RBG: Woman, Jew, Mother, Justice

For Women's History Month, we review a book on the extraordinary life of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

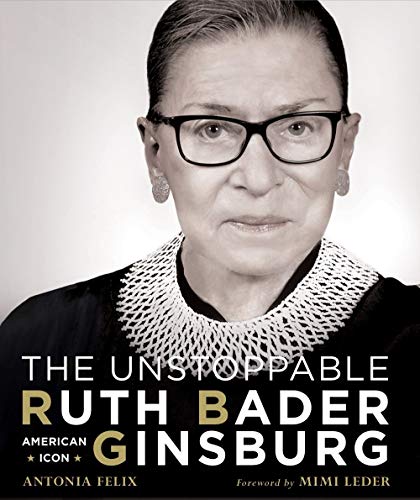

“The Unstoppable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, American Icon”

A book by Antonia Felix, foreword by Mimi Leder

Any book about Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg will be notable simply because she is remarkable.

Antonia Felix, a biographer, and Mimi Leder, a film and television producer, authors of “The Unstoppable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, American Icon,” have created a wonderful opportunity for readers to get to know Ginsburg through her own reflections on her life.

These authors drew upon and compiled a variety of Ginsburg’s presentations, arguments and other materials not normally published, to give the reader a unique insight into the mind of this extraordinary justice.

Born Ruth Joan Bader on March 15, 1933, the second daughter of Russian immigrants Nathan and Celia Bader, she grew up in a low-income, working-class neighborhood in Brooklyn.

Separate chapters take the reader from Ginsburg’s early years, detailing her frustrations at being discriminated against as a woman, and following her growth into the stalwart justice we see today. Throughout the book, Ginsburg refers to her mother’s guidance; she notes that “my mother told me two things constantly. One was to be a lady, and the other was to be independent.”

Her mother worked in a garment factory to help pay for her brother’s college education. At the same time Ginsburg studied hard in high school to win a spot at Cornell University. Her mother never saw her daughter graduate from high school with honors, or go on to be an attorney: she died from cancer the day before Ginsburg’s high school graduation. School personnel delivered Ginsburg’s honors to her at home, the next day.

During Ginsburg’s years growing up in Brooklyn, the values of Judaism were stressed as guidelines on how to live her life. She followed the dictums to work hard and achieve through study. She often tells about the Hebrew letters of the command from Deuteronomy: “Zedek, Zedek tirdof.” “Justice, justice shalt thou pursue.” In a speech on dissenting opinions she gave at Ahavath Achim Synagogue in Atlanta, she reflected on the Jewish artwork in her chambers.

She met her husband, Marty Ginsburg, on a blind date as undergrads at Cornell, when she was 17 and he was 18. “He was the first boy I ever knew who cared that I had a brain. Most guys in the ’50s didn’t,” Ginsburg is often quoted as saying.

Ginsburg reflected on college women, saying, “One of the sadnesses about the brilliant girls who attended Cornell is that they kind of suppressed how smart they were. But Marty was so confident of his own ability, so comfortable with himself, that he never regarded me as any kind of a threat.”

Ginsburg earned her bachelor’s degree in government from Cornell in 1954, finishing first in her class. She married Marty, who was then a law student at Harvard, that same year. Life was challenging for the young couple in 1954. Marty was drafted into the military and served for two years; after his discharge, the couple returned to Harvard, where Ginsburg also enrolled.

Then Marty received a diagnosis of testicular cancer and was given a dire prognosis. Ginsburg managed the household while her husband was in treatment. Ginsburg helped him with school by getting notes from his classmates, and cared for him and their baby while keeping up with her own classes.

After recovery, Marty went into tax law in New York, so Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School to be with her husband.

At Columbia she was tied for the top of her class, but no one would hire her. She has been candid about the ’50s not being kind to professional women.

She reflected on the three strikes she was up against: “In the fifties, the traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews,” she wrote. “To be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot—that combination was a bit too much.”

Finally, she landed a faculty position at Rutgers Law School, which was known to be more progressive than most schools; thirty years later, Rutgers Law would name its great hall in honor of the justice. She returned to Columbia Law as its first tenured female professor. She became a litigator for women’s rights, arguing a number of landmark cases in that domain that changed the lives of many.

She joined the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) while at Columbia University School of Law in 1972, and co-founded the ACLU Women’s Rights Project. The discrimination and barriers she faced as a woman, mother and a Jew propelled her drive as she handled groundbreaking cases through the 1970s, always keeping the calm, steady “lady’s composure” her mother had instilled in her. She earned the name “steel butterfly,” and, after a strong dissent on the Supreme Court, she also became known as the “notorious RBG.”

She was appointed by President Carter to the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1980. In 1993, she was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Clinton.

Ginsburg saw the opportunity to serve on the Supreme Court as a privilege and calling beyond any other. In a speech before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, in Washington, D.C., she stated her deep feelings on being a justice: “Some of you asked me during recent visits, why I want to be on the Supreme Court. It is an opportunity, beyond any other, for one of my trainings to serve society,” she said. She fervently believes that in her lifetime, she expects to see three, four and perhaps more women on the high court bench: “Women not shaped from the same mold, but different complexions.”

The book takes a look behind the scenes of the court to share with the reader the backroom formalities among the justices. Before each day in court begins and before each discussion, as they enter the Robing Room, they shake hands, all nine of them shaking hands with one another for a total of 36 handshakes.

In 2007, she spoke about the process of logging a dissenting opinion, which, she believes is critical to the ultimate result. Her experience taught her that nothing is better than an impressive dissent to improve an opinion for the court. She states that a well-reasoned dissent will lead the author of the majority to refine and clarify his or her initial position.

In a speech to a group of new U.S. citizens, she recalled the words of our Constitution’s beginning: “We the people of the United States,” as it sets out to “form a more perfect union.” Even though those early citizens were white, property-owning men, she reflected that that finally changed over the years to include people who had been held in slavery, women and Native Americans. She embraced her new fellow citizens as fitting the mold of those who came before them and helped to make America a more vibrant country.

“The Unstoppable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, American Icon” is filled with photos, drawings and quotes that give the reader a rare look inside Ginsburg’s psyche. The editors are clearly enthralled with their subject, and accomplish their goal of providing readers with a visual journey through her life, as well as a window into her inner thoughts and beliefs on the law.

To have Justice Ginsburg on the highest court of the land in the United States is a gift for those who seek justice for all.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.