Woody Guthrie’s Shack Becomes a Shrine

An interview with Ellen Geer about her actor father, the Red Scare and growing up with a famous folk singer in a cottage that’s now a museum. Woody Guthrie's former cabin and home to "The Shelter," a new museum opening August 3rd to honor his legacy. Photo by Ed Rampell

Woody Guthrie's former cabin and home to "The Shelter," a new museum opening August 3rd to honor his legacy. Photo by Ed Rampell

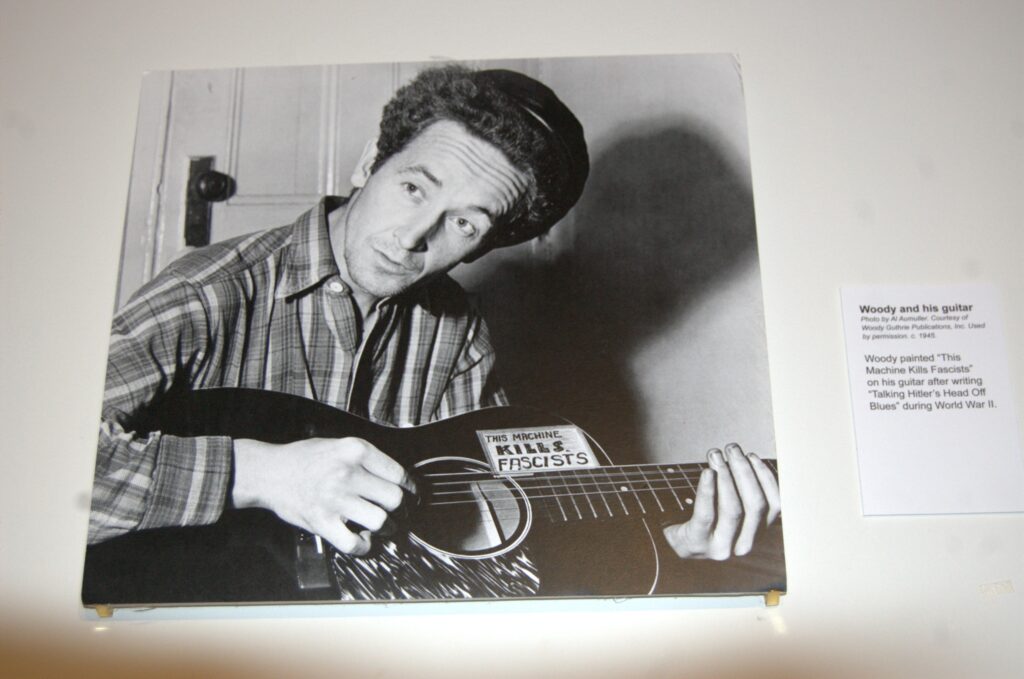

On Aug. 3, singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie is being doubly honored at L.A. County’s Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum, a 300-seat amphitheater north of Malibu. The Oklahoma-born composer — author of This Land is Your Land and inspiration to Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen and more — is being posthumously given a humanitarian award at his former one-room cabin, which will also be officially opened as a museum called the Shelter. It will house lyric sheets, artworks and photos of other musicians who performed there, including Pete Seeger, Odetta and Earl Robinson.

The Shelter will also feature photos from the films of Will Geer, who owned the house until his death in 1978. Born 1902 in Indiana, Geer is best known for his role of Grandpa Zebulon Walton in the beloved 1970s TV series The Waltons, as well as roles opposite James Stewart in 1950’s Winchester ’73 and Henry Fonda in Otto Preminger’s 1962 Advise and Consent. I spoke with Geer’s daughter, Ellen, about her father’s friendship with Guthrie, her memories of the singer, the Hollywood blacklist and the shrine that proves one man’s shack is another’s chateau. The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

TRUTHDIG: Tell us about the Shelter.

ELLEN GEER: It’s a museum that tells the story of the Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum. We named it “the Shelter” because it was a shelter in the early 1950s during the House Un-American Activities Committee, when my father and mother moved out here because their work was taken away from them in Hollywood. It became a haven not only for blacklisted actors, but for folk singers, people who were put aside in that very strict time. I was just a child, but my parents made a living selling fruits and vegetables. My father was a horticulturist who graduated from the University of Chicago with a major in botany. Not being able to act anymore, he began these wonderful gardens, Geer Gardens, here on the grounds in Topanga Canyon.

All of his kids learned the Latin names of the plants as best we could. If we were around when somebody drove in, we’d sell them. It was also during a time when we didn’t have city water. It was well water. We had lots of mountain lions, coyotes. We lived off of our chickens. It was a very poor time. Very hard. I don’t know how my family did it, actually, the guts that they had to create this space for artists to continue to work during that dark period of our country’s history.

Pop just wandered around and dug in the dirt. Later, when he got back to work again, he was grateful; he wasn’t angry. I learned: Don’t be bitter. It wasn’t anybody’s fault — except for HUAC and [Sen. Joe] McCarthy.

TD: When does Woody Guthrie enter the story of the Shelter?

GEER: Woody arrived at our door at the beginning of his Huntington’s chorea [the neurodegenerative disease]. My father and Woody were really good friends. They met each other at the end of the ’30s. They were very close, spent lots of time together. So, when Woody arrived in the 1950s, he became part of our space. He wasn’t playing as much anymore, but he wrote like crazy, so many songs here. And one can find them at the Woody Guthrie Foundation in New York City; I’m hoping one day we can have some of them out here, too.

TD: What are some of your personal memories of Woody?

GEER: I remember Woody very well. For somebody who was not even a teenager yet, he was somebody I’d sit back and look at. I think he had a thing for my older sister, so I was protecting her. [Laughs.] The folk songs and folk plays put on here were quite wonderful. In the 1950s, Woody met his wife Anneke at the Shelter. I think that’s a story I’ll never tell.

TD: When does the museum officially open?

GEER: Our grand opening is Aug. 3, when we’re having a big [Echoes in the Forest] Gala. My dad was a humanitarian — that’s why we decided to give a “humanitarian award,” instead of an actor’s award. Previous winners have included Congresswoman Maxine Waters and cinematographer Haskell Wexler. This year we’re giving the Will Geer Humanitarian Award to Woody at the gala. His grandson Damon is coming down and he’s going to sing. Arlo Guthrie and Pete Seeger have been here.

TD: What will be exhibited in the Shelter?

GEER: Pablo Capra of the Topanga Historical Society spent hours and hours in the backroom [of Ellen Geer’s Topanga home] where I have all these archives of my father’s life, and his work in theater and in labor camps: Newspapers, pictures, letters from Joan Crawford to Pop, all sorts of wonderful things the public should be able to see because it’s fascinating how art worked then — it’s so different now in the digital world. Many of the artifacts were found by Pablo, who took lots of photos of newspaper clippings [and also obtained materials at Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc., the Guthrie family archive]. Like when Pop got in trouble and Kate Hepburn had to bail him out. There are so many adventures of the life of being a liberal and caring about people.

The Library of Congress has asked for some of these documents, but I wanted to open the museum first, on the home ground where they happened in the ’50s. To me, it’s hallowed ground, for anybody to have gone through what happened in the early ’50s, and for us as a family to have succeeded in creating a space that continues the passion and education of the arts.

Other Shelter artifacts include a wonderful bust of Woody, that’s so like him. There’s a bust of my great-grandmother, Ella Reeve Bloor [a Mother Jones-like left-wing agitator and Communist Party central committee member from 1932-1948, whose autobiography inspired Guthrie’s 1913 Massacre]. There’s a [two-page typed] letter from Woody to the family in the 1940s. [Nearby is a replica of] the lyrics to This Land is Your Land handwritten on paper by Woody.

TD: Is This Land is Your Land a socialist song?

GEER: It’s a people’s song.

TD: When is the museum open and what is the price of admission?

GEER: It’s open around showtimes and admission is free.

TD: Do you know about Woody’s song about Donald Trump’s father?

GEER: Yes. We actually sang it at one of our Geer Family and Friends biannual events about Woody. The story starts at [Guthrie’s] birth in Oklahoma, his hard times, what it was like for him as a human being, the things he went through in his life, the reason he became a wanderer, a hobo, to find out what was going on in the country. Why he lived the life he lived, he had to express it through his songs.

Because Woody lived in New York City, he wrote Old Man Trump. It just puts down the way Fred Trump treated people as a landlord. Now Donald wants to be a landlord of the country, and I don’t think we should allow it.

TD: Your father’s probably best known to the public as Grandpa Zeb on The Waltons. He became America’s archetypal grandfather during that long-running 1970s TV series. What kind of a dad was he offscreen?

GEER: Well, my favorite thing was to go to a nursery with him, because he’d talk to the plants. He was so supportive. He wasn’t like your regular father. He didn’t have rules. He was a wonderful man, a very good man.

TD: What role did your father play in the 1954 pro-union, pro-Latino, feminist movie Salt of the Earth?

GEER: Pop went to New Mexico to play the sheriff. It was one of the most remarkable experiences of his life. They had to work so hard to get this film about working-class people being taken advantage of by the mine owners. I was just 10 years old then, and they couldn’t finish the film; they finished some of it up here, and I remember hanging clothes on a clothesline as a kid. That was my first film experience.

On Oct. 11, we’re presenting a 70th anniversary commemoration of Salt of the Earth at the Theatricum. We’ll show this remarkable film and have a panel you’ll moderate with myself; Becca Wilson, daughter of Salt’s screenwriter Michael Wilson; Bill Jarrico, son of producer Paul Jarrico; and, hopefully, Eva Bodenstedt, niece of Mexican co-star Rosaura Revueltas. United Farm Workers co-founder Dolores Huerta has also been invited to participate. Before the screening, I’ll read portions of my father’s remarkable 1951 testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Some of his remarks are very funny.

TD: Did Will become an informer and give HUAC names of other suspected progressives to save himself, like witnesses such as Elia Kazan did?

GEER: No, no. He’d always say, “Nobody knows how they’re going to react when they’re pinned like that.” He knew he wasn’t going to speak against his friends; he took the Fifth Amendment. Pete Seeger took the First and Lillian Hellman did it by a letter to HUAC, writing: “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.”

Years later, when I was 17, I tried out for Splendor in the Grass before Kazan. He got bright red in the face and asked, “How are your mother and father?” It was so weird; I never did read. When I got back, Pop was there with Morris Carnovsky [who Kazan had informed on to HUAC], and he asked who I read for. When I said, “Kazan,” he really freaked out.

TD: What gives you hope now?

GEER: It’s the Poor People’s Campaign that’s exciting me today. That’s what’s going to rise up again. The people unable to enjoy the wealth that can be had in this country; We have to get back to the common man having more rights.

For more information, visit theatricum.com/echoes-in-the-forest-annual-gala/

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.