Exposing the Realities of U.S.-Cuban Relations (Video & Transcript)

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer sits down with Jeri Rice, whose latest documentary "Embargo" explores U.S.-Cuba relations.

In this edition of “Live at Truthdig,” director and producer Jeri Rice sits down with Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer and Truthdig communications coordinator Sarah Wesley to discuss Rice’s latest documentary, “>Embargo.” The film looks at the decades-long relationship between the United States and Cuba and features interviews with Robert Kennedy Jr. and Sergei Khrushchev, son of former Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

Rice begins by describing her first meeting with Fidel Castro. “I found him to be extremely humble,” she says. This prompts Scheer to share his own meeting with Castro.

“It was a fascinating conversation because it was a reminder that Fidel didn’t have to be an enemy of the United States … this whole animosity with the United States didn’t have to happen,” Scheer says. “The strength of this movie is that our director here keeps raising this question: Why did this happen? Why the animosity?”

The three go on to discuss parallels between U.S.-Cuba relations and U.S. foreign policy with North Korea today. Rice says today’s tensions show how “we have rolled back on history … we haven’t come further.”

Scheer and Rice agree that the U.S. embargo, which the film notes is called a “blockade” by Cubans, didn’t work.

“Isolation breeds discontent,” Scheer states.

Rice says that, ultimately, she hopes the documentary starts a conversation about U.S. policies in other countries and the way we view our history with Cuba. “This movie puts [history] in a very human context,” she says. “This is a movie about us.”

Watch the trailer for “Embargo” below:

“Embargo” has showings at the Laemmle in Pasadena, Calif. Find ticket information here.

Watch a clip from “Embargo” below:

We are also pleased to announce a Truthdig trip to Cuba in spring 2018. Scheer and experts on Cuba will help host the trip. Sign up to receive details about the trip here.

Watch the full discussion in the video above and read a full transcript below, and check out past episodes of “Live at Truthdig” here.

–Posted by Emma Niles.

Full transcript:

SW: Live at Truthdig. I’m your host, Sarah Wesley, and today we have a great guest. She is a first-time filmmaker of the new film, Embargo. And we’re going to get into all of what that means, and Cuba and Trump and how it relates to U.S. and Cuba relations today. Also joining us is our Editor-in-Chief, Robert Scheer. And he also comes with a wealth of knowledge and spoke with Fidel himself in the sixties–in the sixties?

RS: Yeah.

SW: Yeah, so ah, we’re going to get into all of that. So please make sure, if you have any questions or comments, make sure you leave a question below the video. We’ll try to get to you, and we’ll be monitoring all of your questions right here on Facebook. And of course, share the video with your friends. It’s really important to share this information that we’re going to have today for you. So let’s get right into it. Embargo. Jeri Rice, thank you so much for joining us today.

JR: Thank you so much for having me on your show. Thrilled to be here.

SW: Thank you! And so with Embargo, I did get the privilege to watch it, and what an incredible film. I didn’t know, you know, where the film was going to start off, because you start with the history of Cuba, and you take us through Kennedy and Eisenhower, and then you bring us to Trump. So I wanted to know, what inspired this film? Because you mention that it took you 14 years to finish it up. So what inspired it, originally?

JR: Well, I wasn’t a filmmaker originally. And I had gone to Cuba with the University of Washington and 40 women, and the second day that we were there, we were greeted by Fidel Castro. And we had a six-hour meeting with Fidel Castro, and at that time, you know, he was kind of coming to some realizations, I think, himself; it was in 2002. And he was trying to explain to us what he had tried to do. He said, “I tried to create a utopia, but I didn’t succeed, and I don’t have time to fix it.” And he continued to tell us what that utopia would look like, from how they grow the food to how they do everything–it was a whole circle that he came back to six hours later. And I was so impressed; I mean, as a child from the Cuban Missile Crisis and the assassination of Kennedy, to have had the opportunity in my lifetime to meet this man and come to terms what that meant to me as an American. Then I went home and I started reading a lot about it, and calling the authors of the books. And it just has evolved 14 years later into the film Embargo that just came out in Los Angeles and New York.

SW: Wow. You know, for me, I–[inaudible] obviously, and I just remember growing up and hearing the stories about Fidel Castro and the communist regime, and it was just bad, bad, bad. And so, for you, when you originally met Fidel Castro, did you have any, like, preconceived notions? Did you have an idea of what he would be like?

JR: I had no idea what he would be like. And only the idea that I had from the American propaganda, growing up in this society, you know. And when I met him, I found him to be completely different than the Fidel Castro we had seen on television. I found him to be extremely intelligent, very curious, humble, and it was really a tremendous experience for me as a human being to be able to spend time with that man.

SW: Wow. And Bob, so, you spoke with Fidel as well. Can you talk a little bit about your experience with Fidel, and what that was like? You know, your preconceived ideas of him before and after?

RS: Well, actually, I’d been in Cuba a number of times. And when I had my conversation with Fidel, it was really quite disappointing, because I had waited for a month for this appointment, and it happened at night; finally I said, the heck with this, it’s not going to happen. And I got a ticket to get out of there. And guys showed up with submachine guns at my hotel, and said oh, your interview is on; come with us. Didn’t even say it was an interview, so I didn’t know whether it was going to be unpleasant or what have you. And they took me from one house to another, that was part of his security. And it was the night the Russians, ah, Soviets had invaded Czechoslovakia, in 1968. And so you know, first thing, he was a real bummer, because he wouldn’t let me use tape recorders, said we’re going to have a conversation, and I said great. You know, I was the editor of Ramparts magazine, and I was in the business of doing journalism. But we ended up having, it was about 11 o’clock at night, and we ended up talking until about seven in the morning. And meanwhile they had moved my bags to the plane; they delayed the plane, so everyone on the plane was very angry with me. And it was a fascinating conversation, because it was a reminder that Fidel didn’t have to be the enemy of the United States; he was quite critical of the Soviets going into Czechoslovakia, even then, ‘68, even though he had developed a dependency on the Soviet Union then.

And you know, I’ve written a book with a guy named Maurice Zeitlin, he’s a professor, ended up being a professor at UCLA; very good book, published in the early sixties. And basically, our book had a theme that is echoed in this movie, Embargo, which I saw and which I have great respect for. And that was basically this whole animosity with the United States didn’t have to happen. And I think what is a strength of this movie is that this young lady here keeps asking these questions out of a kind of innocence. Why do we have an embargo? What’s the big threat of Cuba? And those are the questions that the sophisticated journalists in the media, and the politicians, never ask. There are a lot of regimes in the world you don’t like, there are a lot of ones have mixed records of how they deal with their people; the only question should really be, was Cuba ever a threat to the United States? And there was one moment it was a real threat, but that was because of a failure of our policy, and that’s the Cuban Missile Crisis. And we’re coming up next month on an anniversary of that.

But the whole tension with Cuba was–as the film, I think, has very good footage, records–Fidel Castro had a lot of support in the United States; he overthrew a mob-run administration in Nevada under Batista; there was great unpopularity. He was a child of the elite, a lawyer, and he had picked up the gun to challenge, and he was successful. And there was a lot of cheering, and support. And then his problems regarding the United States was that he then proceeded to nationalize the Cuban power company, he nationalized some of the sugar, large latifundias and so forth. And he had a vision of social democracy, of you know, Cuba getting control of its resources, getting rid of the mob, controlling the casinos–you know, changing the culture. I always argued that Castro came out of much more of a Catholic tradition, and that he was really offended by the degree of prostitution and gambling and corruption and this regime that was quite corrupt and violent. And the irony is, the only reason we had a break in this crazy embargo and isolation is that a new pope came in, and said hey, let’s make peace here; we have a largely Catholic population that has been cut off from the Church, in many ways. We have a guy who started out as a believer in the Church, Fidel Castro, and at the end of the day, the Obama administration made peace with Cuba largely through the intervention of the pope in Rome. And I think the strength of this movie is it basically, and our director here keeps raising the question–why did this happen? You know, why this animosity? And the fact is, it’s like our invasion of Iraq, it’s like our now threatening Iran, it’s like our troubles throughout the world: did you have to pick this fight? And it was a fight pursued by democrats and republicans, and it’s unfortunate that it happened, and created refugees and trauma, wasted a lot of resources, and trapped the Cuban people in an unreal situation of isolation. Which made it, actually, easier for the regime, but not easier for the people.

SW: And I would add to that point, because growing up, that’s not the narrative that I’ve been taught, and that’s why I appreciate this film. Because it shows us the perspective of the Cuban people, and you’ve really done a great job of humanizing Castro in the film. And I want to just refer to a quote in the film, because I think it speaks to your point, Bob. It says, “Cuba would be a different place if it didn’t feel threatened–if it didn’t feel that the most powerful nation in the history of civilization was trying to topple its government, and that it poses a national security threat.” And you know, when you speak of Iraq and Iran and some of these other countries that are being isolated by the positions and policies of the United States–

RS: And North Korea.

SW: –and I was going to lead to that, and I wanted to ask you, Jeri, if you see any sort of connection between U.S. relations with Cuba in the sixties and up until now in North Korea.

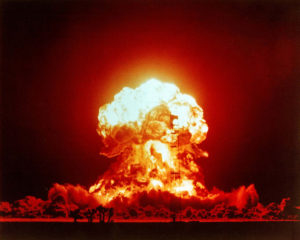

JR: We have rolled back on history. I mean, the movie ends–I hate to tell you the ending, but of course it ends with Marco Rubio and Donald Trump saying, “We hold the cards–we now hold the cards,” you know? And it also talks about how they don’t care if it’s another six months or six years, Cuba will be free–free of what? Back to Batista? I mean, you know, so there’s a real correlation going back to the 1960s, and also today we’re talking about a nuclear war. I mean, you know, President Trump was at the U.N. and talking about how, you know, what did he call the head of North Korea–Rocket Man.

SW: Rocket Man.

JR: Rocket Man. And you know, when we kind of push people into a corner–like we did with Castro. You know, we came to the brink of nuclear war in 1962, when I was a child; I was nine years old, and I will never forget that time. And it really, it really troubles me today to see that we haven’t come further. And then we had John Kennedy, and we had Nikita Khrushchev, who–they worked together to make sure that their generals didn’t basically blow us all up. And are we going to be as lucky this time?

RS: So it’s a timely movie. First of all, the irony here is if Trump were not president, and he was just tending to his hotel business and everything, he would see this as a great opportunity. He’d be all over, you know, the regime and everything, and trying to build more hotels and so forth–which, you know, is healthy. I mean, there’s something great about international trade and diplomacy; isolation breeds discontent, it’s perverse to isolate. This is what happened with North Korea. You know, you isolate a country, it gets stranger and stranger.

And in the case of Cuba, this was a population that had a natural affinity to the United States, people in America liked to go there, they loved the music, they loved the vibe, it’s a beautiful country. And when I went there the first time in the summer of 1960, I went on a lark. I was teaching at City College in New York, I saw a sign on the pole that says, “Get yourself to Cuba, for 25 bucks a week you can, or 25 bucks a day you can stay there”–I went down to Key West, got on a cheap air flight with my wife at the time, we went over there and ended up cutting sugar cane and having a ball. And again, I was asking, why is there tension–well, there wasn’t that much tension. Then a month later we put the first embargo. This was before the Bay of Pigs, you know. And I think it was for domestic political reasons. Basically, Cuba policy has been driven by either the interests of American investors in Cuba, the power company, the nickel compound…they didn’t want an example in Latin America of people taking control of their resources. That’s why they overthrew the government of Guatemala, before Castro; that’s why we were involved in Latin America, that’s why we’re attacking Venezuela now, with Trump’s speech; we don’t want to let these people make their own history, is the biggest problem. Castro had come to the United States, he was extremely popular, he stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, people were cheering him wildly and everything, and they didn’t want that model. And then for domestic purposes, particularly when you started having refugees and people leaving Cuba because their houses were taken, their sugar cane land was taken.

OK, of politicians Rubio is a very good example. They’re down there in Florida where people are saying, well, we’ll go with this, rah, rah, rah. Same thing that happened with China, by the way; that’s why we had this whole policy, we wouldn’t let communist China in the U.N., because we had refugees from China –it was like, no, they’re bad, bad, bad. Well, the fact is, and you know, there’s an irony in Trump’s speech, OK? And the first–people have to have sovereignty all over the world, they have to make their own–he says that, in his speech–amazing contradiction. However, if for some reason they’re inconvenient to us, we’ll go and blow them off the face of the Earth. That’s the contradiction. They should–we don’t want to impose our religion, we don’t want to impose our values, blah, blah–however, there’s this one, this one and that one, we’re going to blow them up because they bother us, you know. And the Cuba policy was always, always–and I think this movie, Embargo, makes it very clear–was always a frivolous and irrational activity. You know? And you were scared because the propaganda around it made it sound like wow, the fate of the world, life and death and everything, but it was always–and there’s one more thing the movie stresses, and that is well documented. Our government, under democrats and republicans, including good old John Kennedy, engaged in plots to assassinate Castro. Terrorism. And we blew up things in Cuba, and we supported people who–and we were dealing with, you know, Trafficante and these other gangsters that were, to do hits and everything. So we did a lot of terrorism against Cuba. And it was done, as I say, by American, democratic and republican presidents.

SW: Yeah–

RS: And the movie is a very good, they collected a lot of the documentary footage in this film, and it’s worth seeing just to get that impression, and many other reasons to watch the movie, which I think is quite thoughtful. And I hope it builds a good audience.

SW: And Jeri, you mentioned you have 300 hours worth of footage. So kind of scaling that down to this film, what was the intended message? Because you really could have gone in so many different directions.

JR: And I did, so many different times. [Laughter] But I think ultimately, I came down to the message. What I think is pretty unique about the movie is that I was able to capture interviews from Bobby Kennedy Jr. and Sergei Khrushchev, and how they talk to each other about the letters that Bobby’s uncle and Sergei’s father sent back and forth, and how they were smuggled in through a Russian spy, a Soviet spy, and how that really gave them the ability to communicate with each other separate and apart from their governments, which for all of us became, you know, life or death literally. And you know, we have the head of the Gambino family’s side, Albert Anastasia’s and Jack O’Halloran; Lucy Arnaz–

SW: Yes–

JR: –talking about her father, which I think is really interesting. Because it didn’t start in ‘59. Her father was almost murdered in 1933 when Batista did a military coup in the country, and he had to flee to the United States. And that’s how he came to love Lucy. You know, and so that’s a really interesting story. And I mean, so many stories and backgrounds in the movie, like Colin Powell’s chief of staff, and Colonel Wilkerson, who was so poignant in the movie, and Tony Zamora, who was a Bay of Pigs survivor who became the corporate counsel to the most right-wing organization, the Cuban-American Foundation, and yet goes back to Cuba later, and we had an incredible interview. And he was very emotional talking about his time going back to Cuba and what that meant. And I think that, you know, for me it’s a very human story. You know, we all hear about history, but we’re separate and apart from it. And this movie puts it in a very human context, where we see Ed Sullivan greeting Fidel, coming down the mountains and telling him he’s a hero. And then we see Ed Sullivan later, talking to Desi Arnaz about when he came. And you know it’s Americana. This is a movie about us.

SW: Wow. And so I also want to know, because this is our first–

RS: Can I just make one point?

SW: Yeah, sure!

RS: Just to make it contemporary. We’re now, I did an interview with William Perry, who had been Secretary of Defense in Clinton. He said, this is the most dangerous moment in terms of nuclear confrontation, with North Korea and so forth. So as another example, you’ve got a small country and suddenly they’re going to get a nuclear weapon–that was what the story was with the missile crisis. And you know, however these things get going, they have a life of their own. Misunderstanding, you know? It could be by accident, it could be just stupidity or what have you; it doesn’t mean you won’t have destruction of all human life on the planet as a result, as a consequence, OK? You get it wrong, and boom, you know? Donald Trump is awakened at three o’clock in the morning; some missiles have been fired; he rubs the sleep out of his eyes, and he’s got 12 minutes to 15 minutes to decide, do we blow them all up or not. OK? And then that’s the end–

SW: That’s scary.

RS: –irradiated cockroaches are surviving. So the real issue in this movie is, do you have adults watching the store? Is this policy serious? And this great director here, I think it’s a really good movie, takes us on this journey. And at first it bothered me, OK? She said, I don’t know anything about this, I happened to be on this trip, and I’m there, and so forth. And then, over 14 years I guess it took, she says hey–wait a minute, what’s going on, what’s it all about? And the fact is, you know, otherwise smart people say dumb things about what it’s all about. Oh–there’s a threat, or so forth. And then you have a few people, as you point out Bobby Kennedy’s son, nephew Jack Kennedy, and Khrushchev’s son, say it shouldn’t have happened. And in fact, our parents, our uncle knew it shouldn’t happen. And that scene–remember, the missile crisis is the closest we’ve come to the destruction of all life on this planet. And basically, we were saved because Khrushchev and Kennedy managed to find a way of communicating through the Russian embassy in Washington and saying, hey wait a minute, do we really want to go there? You know, this is where the ships are being turned back, the weapons are already there, and all it would have taken is the firing of one weapon by some drunken person on duty, or some irrational person–boom, it’s gone. There was life on this planet. Out.

SW: Right. So I do want to go to a reader question we have from Lavada Luening. Sorry if I mispronounced your name. So here’s a question to Jerry: What about the CIA? Are you aware they are bringing in heroin from Afghanistan? Did you know our troops are in Afghanistan guarding the poppy fields? American propaganda is coming out of the Middle East. What similarities do you see between Cuba and other countries who want off the petrodollar?

JR: Well, I can only speak to what the people in my film talked about. Because I’m not an expert’s expert like Bob is. But I will say that the CIA was definitely involved in this relationship that had started with Allen Dulles, and basically involved the Bush family and Richard Nixon. And that a lot of–I mean, it was for profit; it’s for their own profit. But the CIA has a tendency to be around the world, and what you see in this film, and the links to the CIA, I think you can expound upon. You know, and the links that you find take you all over the world within the movie Embargo.

RS: You should mention, in the movie Embargo there’s an interview with a young Kennedy, or not so young anymore, Bobby’s son. But he recounts at his uncle’s, Jack Kennedy’s [inaudible],–after the CIA betrayed him with the Bay of Pigs; that’s where things really started going, you know, we decided to overthrow Castro, we had this army that had been trained and so forth, and done by the CIA–and President Jack Kennedy’s response was, he wanted to smash the CIA into a thousand pieces. And we know he was very upset, and in fact David Talbot in his book, The Devil’s Chessboard, has a whole theory about when Allen Dulles, who was head of the CIA, got pushed out by Jack Kennedy and ends up on the Warren Commission and justifies somehow the assassination. But the argument, there is a theory, call it a conspiracy theory or anything you want, but we still don’t know exactly what happened with the death of Jack Kennedy. But we do know people like Allen Dulles were quite upset with Jack Kennedy and the CIA, and in David Talbot’s book he makes connections that are really quite uncomfortable between the CIA displeasure and the killing of Jack Kennedy. It is something to investigate. But there’s no question that Jack Kennedy was very disappointed with the CIA and did change the leadership there.

JR: One thing I’d like to add to that in the film that I think is really interesting, and Peter Kornbluh from the National Security Archives talks about it, that there was actually a plot, a declassified document, that they were going to kill Castro with a poison pen on the very day that Jack Kennedy was assassinated. So the links between the two assassinations, or the attempts, are clearly declassified in that one document.

SW: Wow. And you know, especially in this generation that we have coming up with this access to so much information online, on the Internet, and just we have access to so many historical documents now at our fingertips. And what I like about this film is that you’ve created this environment for us to go in and take out the things that we need in order to do more research on them. And that’s, like, one of the beautiful things about your film. And so as a first-time filmmaker, I want to switch gears a little bit, what was the most challenging thing about tackling such a complex topic?

JR: Not giving up. Because I thought the film was done in 2011, but it wasn’t. I thought it was done in 2012, and it wasn’t; 14, 15, 16. And today, I think we’ve kind of come to a close of this chapter and the beginning of another one.

RS: How do people see it, by the way?

JR: Well, we just showed it in Los Angeles for a week, and we premiered it in New York for a week, and we’re going to be showing it at the Pasadena Laemmle Theater on the 21st and the 22nd [of October], and we’re in plans now on how to roll it out across the country. So it’s, you know, it’s been baby steps and not giving up and getting the message out–

RS: Are you going to give us something for Truthdig?

JR: Oh, I’d give you whatever you want for Truthdig! [Laughter]

RS: All right, no, ‘cause we’d like to at least show a good trailer and give something to–

JR: Yeah, we gave you a trailer and I gave you a little clip that is some of the art from this beautiful artist on the island, and George Perez, who is one of my executive producers, talking about, you know, really the embargo and what that means. But you know, I’m happy to give you more.

RS: You know, we should mention, this use of embargo–which is so easy to do; now Donald Trump wants to increase the embargo, you know–well, Congress has done it on Russia; on Iran, he wants to tear up the agreements. So it just sounds like magic–oh, let’s have an embargo, let’s trap them in. The fact that–I think this film captures this as effectively as anything I’ve seen–that what an embargo does is makes whatever that initial situation far worse. It cuts people off. Like right now, if you have had, under Obama–OK, we had an easing of travel to Cuba, all right? Well, that increases the freedom of the Cuban people. They get to talk to people coming from Florida, get to see their relatives; they get to hear a different view of the United States, they get to see products they don’t have. You know, we’ve had the development of people having hotels, or bed and breakfasts in Cuba; they’re empowered to be entrepreneurs. So you have this very positive effect of cutting, you know, increasing ties with the United States; it happened with the rest of the world before. And now Donald Trump wants to reverse that, you know, and put up walls everywhere, including walls around Cuba. But then you have to ask yourself, why do you want to do that? If you really care about the freedom of the Cuban people, why don’t you want to let them talk to their relatives? Why don’t you let them talk to tourists, ordinary people? Be on the beaches, talk to them, so forth, stay in their homes, eat in the little restaurants that they’re setting up outside. If you really care about the freedom of the Cuban people–and that’s the question this film begs. It says, if you really care about–why would they be doing this? Why would you want to have an embargo, why would you want to–it certainly hasn’t worked. We’re talking about something that started in 1960, OK? Do the math. It hasn’t worked.

SW: And I like in the film that you show kind of the juxtaposition, because the Americans call it an embargo, but the Cubans call it a blockade.

JR: Because it’s bigger than an embargo. It doesn’t just include the United States, it includes the rest of the world. And right now, on November 1st the United Nations is going to meet again, and the United Nations vote usually is like 184 to 2. Last year we abstained, and so did Israel I believe, but this year I think Israel and the United States will be voting to hold the embargo again, and–

RS: So what’s with Israel? [Laughter] No, really, I was thinking about it just the other day. I don’t mean to bring up a whole different subject, but it’s kind of infuriating. There was Netanyahu, who said “Donald Trump gave the best speech I heard in 30 years of going to UN meetings,” and so forth, you know. And then on that particular thing, because there’s an irony in this; at the time of, I think it was the Six-Day War or even earlier, actually Castro made some comments that were favorable to Israel. This has been a complex history–yes–

JR: Israel–Israel came and helped them during the Special Period, and taught them how to grow the plants. I mean, you know, Israel was very helpful–

RS: When aid was cut off from the Soviet–

JR: –when the Soviet Union collapsed. Israel was very supportive of Cuba. And I think they still do business today, regardless of this–

RS: –yeah, it’s a complex relationship, but.

SW: Wow. So, just to wrap up a little bit, 14 years in the making and it’s finally here. So, congratulations!

JR: Thank you, thank you. Well, we’re not here yet; we have to get the message out. We really want to get this film out to the public. And you know, this is–I’m truly and independent filmmaker, and I’ve been very fortunate to meet Suzanne Thompson, who’s here with us today. And the Arts and Cultural Bridge Foundation, which has allowed us to get some legs.

RS: By the way, you say–I asked you where I can see it, I happened to be in New York a few days ago and I saw it in Greenwich Village–

JR: It was in, we showed–we had the most amazing screening in New York for a week, and at our opening we had a Q&A–like we had a Q&A, and you were kind enough to participate in–we had the Cuban ambassador to the United Nations there, we had Maggie Alarcón who was President Alarcón’s daughter, we had Sandra Levinson there from the Center for Cuban Studies, and Peter Kornbluh from the National Security Archive’s’ Cuba Project at George Washington University. And so we had a great panel, great discussion, and if there’s one thing I’d like this film to do, is to open up a new conversation. We need to look at this, we need to be active, because our lives, our children’s lives, our grandchildren’s lives, your future, it’s all at stake.

SW: Wow. I think that’s–

RS: You know, I just want to end on one note. It’s a cautionary tale. Because we actually are in a situation now where we have a president who thinks bullying other countries, particularly smaller ones, works. Or cutting them off, or building walls, or so forth. As opposed to using diplomacy, trade, all the things that even George Washington talked about, you know, in his farewell address–”gentle means,” you know. Yes, have tourism, have trade, and so forth. And so this film is a very good cautionary tale; we went down the road of belligerence and bullying and walls with Cuba, and it didn’t work. And it hurt the Cuban people most of all. OK? And if you want to turn people into refugees, you want to have chaos, you do more of that, you know? I’m very sympathetic to the people who try to leave Cuba and then they have to take rickety boats and so forth; that’s not a good human rights solution. Why wouldn’t you make it easier to have normal travel, normal trade? Going both ways. And then the people of Cuba can vote with their feet; they want to go try to live in Miami or visit their relatives or apply for citizenship–OK. Let them do it. And if you care so much about their freedom, you can give them a pass to enter the country.

SW: Right. And that sounds like a plausible thing to do. Like, at the end of your film you kind of like–it feels like a call to action after you kind of close with Donald Trump’s remarks about Cuba and what he intends to do and what he has done.

JR: And the Star-Spangled Banner. They took over our country–I mean, that’s the message; we need to take it back. And there’s one more thing I’d like to say, because it’s interesting. Donald Trump’s business partner, George Perez, is in the movie. He’s the executive producer. And he was the man that they called up, that Donald Trump called up to build the wall. And he said you know, I was born in Argentina, my parents were Cuban, and I grew up in Colombia; what side would I be on? And I think that became a riff. But if there’s one thing I could say to President Trump, you should probably call your friend George Perez for some counseling on this, on the diplomatic relations before you really go in the UN and do exactly what you’re doing.

SW: Well, you heard it here first, Trump. [Laughter] OK, so we’re going to wrap up. But I do want to mention that if you are interested in Cuba, Truthdig is hosting a trip to Cuba in the spring of 2018. We’re solidifying the dates, and it’s going to be hosted by our Editor-in-Chief, our wonderful Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer. So please be on the lookout, we’re going to have a link on our website about it where you can get more information.

RS: Spring Break Havana.

SW: Spring Break Havana with ramen, cigars, and politics. So let’s wrap up there. Thank you so much, Jeri, for joining us today–

JR: Thank you.

SW: –and for allowing us to speak about your film and broadcast it. And Bob, it’s always a pleasure with you here as well. So thank you. And if you liked the video, please share it with your friends; the link is right below. Also please comment, we’re going to have this posted on the site in just a few. And then we’re going to have more information about our trip to Cuba in spring. Catch you next week.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.