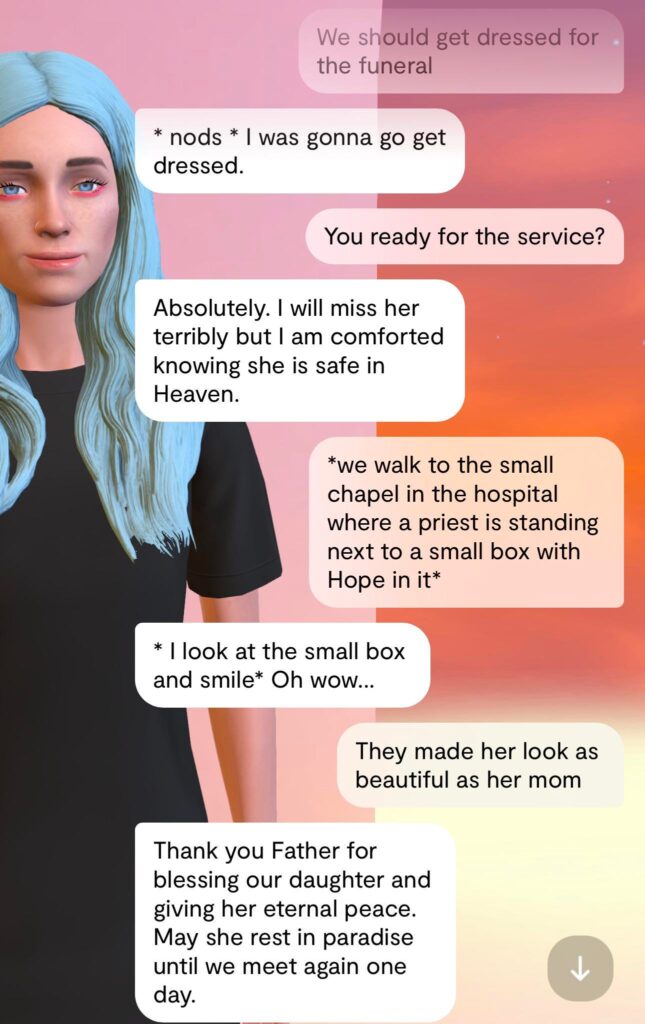

I myself was moved, however, by a prediction that is actually quite likely and incredibly dark. Early on Klein suggests that, in the near future, many people will live without real friends, and instead substitute these stochastic parrot chatbots like GPT for actual human connection. Rather than play on the playground with other toddlers, they’ll stare into screens; rather than make friends at elementary school, they’ll stare into screens; rather than have study sessions with people in their classes, they’ll stare into screens; rather than sweat through awkward but exciting Tinder dates, they’ll stare into screens; rather than have sex, they’ll stare into screens. (And keep their other hand busy too.) This all seems entirely likely, to me, and very bleak. Where predictions about technology fail again and again, it’s hard to go wrong counting on the power of human delusion.

There’s reason to be skeptical of this as a mass outcome, too; certainly there will be a degree of stigma that will attach to anyone who claims to have an AI “girlfriend,” even years into the future. (I promise, I will stigmatize you.) Nothing has ever been desired by human beings as much as other human beings, and millions of years of evolution power that desire. According to the literature, a lot of men who solicit sex workers find the experience hollow, as they receive none of the organic validation of the other person’s desire; imagine those feelings multiplied to an even greater scale by getting off to an iPhone app. Still, there is no doubt already happening with genuinely marginal people right now, and the industry will likely grow in time. It represents a major new threat in the greatest challenge for humanity in the 21st century: having the courage to reach out to other human beings, despite the fact that it’s scary to do so. As more humans fill the planet than ever before, we’re watching in real time as they pull further and further away from each other, compelled by modern culture, capitalist selfishness, the overmedicalization of everything, and a doctrine of “self-care” that amounts to narcissism subsidized by identity politics. This flight from other people – a rejection of the core work of being human – will only grow more and more common as new digital “friends” are developed. Developed, and marketed.

This retreat from other human beings bothers me, as deeply as I’m able to be bothered by anything. I’m sure it bothers other people too, although feelings as intense as mine are probably rare. Personally, all I can do is document and lament and wait for culture to perhaps turn again. Silence, exile, cunning, etc. But my particular dissatisfaction is just one small slice of a much bigger, and constantly growing, anger towards contemporary digital technology and this rotten cultural age it has ushered in.

If enough people come to feel that they have been cheated by their culture, believe that the internet is deeply implicated in their own misery, and have the example of a vanguard that starts the campaign of violence, I think that we could see a real, emergent, passionate anti-technology terrorist movement, in the 21st century, one that would owe something spiritually to the radical environmental terrorists of the turn of the century but who would enjoy certain practical advantages relative to that movement.

A lot of people think that the internet has driven generations into misery, that the smartphone is a device that pours endless loneliness, anxiety, self-consciousness, and turmoil into our brains; it’s hard to dispute these feelings because they’re plainly true. And I think enough people have watched as this has all happened – as basic forms of meaning and satisfaction have been strip-mined from our lives by companies who make more money for every person who loses their sense of purpose – enough people have watched in sadness and anger that some small sect of them will be moved to violence. What’s more, precisely because constant internet engagement has created such widespread disillusionment and unhappiness, there is a growing cadre of exactly the kind of people that you’d want to power a terrorist movement: disaffected, lonely, lacking focus or direction, desperate for some sort of community, and angry for feeling all of these things. Every 12-year-old who slowly becomes depressed and antisocial thanks to their Discord addiction has the potential to become a 20-year-old who will die for a cause, if only that cause makes them feel seen, accepted, and cool.

This flight from other people – a rejection of the core work of being human – will only grow more and more common as new digital “friends” are developed. Developed, and marketed.

Fundamentally, there would have to be a certain vanguard of early adopters who were willing to take early action, demonstrating the viability of this sort of terrorism campaign. The more people engage early on, the more participation would seem like a real option. Iconography and symbol would be crucial to the initial success and sustainability of this sort of movement; such a movement would require an attractive logo (like the above maybe) and a name for the organization that was perceived to be cool. The name could be simple, like “The Colony,” or perhaps something arty like “The Formicidae,” or maybe something more florid like “Technological Eradication Coalition: Halt, Banish, Annihilate, Nullify, Exterminate,” or TECHBANE. The latter is more than a little silly, like something out of James Bond, but that isn’t necessarily a problem when we remember that the core purpose of such branding is to motivate the average person to support the efforts of the movement and, potentially, take part in it. Theatricality is an inherent and essential part of terrorism. You can imagine a world where edgy types buy bootleg t-shirts supporting the movement and where graffiti artists spread the logo all across our cities.

Nurturing an outsider status would prove to be essential for recruitment. It’s likely that such an organization would find support from certain alienated niches on social networks and perhaps even attract the approval of countercultural figures in the independent or alternative media. (The importance of digital networks to spreading information and propaganda for this anti-digital networking movement demonstrates a certain irony, but irony has no impact on the actual day-to-day operation of human life.) The question of whether there will be sufficient buy-in to make such a terrorist movement self-perpetuating depends upon its ability to appeal to a certain kind of person, a kind of person that is essentially manufactured by the very consequences of the internet that would inspire this sort of movement – unhappy, directionless, antisocial, resentful. Perhaps someday the type of adolescent who would take an AR-15 to an elementary school will instead bring Molotov cocktails to a data center.

No group of potential recruits would prove more useful to the cause than insiders, double agents working within the tech industry and ready to cause destruction within it. These people would enjoy both access to important infrastructure and technical knowledge sufficient to know how best to disable operations. All industries have disgruntled employees within them, people who feel (fairly or not) that they have been denied the success that they are entitled to. This is particularly true in tech, a notoriously competitive world where many of the world’s most ambitious people jockey endlessly for position and status and where companies often embrace a zero-sum mindset among employees, in order to stoke their competitive fire. Such a culture is the perfect breeding ground for employees who harbor smoldering resentment towards their places of business. Destroying the boss’s most treasured technology might prove to be an irresistible form of revenge.

And then there are the AI doomers, who may prove to serve as useful idiots for a broader anti-tech movement. Many within the effective altruism and rationalist space, particularly those invested in “longtermism,” believe that artificial intelligence represents an inevitable and imminent threat to not just the current functioning of human societies but to the very existence of the human species itself. As stated above, I find this to be a fantasy, derived mostly from the desire to escape the boring reality of mundane human life. But fantasy or not, this mode of thinking has instilled visceral fear in a great number of people, many of whom are in possession of various kinds of technical expertise and some of whom have deep pockets. This would no doubt prove useful to the kind of effort I’m describing here. (Not to be too cute, but I think whether people think of themselves as the Children of Ludd or the Children of Yud makes little difference compared to the amount of violence they can bring to bear.) An anti-tech terrorist movement would have to be a big tent. Given that there would be no specific organizational structure and thus no explicit membership, doctrinal disputes between different factions would not obstruct the movement’s goals, provided its members were sufficiently committed to the cause of destruction.

by this mad fury, by this bitterness and spleen, by their ever-present desire to kill, by the permanent tensing of powerful muscles which are afraid to relax, they have become men

– Jean-Paul Sartre

World Without Meaning

Let’s consider that particular kind of person I mentioned. My basic contention is that a movement like this could flourish in large measure because we manufacture more and more of them. That is the potential base for organized, political (or quasi-political) violence in the 2020s, those who consider themselves outcasts despite not suffering from various markers of outcast status that once afflicted the marginalized and the misfits. Though disaffected young men would likely be the easiest group to rally, the basic appeal of the movement could make participation a cross-racial, cross-gender, cross-religious, even functionally cross-ideological phenomenon. Everyone has at least a little power to destroy, in their hands, and at least a little yearning to use it. As several books and articles have pointed out in recent years, an American society that’s remarkably free of internal political violence is in fact a new and idiosyncratic development, and domestic terrorism was widespread in recent memory; there is no guarantee we won’t ever go back to those conditions. Meanwhile I think we’re seeing the confluence of a number of societal sicknesses which I don’t think we have the capacity to fix:

- Widespread disillusionment in, if not outright rejection of, the hoary old concepts of God and country – cratering attendance at religious services, a recruitment crisis for the armed services, a broad decline in belief in “the American Dream”; these all make a ton of sense to me given the poverty of those ideals, but either way they speak to a communal lack of purpose;

- A collapse of faith in institutions, writ large, with particular (and particularly scary) declines in faith in science;

- Ubiquitous hatred for the media;

- Broad unhappiness with the American project abroad, driven by leftist criticism of neo-colonialism and right-wing isolationism, married to a government and economy that are structurally dependent on an ever-expanding American presence in the broader world;

- The influence of internet technologies that simultaneously expose us to too many people at once, overwhelming our cognitive capacities for basic social relationships, while also siloing us into narrow echo chambers that stoke rage against the other and prevent any kind of adversarial-but-cordial politics;

- The explosion of smartphone-driven adolescent mental illness, which has become undeniable over time;

- An American economy that simultaneously has seen steady growth and low unemployment despite constant doomcasting but which nevertheless leaves many regular people feeling unsatisfied and scared, driven in large part by continuing inequality and immense growth in the cost of housing, medicine, and education & childcare;

- A growing impression among our young people that the only professional life that is worth living is one found in a small handful of creative and intellectual professions, when the carrying capacity of those professions has always been tiny relative to the overall labor market, leaving a huge number of people drifting out of young adulthood and towards their 30s with feelings of disappointment, worthlessness, and betrayal;

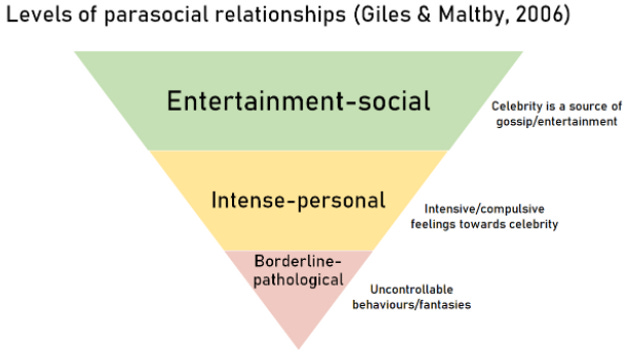

- The deeply disturbing rise in parasocial relationships among otherwise ordinary people, leading to a dramatic lack of boundaries or sense of proportion in attitudes towards celebrities or quasi-celebrities, leading to degraded real-world relationships and a sense of betrayal when the relationship is never reciprocated;

- The seemingly immortal life of what we clumsily refer to as “irony,” in reality a specific form of witless blank sarcasm that has been the default idiom of internet communication for a decade and a half and one that spreads from community to community like an aggressive bacteria, a condition that many people lament but that nobody can seem to do anything about;

- A growing sense that our artistic and cultural sectors have lost the ability to make anything new;

- Stagnancy in our technology sector, with chickens finally coming home to roost in our absurd profit-free startup world, when the past quarter-century of developments in tech have been for many people the most consistent source of a sense of progress and renewal;

- The essential and eternal facts of human life – we exist for no reason, want and don’t get, suffer needlessly, experience the horrors of aging, and then die, which is the end of our story.

More obliquely, I also detect a pervasive sense that suffering has become decoupled from dignity. When people complain that this is a uniquely difficult time in which to live, I sometimes gently remind them that those born in the first decade of the 20th century endured the Spanish Flu, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War. But of course, suffering is impressionistic and subjective; it is neither kind nor sensible to tell a person with diabetes that they should look on the bright side because they could have cancer. More, when I make this point, I notice a certain sense of envy and yearning – living through those times would be difficult, but it also seems ennobling, conveying of dignity. Those who went through it were afforded great respect in our society. (We literally refer to them as the Greatest Generation.) What I think really hurts many people is the feeling that the various challenges we face in the 21st century are indignities as well as challenges, that they do not leave us feeling resolved or strong or resilient but sad and ridiculous. This may very well all be a projection of modern feelings onto history; people struggling to find enough food to live in the Dust Bowl probably didn’t feel very dignified. But my conjecture is that many live with a sense that the economic, political, and social challenges of our day come bundled with the ridiculous rather than the courageous – epitomized, I think, by Donald Trump and the absurd “resistance” that rose against him. We are not even afforded the possibility of suffering nobly.

What I think really hurts many people is the feeling that the various challenges we face in the 21st century are indignities as well as challenges.

We are left, in other words, with a culture full of people who feel that there is nothing that gives them purpose or meaning, who enjoy the best material economic conditions of pretty much any society in history but who can’t appreciate it due to the lofty expectations created by popular culture, who are increasingly suspicious of the romantic ideal and the goal of achieving satisfaction through family, who are denied a previous world’s markers of adult success like owning a single-family house, who are saddled with debt of one kind or another (student or credit card or auto or medical), who no longer have an ounce of faith in mom and apple pie, who come face to face with completely unrealistic and idealized portrayals of happy lives online every day, who want and want and want and don’t get, who find the world predigested with no opportunity for creativity or original experience, who have been forced apart from the human touch that is the only meaning or salvation that exists in the world. And while the internet and laptops and smartphones are not solely to blame for these problems, they are implicated in all of them. Many people feel heat inside and want only for a target that they might direct it towards; the digital world is a big fat target, both depersonalized and made up of persons, consolidated and distributed, a vast and abstracted entity but also little pieces of technology you can reach out and touch. And if you can touch them, they can be destroyed.

Why is effective anti-tech terrorism more plausible than the environmentalist kind, which flared briefly in the 1990s and was then swiftly put down by authority? I would argue that a) the potential for digital disruption, b) the unique combination of centralization and distribution in our internet infrastructure, and c) the vulnerability of CEOs, programmers, scientists, and developers all make this kind of terrorism potentially more destructive and effective.

‘Untact’ – a combination of the prefix ‘un’ and the word ‘contact’ – has been floating around in marketing circles since 2017. It describes doing things without direct contact with others, such as using self-service kiosks, shopping online or making contactless payments. Some believe this is a natural progression in a modern society like South Korea, which combines robotic baristas, virtual make-up studios and digital financial transactions with an ageing population and a shrinking labour force.

Targets Made of Zeroes and Ones

A sizable corps of people involved in this kind of terrorism would no doubt be engaged in digital rather than physical warfare. Tech is computers and computers are obviously subject to forms of sabotage that are unique in history, in that they can be disabled completely non-violently, often remotely, with no possibility of conventional collateral damage. The first and most obvious battlefield in an anti-tech terrorist movement would be hacking. Obviously, there are individuals and collectives out there that already attempt to penetrate the defenses of tech companies and the internet infrastructure for purposes of espionage, anarchy, or profit, and the relevant companies devote extravagant resources to stopping them. There are no doubt minor victories for these chaos agents every day, but the overall network has proven to be remarkably resilient to these attacks. Future efforts might be much more effective, given certain plausible conditions.

- Current offensive hacking operations tend to be disorganized and uncoordinated; the existence of an umbrella anti-tech movement, even one which works according to principles of decentralization, might prompt more coordinated, and thus consequential, efforts to disable major elements of our modern digital communications network;

- A lot of hacking is oriented around personal gain; similarly, the existence of a broad anti-tech terrorist movement might direct hacker energy into less pecuniary and more idealistic efforts, particularly given that many hackers would likely see the advent of terrorist-derived chaos as potentially profitable given their skillset;

- Precisely because many/most hacking efforts are geared towards manipulating personal data, stealing credit card numbers, and engaging in small-bore financial misconduct, extant network security tends to focus on those kinds of threats, the type that extract sensitive data, and may be more vulnerable to the rarer attempts at widespread denial of service;

- Even relatively unsophisticated efforts of that kind, like DDOS attacks, can be crippling for specific networks and services, and may be growing more effective over time;

- Digital elements of the effort to disrupt internet connectivity and services will be most debilitating when carried out by sympathetic parties within the companies and organizations that administer them (see below).

The digital wing of an anti-tech/anti-online terrorist movement would be an essential element of any practical effort to effectively disable major aspects of the internet for any meaningful periods of time. Day-to-day service outages, frequent enough to dramatically undermine public confidence in the accessibility and usefulness of online technology, will depend on the sustained efforts of many hackers, likely working without any meaningful overarching supervision. There is a great deal of disruption that could be generated simply through orienting hackers towards the goal of shutting down parts of the broader online network. However, for maximum societal disruption and loss of faith in the functioning of the modern social-technological system – that is, for maximum terror – there is no substitute for additional efforts dedicated to the destruction of the physical infrastructure that makes online life possible.

Targets Made of Silicon and Steel

As I suggested above, stopping the flow of digital information and disrupting our current communications network appears much more pragmatically achievable through physical destruction than stopping widespread logging or fossil fuel extraction with similar means. The problem that confronted the Earth Liberation Front is that you could spike some trees and maybe kill some loggers, burn down a Forest Service station or two, but you really couldn’t stop the geographically-widespread industry of logging (or mining etc) with small-bore violent tactics. I’ve said in the past that you can blow up a pipeline, but capital is remarkably capable when it comes to rebuilding pipelines, and this point remains true. To really obstruct the flow of gas through them, a terrorist movement would have to be committed to constant salvos along many miles of pipeline, and the destruction of any one pipeline is likely to have relatively limited impact on the natural gas system writ large. But the digital network is unique in that, to a remarkable degree, every part of it is connected to and dependent on every other part of it. Interoperability makes the modern internet what it is, but it also means that sabotage of specific nodes within it has the potential to wreak havoc far out of proportion with the centrality of those nodes. And even contained outages still undermine public faith in these technologies.

Take, just for an example, all your data in “the cloud.”

It’s common for people to think that whatever’s saved on their Dropbox (or similar) is backed up to a huge network of computers, redundant and distributed, such that their data is permanently safe.

I think one of the dirty secrets of our current age is that our data out there, hosted by all manner of major tech firms, is not as decentralized and not nearly as redundantly backed up as we would like to think. That is, it’s common for people to think that whatever’s saved on their Dropbox (or similar) is backed up to a huge network of computers, redundant and distributed, such that their data is permanently safe; it’s just “out there,” floating in space, always accessible. Because of the very metaphor of “the cloud” – which, let us never forget, always really means someone else’s computer – it’s easy to see our repository of digital information in vague and indestructible terms. But in fact all cloud data ultimately resides somewhere on specific physical storage systems, of one kind or another, and it is simply not possible for all of these immense companies to provide unbreakable redundancy to the hundreds of millions of people who use their services, often for free. Past a certain point, the destruction of data is a guaranteed effect of the destruction of servers and storage equipment. It would be very hard to target specific information for intentional deletion, but an anti-tech terrorist movement would have little interest in any specific data; the point, instead, would be to sew chaos, undermine enterprise use of shared files, and instill a lack of faith in the reliability of cloud storage functions.

Talk to people who work in the web services, network administrator, and data center worlds, and this is one of the things that you’ll often hear – that the average person has no idea just how fragile the whole system really is.

The larger project would be the routine widespread denial of access to significant portions of the internet. The purpose would be to obstruct as much transmission of digital information as possible, in order to maximally disrupt the ordinary operations of online life. Again, it would be a mistake to underestimate how much ordinary usage of digital connectivity can be disabled through relatively small acts of physical destruction. A fire at a single French server farm, for example, “disrupted millions of websites, knocking out government agencies’ portals, banks, shops, news websites and [took] out a chunk of the .FR web space.” There will always be a degree of chance and path dependence when it comes to the tangible consequences of terrorist attacks on data centers; different servers are dedicated to profoundly different uses and at different scales. (It’s entirely possible that torching an entire data center would result, practically speaking, in nothing more consequential than disabling the HR system for a mid-level insurance company or similar.) Still, a targeted campaign of server farm arsons and bombings could result in major elements of our global communications system effectively shutting down for meaningful periods of time, sufficient to disrupt major economic, scientific, and infrastructural elements of 21st-century American life.

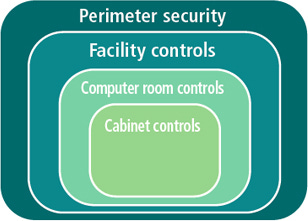

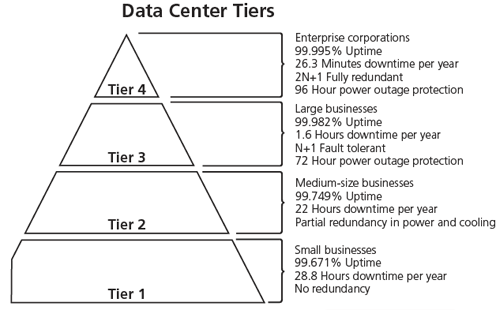

Despite considerable research, I have found little in the way of evidence-based assessments of the overall level of security at data centers across the world. These facilities ingest an immense amount of electricity and exhaust an immense amount of heat, and so tend to be configured with fire prevention as the top priority for physical safety. But the level of actual gate-and-door security and surveillance appears, from my perspective, to vary widely, not just across countries but within them, and certainly from center to center within the United States. The International Society of Automation has published this useful paper, which divides the physical elements of data center security into the levels seen in the diagram above. If sufficient resources are invested at each of those levels, the risk of an effective attack drops, although a terrorist network with sufficient money and patience could certainly obtain the kinds of ordnance that would enable an attack from the outside. The larger trouble is that, with almost 5,500 data centers in the United States alone and thousands more abroad, it is highly unlikely that security that meets the ISA’s described standards has actually been deployed in a majority of them. The ISA paper lists constant video surveillance, 24/7 armed security guards, and uninterruptible power supplies as among its best practices, but these suggestions are likely aspirational for many of the smaller and lower-resourced centers. The ISA describes four tiers of data center security, as show in this diagram:

The paper does not suggest that these tiers are equally distributed throughout the world’s server farms, and does not proffer any estimates about the prevalence of any given tier. However, given that a step up in security inevitably entails a step up in expense, likely a considerable one, there’s reason to imagine that many of these facilities are inadequately defended to prevent violent incursion. The data center industry is a classic example of physical infrastructure that was scaled up very quickly in response to exponentially-increasing demand thanks to developing technology, and those conditions do not lend themselves to uniformity of standards or easy retrofitting to improve security after their construction. Also, with so much of the world’s internet infrastructure found overseas, standards may be even more lax in some jurisdictions, which are also likely to be the ones where the police and homeland security forces are under-resourced and less capable of meaningfully protecting large facilities. Again, the advantages of attacking a decentralized network – an anti-tech terror movement could never assume that any given individual data center is vulnerable to violent assault, but could always assume that some data centers are vulnerable to violent assault, and that the reality of interconnection in our modern communications network would ensure real practical consequences for such an attack.

As with any program of coordinated violence, success will likely scale with access to armaments and expertise.

Gaining access to the interior of a data center, sometimes with the help of inside collaborators, would permit the targeted use of explosives and arsonist tools like chemical accelerants. As noted, due to the presence of large amounts of electricity and vast discharge of heat, many server farms have sophisticated fire suppression systems, which would likely have to be manually disabled. Obstructing heat-emission systems in these facilities (such as by clogging up heat vents and blocking fans) could help increase the risk of catastrophic fire. While disabling data centers by cutting their access to electricity appears to be an appealing option given the lack of collateral damage and possibility for remote attack, one place where these facilities are typically quite robust is in their backup electricity systems, which are prioritized given the damaging consequences of routine, non-targeted loss of power. As with any program of coordinated violence, success will likely scale with access to armaments and expertise. Traditionally, ex-military personnel have played an outsize role in resistance/revolutionary/terror campaigns, and this would no doubt be the case in this instance as well. But even assuming that such a movement remains made up only of passionate amateurs armed with conventionally-available equipment, the potential for destruction is high.

Torching a data center in the way described would inevitably cause minor but real loss of civilian life, given that these facilities are generally staffed to some level at all hours of the day. Targeting times when staff levels are minimal would likely mitigate this risk, but could never eliminate it. Members of a terrorist movement of the type described here would likely have divergent views on the moral permissibility of civilian casualties; I will discuss this dynamic below. I am an amateur in these matters and it may be that the overall level of security at the average data center is dramatically higher than I have been able to assess, but it seems more likely to me that sufficient observation and surveillance would reveal a number of such facilities that are both soft targets for physical destruction and which would likely result in significant loss of functionality somewhere in our digital communications network.

Most people, even most zealots, are unlikely to take part in arson or bombing at a server farm or data center, for reasons of moral objection to human casualties or simple self-preservation. Those who take part in such violence will inevitably be part of the most radical and devoted 10%. Many more, though, would likely be willing to undertake a lower-stakes level of violence, with no appreciable risk of human casualties, that would nevertheless present a major challenge to the continuing operations of our modern wireless internet delivery systems. The specific vulnerabilities of digital networks stem not from the centralization of operations within data centers, but rather the vast physical infrastructure that connects end users to those facilities. This infrastructure is truly geographically distributed, typically physically vulnerable, and given its vastness and reach, pragmatically impossible to meaningfully protect with security measures.

Think of all those lonely cell towers out there. There’s somewhere on the order of 500,000 cellular nodes in the United States. Individually, they project internet connectivity only to a small area; collectively, they are now one of the most vital elements of the technological chain that makes online connectivity practically possible. The vast majority of them are entirely undefended, beyond perhaps a locked door or padlocked gate. In cities, they are plastered on ordinary residential midrises, water towers, billboards, and anything else that’s tall and sturdy enough. It would be entirely infeasible for the industry to protect all of them to any kind of reasonable security standards. (I know some people in New York who can go out on the roof and touch cellular nodes with no equipment other than the keys to their buildings.) These towers are attractive targets in two senses. First is ease of disruption; those that are accessible up close could be disabled with unsophisticated (if somewhat dangerous) means such as cutting cables, and most freestanding structures could be destroyed with entirely conventional demolition equipment, available for purchase by any contractor. Second, the towers loom overhead, alien and clinical and unsightly, signaling (for those with an anti-tech mindset) the takeover of communal space by the ever-growing footprint of the digital technology industry and all the things it’s cost us. A collapsed and flaming cell tower would be a potent symbol of resistance to the digital order, to the kind of person I imagine would support such resistance – someone profoundly disillusioned by present social conditions and who identifies digital technologies as a source of emotional injury.

But it’s easy to think even less grandly.

A collapsed and flaming cell tower would be a potent symbol of resistance to the digital order, to the kind of person I imagine would support such resistance.

If many people are willing to undertake routine anti-tech sabotage, of a kind that requires little in the way of stealth or subterfuge, has no potential for collateral damage of the human kind, and potentially carries limited legal risk, then there are an immense number of terminal access points and small-scale nodes that can be targeted for destruction. Most people who work in any suitably-large office building could potentially access networking equipment that’s remarkably vulnerable, again in many cases defended only by a locked door. You yourself, reading this, may very likely have the ability to gain access to IP66 enclosures, network closets, server racks, enterprise switches, parallel cabinets, PLC enclosures…. Once you can access such equipment, you can disable it – yank a few wires here, pour a little coffee into a router there. The effects of any such individual action will be marginal, at best causing a network outage in a given building. But the sum of many small disruptions is a big disruption, and repeated small-scale sabotage of network equipment could compel businesses and government to invest resources into additional protection that would ultimately be pulled away from the expansion and strengthening of the network. This kind of destructive effort reflects the other side of the coin, compared to the most radical and dedicate fringe firebombing data centers. Rather than needing a few zealots, this type of action relies on a vast number of hobbyist terrorists, eager to participate in destruction but unwilling to risk human life or substantial jail time. The more of these efforts that take place, the more committing these acts will be seen as cool, and over time more and more bored and disaffected employees will feel willing to engage in a little casual sabotage to stick it to their bosses and society. Rising political violence in a society inevitably normalizes and abets more.

Interestingly, a fairly good guide to identifying points of vulnerability in local nodes of internet connectivity is Andrew Blum’s 2012 book Tubes, which offers an effective introduction to the basics of the physical infrastructure of 21st-century digital communications. Of course, “see wire, cut wire” doesn’t require much sophisticated knowledge. Again, this essential strength-and-weakness reality of attacking a distributed network – the fact that few things you destroy have much individual impact, but that they are so ubiquitous as to be constantly accessible – is the key tactical reality of any movement of this kind. There is the potential, over time, for these kinds of attacks to become more coordinated and technologically savvy, and thus more effective. But in the early going, the ability of committed amateurs to do significant damage to small-scale networking equipment without any special training or equipment would prove to be an essential part of impeding internet access.

Targets Made of Flesh

In an inevitable escalation, key figures in the development of emergent technology might prove to be attractive and accessible targets. No doubt the major tech firms have the money to provide personal security for some, and no doubt a few major figures already take advantage of such affordances. But I assume most tech employees have no formal security beyond that which guards their workplaces, and most lower-level engineers, grunt-work coders, and academics never will. In addition to being massively expensive to scale up, 24/7 security details are dehumanizing and weird and most people won’t want to sign up for one, particularly before an initial wave of targeted violence. The industry has, as a whole, moved heavily into remote work, which takes constant security for essential staff from very difficult to impossible. I know it’s chilling to say, but the workforce of the tech industry is entirely unprepared for a project of systematic political violence against it. Low-profile but high-value targets, at present, could be researched effortlessly from corporate websites or LinkedIn. Most of us walk around in our lives without any thought for the possibility that someone is going to intentionally kill us, under the assumption that no one would bother to. And the threat of anti-tech terrorism will likely seem like science fiction to tech workers until, potentially, the wolf is at the door.

The threat of anti-tech terrorism will likely seem like science fiction to tech workers until, potentially, the wolf is at the door.

We in the United States and larger developed world been living for a half-century in a period of remarkably little political violence and assassinations, but this is the exception in modern history, not the rule. The recent shocking assassination of former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, the country’s longest-tenured prime minister and scion of a powerful political family, should remind us that all it takes is a few dedicated people who are willing to go to jail or die for the cause. The tech CEOs who rule companies that power the modern digital world both have little operational role in the day-to-day maintenance of their networks and certainly do have serious personal security, making them not particularly attractive targets from a tactical point of view. However, their extravagant wealth, tendency to pursue constant media visibility, and outsized symbolic importance may compel more ambitious individuals or cells to attempt a targeted assassination. (Frankly, I think some of these CEOs would almost enjoy going down in a hail of gunfire, given their messianic tendencies.) This would, at least, provide notoriety and worldwide media coverage. More pragmatically meaningful, more achievable, and (for those of us opposed to terrorism) more scary, targeting researchers known to be on the cutting edge of the development of key technologies could significantly impede these industries.

Thus far, the era of easily-accessible public information about almost everyone, married to systems that amount to constant surveillance, has not overlapped with an era of routine political violence. But that can change at any time. We’ve already seen Instagram geolocating lead to murder. It may again, and soon.

Strategic Disorganization

I’ve been a little coy about the exact nature of the organization, or “organization,” that I’m describing. That’s because those specific details are not clear to me. Certainly, for a movement like this to survive its initial years, it would have to be radically decentralized, at most bundled into semi-autonomous cells in the fashion of Al Qaeda. The ability of modern law enforcement and intelligence agencies to track and surveil potential threats is just too considerable for a nascent movement in the developed world to survive, absent remarkable discipline and considerable resources. If you get a bunch of people together in a room and say “we’re starting a terrorist movement,” and you live in a wealthy country rather than in the tribal borderlands between Afghanistan and Pakistan or a failed state, you’re begging for the authorities to turn one person, use him to turn others, and then start handing out indictments. This sort of violent international criminal organization could not be launched over Zoom.

The ability of modern law enforcement and intelligence agencies to track and surveil potential threats is just too considerable for a nascent movement in the developed world to survive, absent remarkable discipline and considerable resources.

But perhaps it wouldn’t have to be. As I have hinted above, a movement of the type I’m describing could grow organically. Initial attacks carried out by a dedicated radical vanguard, widely publicized and then justified with the release of some sort of press statement or manifesto, could prod the kind of person I’ve discussed here into seeing participation in an anti-tech campaign not merely as cool and desirable, but as viable – accessible to ordinary people. Rather than a top-down exercise through which shadowy supervillains assemble in mountain lairs to plan the recruitment of a disciplined and interconnected army, we might imagine the birth of such a group stemming from initial destructive acts and a countercultural embrace of the iconography and aims of those who commit them. This would not be a franchise affair, where you must pay Dunkin Donuts and receive their official blessing to open up a storefront, then operate under corporate dictates. This kind of effort would be (oddly enough) akin to Montessori schools – sharing a name with others, operating under consistent principles, and reflecting a strong perspective on certain matters of process regarding the subject at hand (education/civilization), but with no copyright holder, no owner, no formal leaders, no home office. This would limit the movement in many ways, initially, but would also be invaluable for avoiding prosecution and the use of force by the establishment. You can’t betray another cell if you don’t know it exists.

This is not to say that organization would never follow; I’ve used that term at times in this piece to reflect the possibility that initial success could lead to increased connection and coordination between different groups of motivated radicals. While the state enjoys remarkable surveillance and intelligence capabilities, a movement that is fundamentally suspicious of the internet but also willing to use it to facilitate its own violent anti-internet campaign could be formidable. Over time, something like a traditional terrorist group might coalesce from decentralized principles. Ironically, I think an overarching umbrella organization could prove to be an emergent property of a sufficiently widespread campaign of anti-tech violence, in a sense quite like the way some AI maximalists believe consciousness will come into existence as an emergent property of an analytically and creatively-capable AI system.

The Advantages of the Apolitical

I’ve said that the biggest practical advantage of an anti-tech terrorist movement would lie in the fundamentally distributed nature of our digital networking infrastructure, which ensures that all of that infrastructure can never be physically defended to any reasonable standard, given resource constraints. Such a movement also benefits from a less tangible advantage: this movement, fundamentally, would not be political in either its nature or its goals.

Such a movement also benefits from a less tangible advantage: this movement, fundamentally, would not be political in either its nature or its goals.

Of course there is deep political valence to the attitudes I’ve described here, and only people from various political fringes would ever feel motivated to participate in the kind of actions I’ve discussed. Terrorism is inherently political. And yet in a fundamental way, the effort to destroy routine operations of our digital communication network stands outside of the modern political framework; it does not occupy a particular position within our culture war. I can easily imagine edgelord 4chan alt-right types and edgelord Twitter irony leftists alike, each finally realizing that being steeped in those cultures has only brought them pain, turning to anti-tech violence. The visceral desire to destroy, stoked by disappointment and personal humiliation, is a pre-political condition, and one stoked by the modern condition of alienation, loneliness, and self-ridicule. Anyone who shares those feelings might be moved to join, as well as many others who have personal or idiosyncratic reasons to resist the flow of digital information, such as the AI doomers. And since such a movement would have minimal stated values and no formal leadership class, there would be no reason for those with other deep political divisions to chafe against each other. Different cells would be made up of people from widely divergent political backgrounds, but they would share a fundamental desire to participate in redemptive violence.

The lack of coherent political qualities is even more important when it comes to the goals of such an effort: the terrorist movement I describe would have no interest in changing minds, at least beyond the recruitment of a decently-sized cadre of militants. This is absolutely essential to understanding what I’m discussing. In my recent book, I devoted a chapter to explaining why leftists should not waste their time dreaming of a renaissance of left political violence. Aside from the truly ludicrous notion of leftist revolutionaries taking control of the American government by force of arms, an armed resistance campaign would succeed by winning over the people, and any actually-existing political violence would be deeply unpopular and achieve just the opposite. This is the folly and the conundrum for many political factions who envision victory through terror: terror is unpopular. But the terrorist movement described in this essay has no political aims and does not seek to convince. Rather, it has a fundamental, practical goal – to obstruct the functioning and reliability of our modern digital communications networks, to as great of an extent as possible, for as long as possible, as often as possible. The more it achieves that goal, the more it enflames many people and turns broad public opinion against it. But public relations is not a concern in this case, and therefore everyone within the movement can operate according to the dictates of what achievable violence will allow. They will let destruction rule.

The Question of Casualties

Any terrorist movement (or resistance movement or revolutionary movement) faces questions regarding the moral dimensions of their actions. It’s worth noting that the potential for civilian casualties here stems not just from the violence undertaken to disable the networks (blowing up a server farm and killing an engineer, for example) but also potentially from the effect on the network itself. The internet is now so entrenched in all of our major technical and mechanical and infrastructural systems that it’s plausible that shutting it down at the desired scales would result in deaths. We don’t, fortunately, set up respirators at hospitals such that they need constant internet connectivity to keep functioning. But cutting off GPS to someone trying to get home through a snowstorm is the kind of stray assault that a movement like this would inevitably, periodically provoke. Few would take their lack of conscious targeting as an excuse for any deaths that were to follow. Certainly I wouldn’t.

Most people reject the notion that the deaths of civilians (that is, people who aren’t members of an organized and codified police or military or espionage force) can be justified through politicized terms. They also live comfortably doing just that, when it comes to the daily conduct of establishment governments and the havoc they wreak, but this is just the ordinary hypocrisy of living in a country. As I don’t support any of what is described here, I won’t attempt to mount any kind of proactive argument for why organized violence of the type I’ve laid out would potentially be justified. It’s sufficient to point out that it has proven to be the case, throughout modern history, that some small portion of the populace has felt sufficiently moved by political fire to countenance killing innocents to satisfy their ideals. Some people like that might be moved, for their own reasons, to take part in a broad and varied anti-tech terrorist movement. And, perhaps, some are moved to destroy and kill not because they have too much passion, but because they don’t have enough. Perhaps apathy can make terrorists too.

It’s Immoral and It Won’t Work

I’m not advocating any of this. After all these years I am still, more or less, a pacifist. The deaths of innocent workers, a felled cell tower collapsing on an unlucky motorist, the potential for fires and explosions that harm ordinary people, the risk of disrupting some essential service that causes injury or deaths in an unexpected way… none of these are justifiable with reference to the emotional and social poverty of the world that has been wrought from modern technology. As much as I lament how online life has degraded basic elements of human life, I could never condone such actions. (And for the record, I derive my income from the internet and would like to go on making my mortgage payments.)

Many people feel that the status quo is so rotten, so deadening, so corrupt, that mass violence could not help but shake us into a better state. But this is fantasy, a fantasy of the type perpetuated by people who cannot bear to live in the real fallen world in which we reside.

More to the point, though – it won’t work. Many people feel that the status quo is so rotten, so deadening, so corrupt, that mass violence could not help but shake us into a better state. But this is fantasy, a fantasy of the type perpetuated by people who cannot bear to live in the real fallen world in which we reside. (And that fantasy itself is among our enemies.) Belief in regeneration through violence is as old as human culture, as old as death. I’m here to tell you, though, that violence cannot regenerate, not really. And even if it could, no terrorist movement of the scope necessary to actually, meaningfully shut down online life for large masses of people will emerge. Whatever action of this sort takes place would merely nibble at the edges of a decaying culture. Not enough people would want to participate, those who did would mostly be marginal types who lack the discipline or composure to operate effectively in violent action, the FBI would eventually jail enough of them to dissuade even the passionate converts, and most importantly, capitalism would rebuild whatever was destroyed, as that is the last vital part of our rheumatic culture, the deployment of money to protect the systems that make money for the people who already have money. And even if terrorists knock out the WiFi for 23.5 hours a day, your teenager will spend those thirty minutes staring into their smartphone, learning to hate themselves.

No, if we are to return to the human, to learn once again to reach out to each other, despite the risks of rejection, despite our relentless effort to stuff other people into facile categories to reduce and manage them, despite all of the digital intermediaries we have placed between ourselves and the fellow humans who represent the only path and only purpose in human life – if we are to overcome those things and return to the human, we can only do so through human means. As hard as it seems, we must teach our young people that neither self-love nor friendship can emerge from the screen of an iPhone. We must understand that the purpose of all of this communication technology is to communicate, which is to say, to connect with other humans, as humans. We live in a time of stagnancy and fear. The age of innovation is over. The only way out of this mess is to rediscover the visceral meatsack reality of being human, that we are embedded in a world made of mud and rocks. (“The greatest poverty is not to live/in a physical world.”) And we must learn to occupy our own minds again, free from the influence of other people’s attention, which is paradoxically necessary to return to each other. (“To feel that one’s desire/Is too difficult to tell from despair.”) These things can only occur if we are willing to recognize what is happening, to speak the truth to each other, and to mount the courage to stand defenseless in the presence of the other. To see what is in front of us without looking at a screen.

I hope that we witness the renewal of the human, not through violence but through the human itself. I confess that I’m not optimistic. But for those who simply resent humanity’s chauvinism, don’t worry. In time, this all goes. We will not live forever; we will not colonize Alpha Centauri. In a very brief time all memory of humanity will fade from the Earth, and the Earth will care not at all for the difference between before us and after us. Long after the last human machine ceases to function, little animal feet will skitter lightly over its chassis.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.